For two decades, Washington reporter Doris Fleeson took no prisoners as she stalked the halls of Congress in her white gloves and designer hats, exposing ignorance, fraud and hypocrisy wherever she found it. One of the best and most-respected reporters of her day, she struck fear in the hearts of Congressmen, press secretaries and presidents of both parties, one of whom, John F. Kennedy, quailed at the prospect of being “Fleesonized” by her sharp prose and what Newsweek called “the sharp edge of her typewriter.”

Journalism degree in 1923

Born in Kansas, the youngest of six, she graduated as Sterling High’s valedictorian in 1918. After spending a year at a private Christian college, she enrolled at the University of Kansas, earning her journalism degree in 1923. She cut her teeth at the Kansas Pittsburg Sun and the News-Index in Illinois before being hired as an editor at Great Neck News on Long Island, New York. But it wasn’t until 1927, when she joined the New York Daily News, considered the country’s first successful tabloid, that her career took off.

Birth of a Tabloid Reporter

As a general assignment reporter, Fleeson covered the juicy stuff — crimes, trials, scandals and investigations. It was there she perfected the art of hooking readers with the lede, or first sentence: “We belonged to the who-the-hell-reads-the-second-paragraph school…where we learned to hit ’em in the eye.”

She credited her tabloid training in tight deadlines for her ability to go from a press conference, debate or raucous convention floor to a typewriter — while other reporters were still looking at their notes, sorting out what had just happened, she could turn out 700 words of clean, sharp prose that cut to the chase. It was that crisp reporting that won her a plum assignment at the Daily News’ Albany bureau, where she got her first taste of the political reporting that would become her stock-in-trade, covering then-New York Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt.

From Washington to the Front Lines

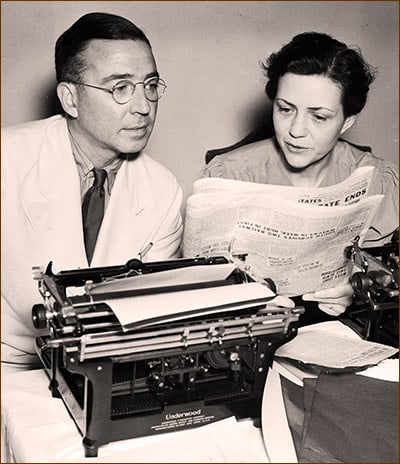

In 1930 she married fellow Daily News reporter John O’Donnell. The couple moved to Washington, DC, where both worked at the paper’s Washington Bureau, co-writing a political column called “Capitol Stuff.”

The only permanent female member of the press corps accompanying President Roosevelt on his campaign tours (1932, 1936 and 1940), she was a fierce New Dealer whose views were diametrically opposed to those of her husband — so much so that the couple divorced and their column ended in 1942. But it was the ’40s — a time when newsrooms were toxic environments for women. So while O’Donnell kept his job as the paper’s Washington correspondent, Fleeson was shipped back to the New York office to write radio news.

That lasted for just a year before she left the Daily News for Woman’s Home Companion in 1943. A highly successful monthly journal, its contributors included Rachel Carson, John Steinbeck, Willa Cather and P. G. Wodehouse. During the war years, it ran editorials for female doctors in the military and an investigation of rationing fraud — right up Fleeson’s alley. But she was hired as a roving war correspondent who, in a series of 10 articles, covered the front lines from the beaches of Normandy to the landings in World War II.

First Syndicated Female Political Columnist

When the war ended in 1945, Doris Fleeson returned to Washington, DC. At the urging of good friend H. L. Mencken, nationally-known writer, editor and critic, and a keen observer of American life and culture, she launched herself as a political columnist. At first, only two papers — the Boston Globe and Washington Evening Star — promised to print her copy. But as her client list grew, along with her reputation for covering tough beats and even tougher analysis, her column was eventually carried in over 100 newspapers nationwide.

One of Fleeson’s 1946 columns became national front-page news when she aired some SCOTUS dirty laundry and exposed a nasty feud between two of the nation’s highest justices. Her scoops continued to pull in more subscribers to the column until she was writing five days a week for United Features Syndicate.

Feminist and Champion of the Underdog

Throughout her career — and in no small part because of it — Doris Fleeson was also a militant feminist and champion of the underdog. She knew only too well what having to submit to the sexist indignities of being a female reporter in the toxic male environment of 1940s and 1950s Washington was like. After all, she was routinely referred to as the “Capitol’s top news-hen” by non other than Newsweek magazine.

But quick as she was to neatly skewer the male politicians she covered, she was amazingly kind and generous to young female reporters. One of them, Mary McGrory of the Washington Star, who covered the McCarthy hearings in the ’50s, idolized Doris Fleeson, writing, “to be a woman reporter in the man’s world of Washington in the ’40s and ’50s was to be patronized or excluded. [Fleeson] knew that few of the men were her peers and none her superior, and she was, well in advance of the women’s liberation movement, a militant feminist.”

In 1933, she helped found the American Newspapers Guild, fighting for a minimum wage of $35/week for reporters. She led the charge to have women’s restrooms installed in Congressional galleries. A pioneer in helping Black reporters break color barriers, in 1953 she sponsored the first African American applicant for membership in the Women’s National Press Club, where she was a member. She had long been a foe of the National Press Club; strictly off-limits to female reporters and considered “one of the ugliest symbols of gender discrimination in the world of journalism,” it would not open its doors to women until 1971.

A Picture of Domesticity

In 1958, Fleeson married Dan Kimball, a World War II pilot who went on to become Truman’s Secretary of the Navy, their Washington wedding attended by luminaries like Eleanor Roosevelt, Bernard Baruch and Mrs. Fiorello LaGuardia. The couple settled into a happy 12-year marriage that ended with Kimball’s death on their anniversary in 1970.

To Kimball, the woman known as the scourge of statesmen and oily politicians was “my little bride.” And, in fact, she could be the very picture of domesticity. It wasn’t unusual to find her on a Sunday, as columnist Mary McGrory did on a visit to Fleeson’s Georgetown home, sewing a fresh white collar and cuffs on her favorite dark blue dress.

But looks could be deceiving. Author and Fleeson biographer Carolyn Saylor describes one occasion when Lady Bird Johnson complimented Fleeson: “What a gorgeous dress, Doris. It makes you look just like a sweet, old-fashioned girl.” To which the nearby wife of then-Senator Stuart Symington replied, “Yes, just a sweet old-fashioned girl with a shiv in her hand.”

Death and a Legacy

As tough and resilient as Doris Fleeson could be, the 1964 campaign of Lydon B. Johnson, proved to be her last when she collapsed on the campaign trail, suffering from circulatory disorders. Several years later, she went into semi-retirement, her twice-weekly columns distributed by United Features Syndicate, Inc., to 90 newspapers. And in 1970, having been incapacitated by a stroke a year earlier, she died at her Georgetown home at the age of 69 of massive thrombosis just 36 hours after her husband’s death on their 12th anniversary. They are buried together in Washington’s Arlington Cemetery.

Over the course of her 22-year career, she wrote 5,500 columns, covered five administrations, and never hesitated to scold, criticize and dispense unsolicited advice to politicians on both sides of the aisle. She was the recipient of the Raymond Clapper Award, given by the White House Correspondents Association to a journalist for distinguished Washington reporting and, on two occasions, honored by the New York Newspaperwoman’s Club for distinguished reporting.

But more importantly, Doris Fleeson redefined what it means to be a woman in today’s daily newspapers. She learned early on how to turn the sexism and chauvinism of America’s newsrooms to her advantage, sussing out stories and cultivating sources her male colleagues could not, simply by being female. And she was the only political reporter of her day, male or female, to approach the often-dry issues of national affairs like a no-nonsense police reporter who pulled no punches.

As columnist Mary McGrory once put it, “she headed for Capitol Hill, where she regularly called senators and congressmen off the floor — whether to be asked for information or be given a piece of her mind, they were never sure.” Which was exactly the way Doris Fleeson liked it.

When my mother was in the Navy during WWII, she had a stopover in Washington DC, and read Doris’s column for the first time. She immediately called home to tell her mother, Mary Fleeson Reynolds, that there was a columnist by the same surname as her own.

“Yes, I know,” said my grandmother, “she’s my first cousin!”

I have since connected our families on Ancestry, and I’ve read everything I can find about her. I’m proud to call her my cousin!