A facilitator for runaway slaves traveling north on the underground railroad in the early 19th century, Henrietta Duterte also made local and national history in the business of burying the dead.

Since ancient times, women have been caregivers to the dead — washing the body; anointing it with sweet-smelling oils; shrouding or dressing it; and preparing the features in hopes the face might look “as pleasant as when in health.” But by the 1830s, death had become a profitable business. Men dominated America’s funeral parlors and mortuary services as women were sidelined, relegated to shaping mourning rituals and overseeing the fashion and etiquette of death. Philadelphia’s Henrietta Smith Bowers Duterte knocked all that on its head.

Philanthropist and abolitionist

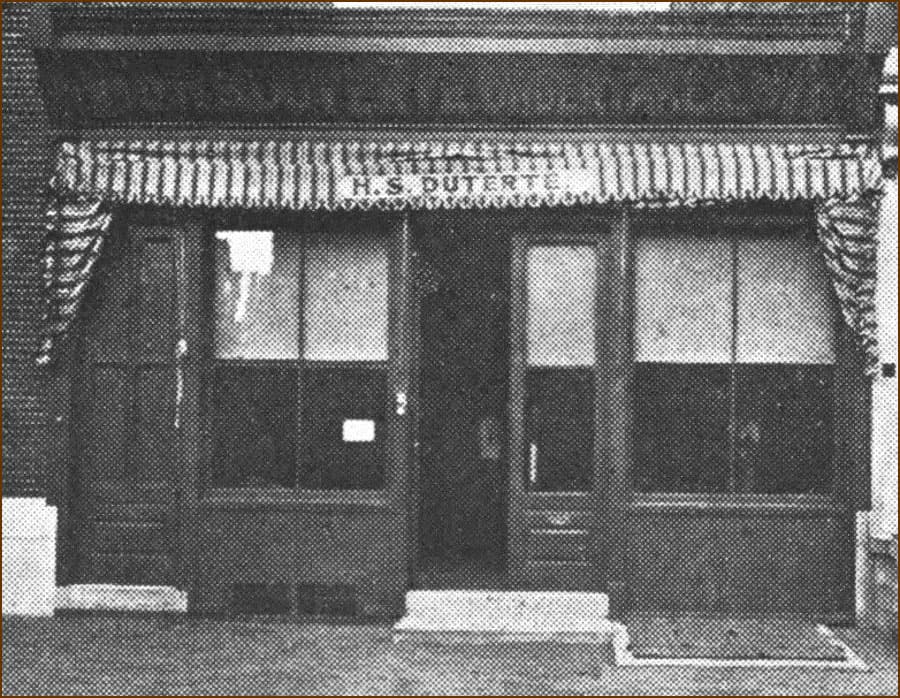

Henrietta Duterte (pronounced dew-tier) was more than America’s first African-American funeral home owner and the first American woman to own a mortuary. She was a philanthropist and abolitionist whose business at 838 Lombard Street in Philadelphia was a stop on the Underground Railroad.

One of 13 children born into a well-established free Black family who moved from Baltimore to Philadelphia around 1810, Duterte grew up in the city’s Seventh Ward, a place Philadelphia’s notable black families called home for almost two centuries. It was a community made famous by W.E.B. Dubois’ groundbreaking sociology study, The Philadelphia Negro, that chronicled the city’s elite black population.

Wife of a coffin maker

Always known for her fashionable capes, cloaks, hats and manner of dress, Henrietta Bowers made an early name for herself as an excellent tailor who catered to Philadelphia’s middle and upper classes. It wasn’t until 1852, at age 35, that she married Francis Duterte, a Haitian-born coffin maker. A member of the Moral Reform Society, known for its support of abolition and equal rights for all African Americans in the United States, he served as a secretary for the National Colored Convention of 1855, whose theme was economic and social liberty for free African Americans.

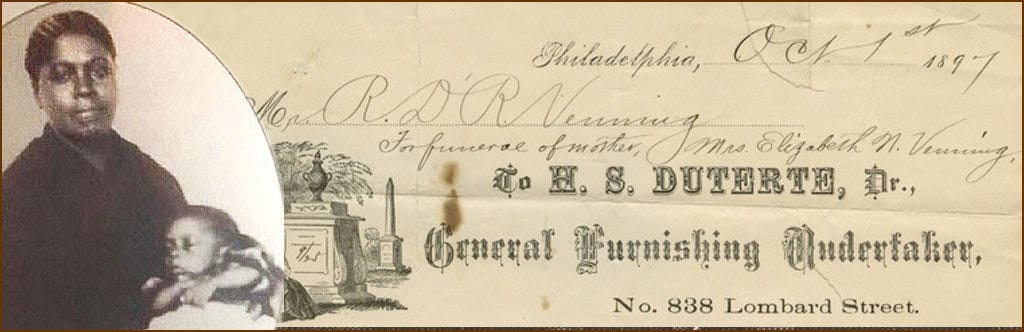

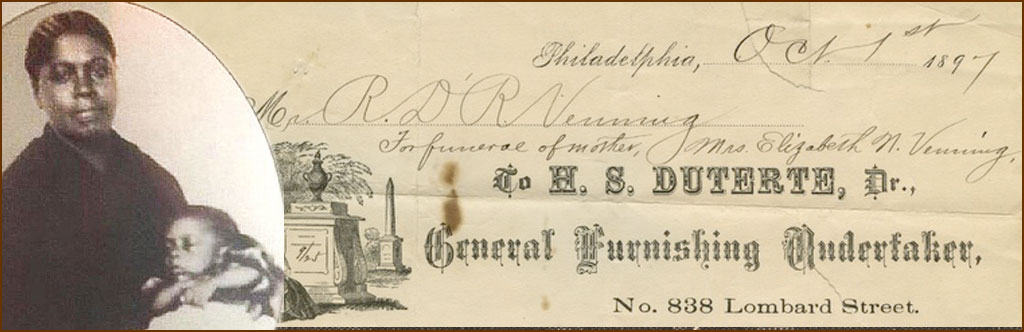

Although the couple had several children, none survived infancy. Today, only one known photo (above) of Duterte survives; in it she sits, dressed in black, cradling one of her children whose eyes are closed in sleep or, at a time when post-mortem photos had become treasured family keepsakes, perhaps in death.

After her husband’s sudden death in late 1859 at just 45 years of age, Duterte defied her era’s gender restrictions by assuming control of his business, becoming not just the first female undertaker in Philadelphia, but the first woman undertaker in America. Running the business in her own name, she earned a reputation for being prompt in conducting her business affairs, sympathetic, and accommodating to all—rich or poor, black or white. She was also known as being a fast undertaker — an asset at a time when embalming was still in its infancy.

One out of 63

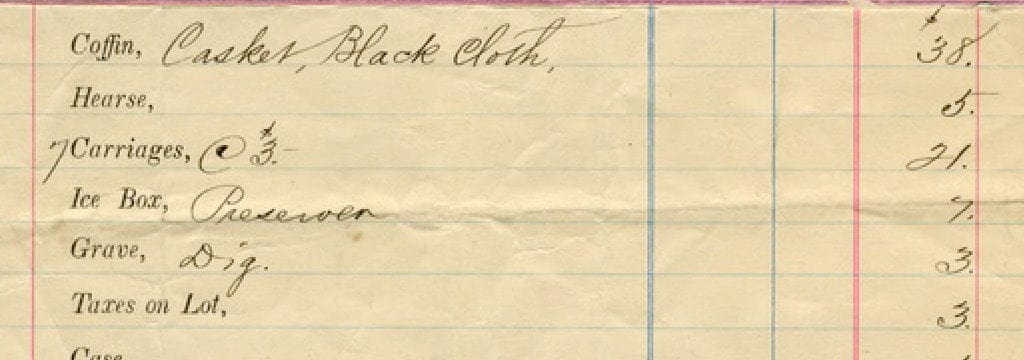

In 1860, a time when the rituals of death were no longer considered suitable for a woman’s delicate sensibilities, Duterte is the only female among McElroy’s Philadelphia City Directory listing of 63 professional undertakers. A surviving document in the collection of The Library Company of Philadelphia lists: “H.S. Duterte, Dr.; General Furnishing Undertaker, Address No. 838 Lombard Street.”

But Duterte used her mortuary business to do more than prepare and bury the dead. As an agent of the Underground Railroad, she was perfectly positioned to hide runaways in coffins or disguise them as members of funeral processions, thereby ensuring their safe passage through the city. This was a time when Philadelphia was known as the final destination for some of the most daring and inventive escapes of slaves from Maryland, Delaware and Virginia. Ten years before her husband’s death, Henry “Box” Brown had shipped himself in a wooden box from Virginia to abolitionists in the City of Brotherly Love. And 1848 saw the arrival of Ellen and William Craft from Georgia. Ellen, an enslaved woman of mixed race, passed herself off as a wealthy young white male plantation owner traveling with his slave — William.

Funded community organizations

As well as using her position to help fugitive slaves on their way to freedom, Duterte generously supported Philadelphia’s African American community through her philanthropy. She raised necessary funds to pay the pastor’s salary at the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas (founded in 1792, it was the first African American Episcopal Church in the nation), and helped fund Stephen Smith’s Philadelphia Home for Aged and Infirm Colored Persons.

Duterte died in Philadelphia in 1903 at the age of 83. She had lived to see her mortuary become one of Philadelphia’s most successful African American businesses, taking in roughly $8,000/year (equivalent to $199,211 in 2018). She left an estate that included the mortuary, hearses, carriages, burial lots in four cemeteries, and homes. Her nephew, Joseph Seth, continued to operate the business until his own death in 1927.

She is buried in historic Eden Cemetery in Collingdale, Pennsylvania. Eden was created in 1902 as the final resting place for African Americans buried in abandoned cemeteries, potter’s fields and churchyards throughout Philadelphia after two formally recognized African-American cemeteries (Lebanon and Olive) fell into disrepair and were condemned, forcing all the graves to be uncovered and re-interred at Eden. Among those who lie beneath Eden’s soil are Philadelphia civil rights activist Octavius Catto, opera singer Marian Anderson and William Still, Father of the Underground Railroad.

I had never seen or heard of this historic woman. Thank you for introducing me to her story. Our story.

Is there a book on Henrietta Duterte?

ANSWER: None that we’re aware of.