Being a historic foodways researcher, I think of Amelia Simmons, Hannah Glasse, Eliza Leslie and Mary Randolph as old friends. It took chef and culinary historian Michael Twitty’s book, The Cooking Gene, to introduce me to Malinda Russell. Far more than just a collection of recipes, Russell’s slim volume sheds light on the history, culture and power structure of her time.

Early Life

For years, historians and culinary researchers have been frustrated by the dearth of information about Malinda Russell’s early life. All we know is contained in the few details she chose to include in the preface of her book under “A Short History of the Author.”

We believe she was born circa 1812 and raised in Greene County, Tennessee. That her family was one of the first set free by a Virginian she identifies only as Mr. Noddie. And that young Malinda was well educated for her time.

To Liberia and Utopia

Greene County was a beehive of abolitionist activity. A Manumission Society had been active since 1815, and the first abolitionist newspaper, The Emancipator, was published in 1820 — about the same time Tennessee passed laws restricting free blacks. Colonization organizations whose mission was to send free blacks to Liberia sprang up, the Tennessee Colonization Society among them. From about 1830 to 1860, it’s believed some 700 African Americans left Tennessee for Africa thanks to their efforts.

At 19, Russell gathered what money she had and left home, headed to Liberia. Applicants for passage had to prove they were of good moral character. In her case, she traveled with a written endorsement from a Dr. More attesting to her worthiness. But something happened on the way to Utopia. Russell’s journey was cut short when she was robbed. Suddenly penniless, she was forced to stop at Lynchburg, Virginia.

Finding a Husband and a Mentor

It was there she met Anderson Vaughan, the man who became her husband. Just four years into their marriage, he died. But brief as it was, their union left Russell (who kept her maiden name) with an invalid son she described as “crippled.”

She found employment with a local family as a cook, traveling companion and nurse, supplementing her income as a laundress to help support herself and her son. And it was in Lynchburg that a free woman named Fanny Steward taught Russell how to cook with recipes from The Virginia Housewife, written by Mary Randolph in 1824. Russell had no trouble mastering Mary Randolph’s recipes; but it was with pastry and desserts that she excelled.

She eventually saved enough money to move back to Tennessee, where she may have had family and a support network to help with her son.

Guerrilla Attack

Russell ran a boarding house near Cold Spring for three years before opening and operating a successful pastry shop for six years. With hard work and frugal living, she was able to earn enough to support herself and her son.

Then, once again, everything was taken from her. On January 16, 1864, she was attacked and robbed by what she called a “guerrilla party.” She had caught the attention of a group of white men who believed blacks — especially black women — had no business owning property or earning good money. And, adding insult to injury, the mob threatened her life and that of her son if she revealed their identities, suggesting she knew them.

It was the straw that broke the camel’s back. Malinda Russell left the South, “at least for the present, until peace is restored,” for the small village of Paw Paw, in southwest Michigan, having read its description as the “Garden of the West.”

Writing her book in Paw Paw

Again, not much is known about this part of her life. But it’s thought she may have been working again as a cook and/or pastry chef while writing her book. Her goal was to earn enough from book sales to fund her return to Tennessee and reclaim her property.

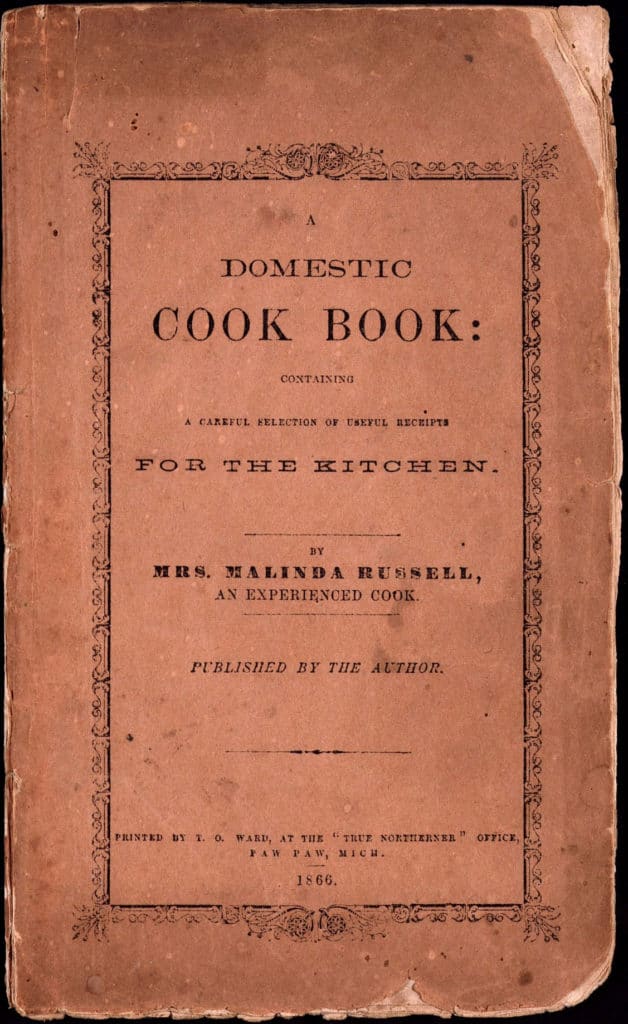

In May of 1866, the first known cookbook by an African American woman was published. Today, the best-known, if not the only, copy is held in the Janice Bluestein Longone Culinary Archive at the University of Michigan Special Collections. Age-tanned and foxed, it is a fragile, 39-page collection of 265 recipes that includes household hints and medicinal remedies.

Up in Smoke

“I publish my Cook Book, hoping to receive enough from the sale of it to enable me to return home.” But it’s unlikely Malinda Russell’s dream of returning to Tennessee came true. Shortly after her book was published, Paw Paw’s business center was devastated by a series of fires. In 1866, both sides of Main Street were partially destroyed; then, in the spring of 1868, a fire that burned for two days took what was left of the north side of Main Street and its businesses.

Sadly, the fires also seem to have taken any trace of whatever happened to Malinda Russell and her son with them, much to the dismay of historians and culinary researchers.

A Legacy in 39 Pages

Malinda Russell was a free woman of color, a hard-working single mother, and a business owner esteemed by the women in her community. Their endorsements in the book’s preface didn’t just make business sense — they reflected her integrity in acknowledging everyone she believed responsible for her talent and her book’s publication.

Award-winning food and nutrition journalist, educator and activist Toni Tipton-Martin calls Russell’s slim volume “a culinary Emancipation Proclamation for black cooks” and every African American chef laboring under the stereotype that while they could master “soul food,” they didn’t have the chops to master the fancy-schmancy European dishes thought of as traditionally “white” food.

In 39 pages, Russell shattered that stereotype. Far from relying on rustic recipes, she offered sophisticated food, drawing from European cuisine with recipes for elegant desserts like floating island, along with items like catfish fricassee, Irish potatoes with cod, and a sweet onion custard. But if you’re hoping to replicate Russell’s recipes, you better know your way around a kitchen. Take, for example, her recipe for “Cream Cake,” consisting of one sentence: “One and a half cup sugar, two cups sour cream, two cups flour, one or two eggs, one teaspoon soda; flavor with lemon.” That’s it.

In today’s parlance, Russell also managed to throw a little shade in the introduction to her book, acknowledging she learned to cook “after the plan of the Virginia Housewife” from “Fanny Steward, a colored cook of Virginia.” At a time when white Southern women often claimed dishes as their own without crediting, or even mentioning, the enslaved or underpaid cooks who invented or prepared them, Malinda Russell’s introduction set that to rights with her credit to Mary Randolph alongside a full-on shout out to Fanny Steward.

A Domestic Cook Book Containing a Careful Selection of Useful Receipts for the Kitchen may have been just 39 pages. But with those 39 pages, Malinda Russell earned her place in history by paving the way for every African-American cookbook author to follow.

SOOO GOOD I LOVED IT AND IT HELPED ME ALOT TY