Philadelphia-born Anna Coleman Ladd is best known for her neoclassical portrait busts and bronze sculptures of sprites frolicking in public fountains. But her greatest work — and her most important legacy — was restoring the self-respect, honor and dignity to World War I veterans known by the French as “the men with the broken faces.”

2018 marked the end of the World War I Centenary (2014-2018). When we think of The Great War, images of gas masks, barbed wire, trenches and machine guns come to mind. First used on the battlefields of WWI, machine guns, with their rapid fire and long range, were positively deadly, killing or wounding roughly 60,000 British soldiers at the Battle of the Somme in just one day. But the trenches — long, deep ditches dug as protective defenses, also proved an unexpected enemy.

Trench wounds

Soldiers with no experience in trench warfare popped their heads above the trenches, thinking they could duck back quickly enough to avoid the hail of machine gun fire. Many were proven wrong, coming back down with a jaw, cheek, nose or an entire face missing.

Fans of HBO’s “Boardwalk Empire” will remember the character Richard Harrow. He was a disfigured WWI veteran whose injuries shattered the left side of his face. Until his last few scenes, we always saw Harrow wearing an expressionless tin mask molded to his face, painted to match his skin, and held in place with eyeglasses. Harrow’s character was based upon one of those “men with the broken faces” who may well have sought the help of Anna Coleman Ladd.

The daughter of well-to-do Bryn Mawr socialites, Anna Coleman Ladd was educated in Paris and Rome, where she studied neoclassical sculpture. At 26 she married a physician from Boston, where she continued her work, specializing in public art and portrait busts. But all that changed when her husband, Dr. Maynard Ladd, was appointed to a post as medical advisor to the American Red Cross at the French front lines. By then, Ladd had already made a name for herself as a successful artist.

‘Tin noses shop’

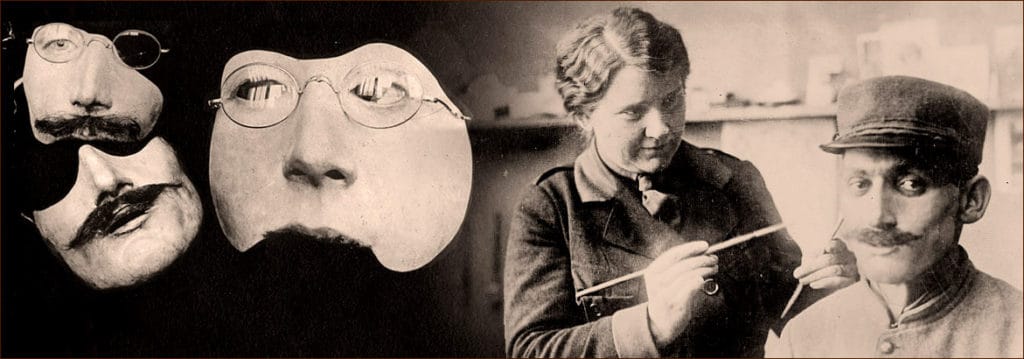

In late 1917, Anna Coleman Ladd met Francis Derwent Wood, a British sculptor and founder of the 3rd London General Hospital’s Masks for Facial Disfigurement Department. But soldiers knew it as the “Tin Noses Shop.” Wood’s department was for those patients whose faces remained so irreparably disfigured despite facial surgery they were deemed unsuitable for routine pre- and post-op photographs. After all, this was a time when the most advanced cosmetic surgical procedure was the repair of a cleft lip. While extensive surgery and complex skin grafts were options for some, many soldiers’ facial injuries far surpassed even the best surgeon’s ability. These men turned to prosthetic masks and the “Tin Noses Shop” run by Wood, whose goal as an artist was to restore, as best possible, a man’s face to its pre-war appearance.

With her skills and artistic training, Ladd, age 39 at the time and living in Paris, believed she could do the same for the men for whom masks were the last resort. She knew severe facial disfigurement condemned many veterans to a life of isolation unless their faces could be restored. In fact, Sidcup, England, home to a soldiers’ hospital, painted its public benches blue to warn townspeople that any man sitting on one would be distressing to view.

Horrified stares

Ladd made it her mission to fashion masks so those soldiers could once again appear in public without shocking and being subjected to the horrified stares of passersby.

After consulting with Wood, Anna Coleman Ladd opened her Studio for Portrait Masks in Paris. Funded and administered by the American Red Cross, it was a restful place where she and four assistants often worked for weeks to produce a single prosthetic mask. After a soldier had recuperated from his initial injury and what were often multiple surgeries to reconstruct his face, plaster casts were made of the face, from which clay or plasticine casts were then made that formed the basis of each mask. It wasn’t unusual for new patients making their way to Ladd’s Parisian studio to find themselves in rooms and hallways lined with row after row of plaster casts and masks in progress.

While some masks were full-face, most covered just those areas that were damaged — perhaps a chin and one cheek, or a nose and an eye. If the mask included a restoration of the patient’s mouth, Ladd modeled the lips open just enough to allow for a cigarette holder. And while most prosthetic masks were held in place with wire-rim eyeglasses, thin wire or ribbon could also be used. Because Ladd’s services were donated, the price of each mask was only about $18.

The mask itself was made of 1/32nd inch-thick copper — or, as one visitor to the studio noted, “the thinness of a calling card” — and weighed between 4-9 ounces. It was painstaking detailed and painted to match the soldier’s skin color, often while the man was wearing the mask, so the tone would work in sunny and cloudy weather, even capturing the bluish tinge of a man’s freshly-shaved cheeks. Eyebrows, lashes and mustaches were crafted of human hair or extremely fine metal strips.

Over the course of two years, Ladd’s studio produced 185 masks — a number that pales compared to World War I’s estimated 20,000 facial casualties. But by 1920, the American Red Cross could no longer fund her studio, and it closed despite each mask only lasting a few years. Ladd wrote of one of her first patients, “He had worn his mask constantly and was still wearing it in spite of the fact it was very battered and looked awful.”

French Legion of Honor

Anna Coleman Ladd left Paris and returned to America after the 1919 armistice. In 1932 she was made a Chevalier of the French Legion of Honor — the highest French decoration and among the most famous in the world. Though she continued to sculpt, her style reverted to her pre-war pieces with one difference. The war memorials and warrior figures she created inevitably featured sharp-jawed soldiers with perfect features some critics described as mask-like. She retired in 1936 and died in Santa Barbara, California, in 1939 at the age of 60.

Today, none of Ladd’s prosthetic masks are known to survive except a small cheek prosthesis included in a 2016 exhibition in England. Little more than a thin curve of skin, it fails to do justice to Ladd’s artistry and her legacy in restoring self-respect and honor to those World War I soldiers with the “broken faces,” as captured in one patient’s letter to her: “The woman I love no longer finds me repulsive, as she had the right to do. She has agreed to be my wife.”