Google “top 25 greatest screenwriters of all time” and you’ll find every single one of them is a man. But from 1915 into the 1930s, a woman named Frances Marion was the most successful and highest-paid screenwriter in show biz.

A California girl, Marion Benson Owens was born in 1888. The high point of her early education was expulsion from school at age 12 for drawing snarky cartoons of her teachers — a badge she wore with pride because she felt it set her apart from fellow classmates she considered just plain ordinary.

Tales of high-sea adventure

Stuck at home with private tutors, Owens grew close to an aunt and uncle who lived with the family, and to whom she credited her vivid imagination and storytelling talents. Her aunt held mock séances while young Marion voiced long-dead relatives. Her uncle, an old salt, took her to the bars up and down San Francisco’s fabled Barbary Coast where she heard — and kept a diary of — tales of ocean voyages and high-seas adventure. It was on those pages, carefully hidden under her mattress, that she honed her writing skills. At age 16, perhaps drawing on the budding talent that got her bounced out of school four years earlier, Marion Owens enrolled in San Francisco’s Mark Hopkins Art Institute, one of America’s oldest schools for contemporary art education.

But Owens’ life was turned upside down two years later when her family lost everything in the San Francisco earthquake of 1906. The art institute was gone; her father’s business was no more; and Owens’ dreams of attending the eastern college she had dreamed of went up in smoke. Discouraged, and with no immediate prospects, she married her art instructor. When the marriage eventually ended in divorce, Owens decided to strike out on her own.

Name change

A seeming Jill of all trades, mistress of none, Marion Owens skipped from job to job. She worked as a commercial artist for Western Pacific Railroads and painted movie posters for nearby theaters. Local magazines published her poems and short stories. A brief stint as a reporter and illustrator with the San Francisco Examiner led to her first encounters with Hollywood that would kick-start her prolific career. Her good looks brought her work as a photographer’s model, followed by some small acting roles and a new stage name — Frances Marion.

But Marion wanted to do more than just act in the movies; she wanted to write them. It was during this period she met Lois Weber, a successful female filmmaker at a small studio. But Weber insisted on hiring Marion as an actress, promising to teach her everything she needed to one day work behind the camera. And so it was that Frances Marion learned every aspect of the trade — from writing press releases to painting sets to cutting and splicing film.

Work for free

In 1915, in pursuit of her dream, she took a huge gamble and headed east. At the time, New Jersey and New York claimed the title of motion-picture capital of America.

So Frances Marion wrote to several East Coast movie producers, making them an offer she hoped they couldn’t refuse: She would work for two weeks without pay on condition that, if her work proved satisfactory, they would hire her to a one-year contract at $200 per week — an outrageous salary at the time.

New York World Studios

The first producer she met promptly dismissed her because of her looks, telling her she should be “wearing beautiful furs and jewelry, not thinking about a lowly writing job.” But her audacious pitch caught the eye of William Brady, owner of New York City’s World Studios. With a soft spot for fellow San Franciscans, and intrigued by her checkered, diverse work history, Brady took a chance on the two-week trial, during which Marion wrote revisions for a film starring the producer’s daughter that earned the studio a $9,000 profit.

Suddenly touted as the “highest paid scenario writer in America” by the New York papers, Frances Marion got the contract and the $200 weekly salary she demanded, no questions asked. Within six months, she was promoted to head the scenario department at World Studios where, in addition to writing her own films, she reviewed all the scripts that came into the studio, helped cast films, supervised screen tests, and directed scenes.

Paired with Mary Pickford

By 1917, after more than a year at World Studios, and with 50 films under her belt, Marion was lured back to California and the Famous Players-Lasky Corporation, whose most famous player was Mary Pickford, the original “It Girl with the Golden Curls.” She would be paid $50,000 a year writing films for Pickford that showcased her strengths and provided a variety of roles.

But as America’s involvement in World War I became inevitable, Marion wanted to use her writing skills to serve her country. In 1918 she gave up her hefty salary at Famous Players-Lasky Corporation to volunteer with the military.

World War I volunteer

The Committee of Public Information, a wartime government agency, sent her to Paris with the American troops. In her role filming the work of Allied women working overseas, and documenting their contributions, Frances Marion became the first Allied woman and first war correspondent to cross the Rhine following the armistice in November of that year.

After the war, she returned to California where, by the 1920s, she was working for MGM, earning $3,000/week — the equivalent today of just over $39,000. It was the Golden Age of Hollywood. Silent movies were all the rage, their stars idolized the world over. It was also a time when women could make names for themselves through the stories they imagined for the silent screen; in fact, more than half of all silent films are now thought to have been penned by women. And these trailblazing women benefited from their friendships in the new industry, Frances Marion included. Her life and career changed dramatically when she became fast friends with Mary Pickford, who insisted on hiring Marion as her exclusive screenwriter.

130 films

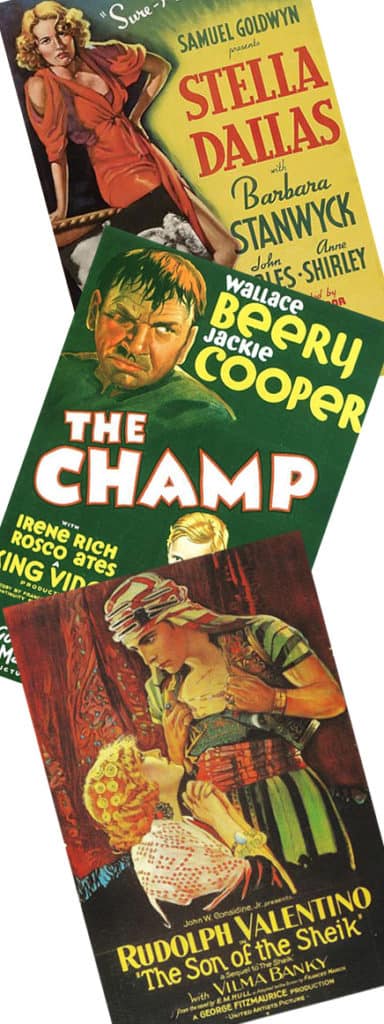

With over 300 scripts and 130 produced films to her name, Frances Marion’s career took her from silent films into talking pictures. Her credits include the tearjerker, Stella Dallas, (1925) and Rudolph Valentino’s final film, Son of the Sheik (1926). She oversaw Greta Garbo’s debut in talkies in Anna Christie — the highest-grossing film of 1930, and revived the on-life-support career of Marie Dressler that same year by pairing her with Wallace Beery in Min and Bill, earning Dressler the Academy Award.

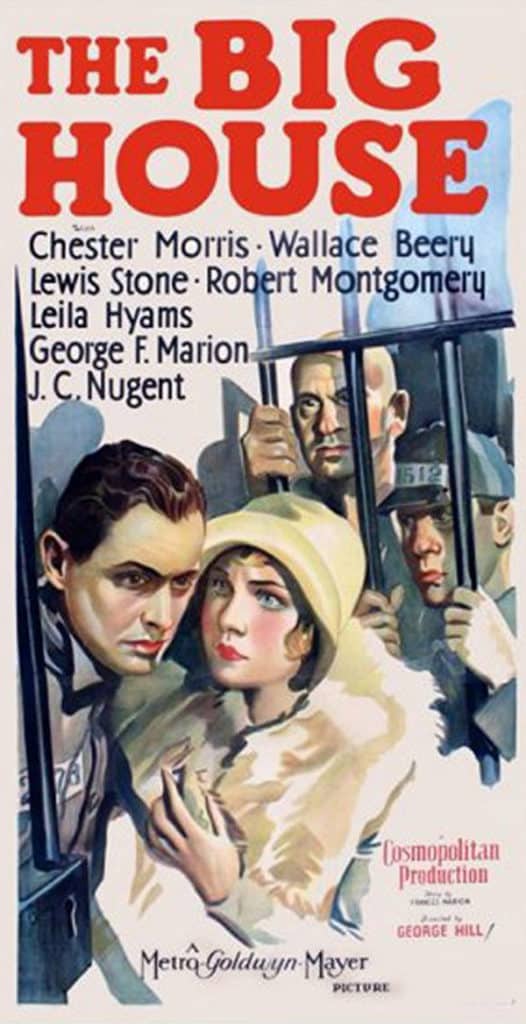

She won an Oscar for her screenplay of The Big House, with its “savagely realistic” depiction of prison life, in 1930 and, the next year, became the first person to win two Academy Awards — this time for The Champ, with Wallace Beery and a very young Jackie Cooper.

Walking away from Hollywood

Then, in 1946, after a lucrative career and four marriages, Frances Marion simply walked away from Hollywood. She became disillusioned as she watched it shift from an artistic, creative business to a purely commercial pursuit. She felt her creative control slipping away and grew frustrated with new production and censorship guidelines applied to the major studios — women’s legs could not be shown above the knee; married couples could not be seen in a double bed; love scenes could carry no suggestion of sex — that forced her to write what she considered simplistic, infantile stories.

As a result, the woman who literally wrote the first textbook on Hollywood screenwriting in 1937 — How to Write and Sell Film Stories — and taught screenwriting at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, is all but unknown, with most of her films now lost to time.

Little known buy highly influential

But Frances Marion helped shape Hollywood’s Golden Age as one of Hollywood’s most influential and successful screenwriters. As a founding member of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences and a force in establishing what eventually became the Screenwriter’s Guild, in 1972 the City of Los Angeles named her the “dean of Hollywood screenwriters.” It was there, a year later, at age 85, that Frances Marion died of a ruptured aneurysm. Her ashes were scattered over Aetna Springs, a resort that was once one of California’s most popular mineral springs but, today, lies in ruins.

Francis Marion was indeed creative and influential. But Anita Loos and John Emerson should be credited for writing the first book on writing for films, How to Write Photoplays, published in 1920. That might have been missed since “Photoplays” as a term is no longer used. Anita Loos probably deserves her own section, and there were other women in that period as well, but Anita really should be mentioned in this article since she worked with Frances in New York and had a similar influence and successful career.