Long before Steppenwolf told us we were “Born to be Wild” and “choppers” and “ape hangers” became part of cycling lexicon — a handful of gutsy female riders slid onto the seats of Wagners, Indians and Harleys, and grabbed the handlebars to become pioneers in the world of motorcycling. They are this Wednesday’s Women.

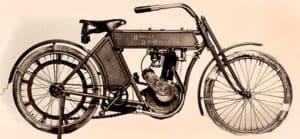

Motorcycle historians can’t agree on who built the first motorcycle, or even on the true definition of a motorcycle. But they do agree that America’s first self-propelled two-wheeled vehicle was built around 1869 by New Hampshire native Sylvester Roper.

It was a steam-powered bicycle he called the “Roper Steam Velocipede.” Sixteen years later, Germany’s Daimler attached an internal combustion engine to his wooden frame with iron-banded wooden wheels in what some believe was the first real motorcycle. But whether powered by steam or internal combustion, every motorcycle on the road today got its start as your basic bicycle with an attached engine.

Prices for these earliest versions are lost to history. But by 1909, the price of a Harley-Davidson (founded in 1903) motorcycle was $325, while a Ford Model T automobile would set you back $850. By 1915, Ford’s assembly-line system brought that price down to $440, making cars far more accessible. Motorcycle sales tumbled along with car prices, until most bikes were being sold as recreational vehicles to a mostly male audience.

But, much less remembered are the handful of women who were gender pioneers in this world of motorcycling. These are their stories.

CLARA WAGNER

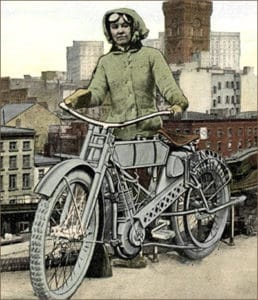

Fifty-nine years before Peter Fonda flashed those pearly whites behind the handlebars of his custom Captain American chopper in “Easy Rider,” 18-year-old Clara Marian Wagner was taking top honors in a 365-mile motorcycle endurance race.

Her father owned the Wagner Motorcycle Company. And when Clara joined the Federation of American Motorcyclists (FAM) in 1907 at just 15, she became its first female member. Two years later, when Wagner rolled out a woman’s “drop-frame” bike, Clara slid onto the seat and put the company on the map as the world’s first documented female motorcyclist.

Denied her trophy

In 1910, riding a 4-horsepower motorcycle, Wagner achieved a perfect score of 1000 in a 365-mile endurance race from Chicago to Indianapolis in bad weather, on mud-covered, pothole-pitted roads. She was all of 18. But the judges disqualified her as an “unofficial registrant” on the grounds that motorcycling was too dangerous for women, and denied Wagner the winning trophy.

Though Clara Wagner didn’t come home with the top prize, she became famous when her image appeared on a series of postcards hailing her as “the most successful and experienced lady motorcyclist” who rode the first bike designed especially for women.

DELLA CREWE

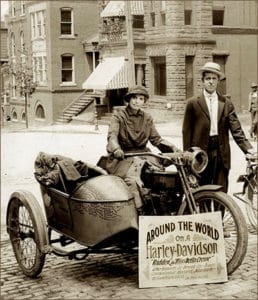

Thirty-year-old manicurist and seasoned traveler Della Crewe was planning her next adventure in the spring of 1914. Having traveled alone throughout North America, Alaska and Panama, she was bored with the same old same old of trains and steamships. So when a nephew suggested a motorcycle, Crewe jumped at the chance, eager for the freedom and mobility to see the world in a different way.

Ten days after purchasing a two-speed Harley-Davidson, which she christened the “Silent Grey Fellow,” Crewe stowed 125 pounds of luggage in an attached sidecar and hit the road from Waco, Texas, to New York City. Her traveling companion would be a Boston bull pup she named Trouble.

Gauntlet of obstacles

Starting in June of 1914, with sightseeing tours along the way, she didn’t reach New York until December. She slid along muddy roads and over the occasional stump that knocked her sidecar out of alignment. Stopped and quarantined in Indiana due to an outbreak of hoof and mouth disease there, only her promise that Trouble would stay in the sidecar let her continue. Sub-freezing temperatures and heavy, drifting snow in the Midwest slowed her down. And at the Pennsylvania-New York border she had to hire a farmer and his horse to pull her, Trouble, and the Harley out of heavy, wet clay that stuck to everything and gummed up her wheels.

Arriving in New York City in December of 1914, she was described as wearing four coats, four pairs of stockings and heavy sheepskin shoes. As for Trouble, he braved the cold sporting a special, made-to-order sweater.

5,378 miles

All told, Della Crewe covered 5,378 miles and 10 states over six months, declaring, “I had a glorious trip. I am in perfect health, and my desire is stronger than ever to keep going.” And keep going she did — just not the way she expected.

Crewe had planned to sail from New York to Europe. But as World War I raged overseas, Plan A had was shelved. Not to be deterred, Della Crewe loaded her Harley onto a southbound ship to Florida, from where she would explore the American South, Cuba and South America from behind the handlebars, with Trouble by her side.

EFFIE & AVIS HOTCHKISS

It was 1915 when Brooklyn mother-daughter duo Effie and Avis Hotchkiss took to the open road on a three-speed Harley-Davidson, earning a place in history as the first women to have made a cross-country, round-trip motorcycle journey.

Bored bank clerk

Effie Hotchkiss, at 26, was bored with her job as a bank clerk. A single professional, she was described as a bit of a tomboy with a need for speed and a yen for adventure. Using money left to her by her late father, she bought a Harley-Davidson and began planning a trip West to see the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco.

Naturally, her 56-year-old mother, Avis, did what all mothers do — she worried about her daughter heading into unknown territory alone. So the pair struck a deal. Effie would add a sidecar to her Harley and Avis would tag along. And so it was that, with Effie behind the handlebars and Avis and their luggage stowed in the sidecar, the pair rolled out of Brooklyn, headed for the open road.

Gauntlet of obstacles

The 1915 issue of Harley-Davidson Dealer magazine described them as meeting “bad roads, heat, cold, rain, floods and all such things with a shrug of their shoulders” on a route through upstate New York; across Chicago to St. Louis; through Kansas and Colorado; and on to Santa Fe into Arizona before reaching California. They rode in 120˚ temperatures; encountered rattlesnakes which Effie dispatched with her handgun; and got up close and personal with a coyote, who joined the rattlesnakes in the great hereafter. And when, in New Mexico, they ran out of spare inner tubes, the resourceful Hotchkiss women fished a blanket out of their luggage, cut it to the length of an inner tube, rolled it as tightly as possible and packed it into their tire.

Finally reaching the Pacific coast, they rode down to the water’s edge where, in a symbolic coast-to-coast gesture, Effie poured a jar of Atlantic Ocean seawater, stowed in the sidecar along with Avis, into the Pacific.

A ride into history

After exploring the World’s Fair in San Francisco, Effie climbed back behind the handlebars, Avis slid into her sidecar, and they headed home. Effie and Avis Hotchkiss left Brooklyn in May and returned in October, putting 9,000 miles on their odometer and cementing their place in motorcycling — and women’s — history.

AUGUSTA & ADELINE VAN BUREN

When New York socialite sisters and descendants of President Martin Van Buren Augusta (“Gussie”) and Adeline (“Addie”) Van Buren plunked down $275 each for a pair of Indian Power-Plus motorcycles in 1916, they aimed to kill two birds with one stone.

With America on the brink of entering World War I and Congress locked in a debate over expanding the military, the sisters sensed which way the wind was about to blow. So they togged themselves out in sturdy men’s riding leathers and took the handlebars of their Indian bikes, determined to prove women were as capable of serving as military dispatch riders as men. In the process, they would knock down one of the main arguments used to deny women the vote — they were not participants in the national defense.

Pike’s Peak

They left New York on July 4, 1916, on a trip that took just over two months and covered 5,500 miles of unpaved roads before they reached the US-Mexico border at Tijuana. They overcame physical barriers like the Rocky Mountains and rode to the top of Pike’s Peak, completing the 14,114-foot climb on their bikes and becoming the first women to summit the peak by motorcycle.

They faced miles of muddy roads, at one point becoming so mired they abandoned their bikes and walked to the nearest town in search of locals to dig them out so they could continue. Lost, and low on water west of Salt Lake City, a prospector eventually came to their rescue with water and directions to Reno.

Conquering physical obstacles on the road was one thing. But social barriers of the time were quite another. Remember the men’s riding leathers they chose for their journey? That did not sit well with some local police. This was, after all, still a time when many cities had laws on their books against people “appearing in dress not belonging to his or her sex.”

Arrested in their leathers

So Gussie and Addie Van Buren, in their practical leather pants, jackets, helmets and boots, were arrested more than once before arriving in California on September 8, 1916.

When they returned home, Adeline Van Buren applied to join the military as a dispatch rider, but was rejected. Articles in contemporaneous cycling magazines heaped praise on the bikes, but not the sisters — their history-making achievement was described as a “vacation.” But the Van Buren sisters’ rebel spirits were undaunted — Adeline earned a law degree from New York University, while Augusta became a pilot in the “99s,” a group of women flyers founded by Amelia Earhart.

Their accomplishments failed to achieve their primary goal of opening the military to women. But Augusta and Adeline Van Buren at least proved the old saw that sometimes the best men for a job could be women. The Van Buren sisters were inducted into the American Motorcycle Association’s Hall of Fame in 2002.

BESSIE STRINGFIELD

If I told you Bessie Stringfield began riding at age 16; completed eight solo cross-country tours; rode alone through 48 states, including the Deep South, and toured parts of Europe by motorcycle, you might think she was no different than Clara Wagner, the Van Burens or Avis and Effie Hotchkiss. But you’d be wrong.

Gender and racial barriers

Bessie Stringfield was an African-American woman born in Jamaica and raised in a devout Irish Catholic Boston household who, in a double-whammy, smashed both gender and racial barriers from behind the handlebars of her Harley-Davidson motorcycles (she owned 27 over the course of her lifetime).

Stringfield started riding at 16 on a 1928 Indian Scout — a present for her 16th birthday — but soon switched to Harley-Davidsons. As soon as she graduated high school, she biked throughout all of New England. At age 19, she took off on a series of what she called her “penny tours” — pennies tossed onto a map of the United States determined her destinations. Apparently one of those pennies landed in California, since, in 1930, Stringfield became the first African American women to make a solo cross-country motorcycle journey.

Sleeping at gas stations

Her travels took her through the Deep South at a time when racism was a palpable threat. She later recalled, “people were overwhelmed to see a Negro woman riding a motorcycle.” Not welcome in many hotels and restaurants in the Jim Crow era, Stringfield used The Negro Motorist Green Book to find safe places; she stayed with black families along her route or, when all else failed, slept on her bike in filling station parking lots. Held up as a champion of civil rights for women and African Americans, Stringfield pooh-poohed that notion, insisting she was just doing her own thing: “What I did was fun, and I loved it.”

Riding solo, she supported herself along the way by picking up jobs as a stunt rider in local fairs and carnivals. She also competed for prize money in races, which she often won disguised as a man. But when judges discovered that a woman of color had bested the male riders, Stringfield was denied the prize money.

Military dispatch rider

It was during World War II that Bessie Stringfield accomplished what the Van Buren sisters set out to do in 1916. She served as a civilian military dispatch rider for the U.S. Army. The only woman in her unit, she carried documents to and from home- front bases with a military crest affixed to the front of her Harley.

When the American Motorcycle Association opened its Motorcycle Heritage Museum in 1990, Bessie Stringfield was part of its “Women in Motorcycling” exhibit.

She was inducted into the AMA Hall of fame in 2002. Fourteen years later, 200 female riders traveled to Bessie Stringfield’s South Florida home to honor this pioneer in motorcycle history.

Thank you for the awesome history knowledge of women and motorcycles.