“And though she be but little, she is fierce.” Shakespeare’s line from A Midsummer Night’s Dream was written a full three centuries before our Wednesday’s Woman was born. But “fierce” doesn’t begin to do justice to Marjory Stoneman Douglas.

Today, most of us only know her as the namesake of the high school where 17 lives were taken on Valentine’s Day 2018. But, like the students from that school now rising up to demand change, Douglas was an outspoken, intelligent, fearless activist for what mattered most.

Born in 1890, Marjory Stoneman was determined to go to college — Wellesley College, to be exact, where she joined the first suffrage club with six classmates, earned straight A’s, and was named Class Orator when she graduated as an English major in 1912.

Newspaper family

Two years later she met Kenneth Douglas; he was well-mannered, 30 years her senior, and claimed to be a newspaper editor. Surprised and delighted by his attentions, Marjory married him within three months. But Douglas proved to be a con artist (and possible bigamist) who tried to scam his new father-in-law and was eventually jailed for writing bad checks. Marjory ended the marriage and joined her father and his wife in Miami, where he owned the local newspaper that became the Miami Herald.

She arrived in Miami in 1915 as a temporary hire, filling in for the Herald’s society reporter. Two years later, with America poised on the brink of World War I, she was assigned to a story about the first Miami woman to enlist in the US Naval Reserve. The interview subject never showed up. But rather than give up on a good story, Douglas became the story — she enlisted as a yeoman (F) first class in April 1917, stationed in Miami.

Miami Herald Assistant Editor

Following her discharge a year later, she joined the American Red Cross as a volunteer in Paris, helping to care for displaced war refugees. It was there, as the Red Cross was winding down its war efforts, that her father cabled her with a job offer as assistant editor of the Herald.

Douglas returned to Miami in 1920 and, for the next three years, worked on the Herald’s editorial page while churning out a daily column called “The Galley.” Its original purpose was to cover society doings — weddings, teas and “women’s issues.” But Douglas, who would become known for her gumption, floppy hats and dark round glasses, soon proved to be a feisty, outspoken voice for issues that mattered to her — civil rights, urban planning and sanitation, women’s rights and racial injustice.

By late 1923, Douglas, feeling the pressure of constant deadlines, the demands of a daily column, growing friction between her and the paper’s publisher, and disagreements with her father, left the Herald to pursue a freelance career. Left to her own devices, she published more than 100 short stories and nonfiction pieces for the Saturday Evening Post. The change suited Douglas to a T — she admitted she was never a very good employee, didn’t like taking orders, and valued her independence and solitude.

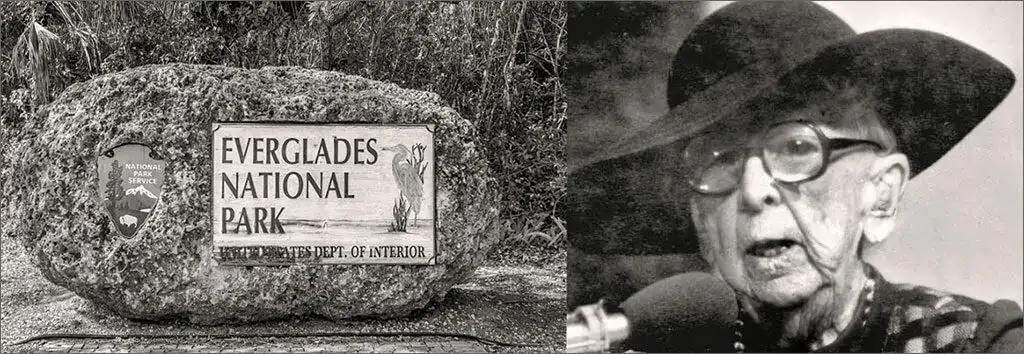

But her quiet life took a change when fellow environmentalist and landscape architect Ernest Coe asked for her help in saving the Everglades from the governor’s plan to drain what was seen as no more than a swamp for urban development. Coe conceived the concept of an Everglades National Park in 1928. Officially designated by Congress in 1934, it would not open to the public until 1947.

Douglas was skeptical at first. Having visited the Everglades numerous times, she found them “too buggy, too wet, too generally inhospitable” for her taste. But as she began to dig into the Florida landscape, with its unique geography, she came to understand how the ‘Glades functioned, and how vital they were to Florida’s entire ecosystem. So when she was visited by a friend who pitched the idea for a book on the Miami River as part of his company’s series on Rivers of America, Douglas countered with the idea of a book on the Everglades.

Landmark book

The resulting book was called The Everglades: River of Grass. It had taken Douglas five years to research and write, and was published to coincide with the dedication of Everglades National Park in 1947. Considered a classic, it shaped America’s perception of our wetlands and serves to this day as the defining work on the Florida Everglades. It also marked the beginning of the fight of Marjory Stoneman Douglas’ life.

When the US Army Corps of Engineers wanted to straighten the Kissimmee River with dams, pumping stations, canals and levees, Douglas fought them with detailed scientific explanations of how the Kissimmee’s long, winding path from Central Florida to the Everglades served a vital role as a filtering mechanism. When the sugar industry near Lake Okeechobee proposed dumping toxic waste into the Everglades, Douglas rose up and fought. At age 79, she founded Friends of the Everglades to bolster support in her fight against construction of a jetport in the ‘Glades — a project that was halted when President Nixon vetoed its funding thanks to the work of Douglas and her group of environmentalists. And when South Florida’s Water District allowed waters of the Everglades to rise to levels that wound up killing Florida’s native deer population, Marjory Stoneman Douglas didn’t hesitate to take them on, too.

High School Named

Douglas was 100 years old when Broward County named its new high school for their renowned centenarian in 1990. Three years later, she received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Bill Clinton. Ironically, she was invited to stay and watch as Clinton signed the Brady Bill into law, establishing a federal background check for those seeking to purchase firearms.

Marjory Stoneman Douglas died in 1998 at the ripe old age of 108. She asked that her ashes be scattered over her beloved Everglades National Park.

Over the course of her 108 years, words like fierce, feisty, fearless, outspoken, articulate, intelligent, passionate and cantankerous were used to describe Marjory Stoneman Douglas. Chances are, she would be proud of the students from the high school that bears her name as they stand up, speak out, and fight for the cause of their lives, channeling their anguish into a fierce activism.

Peg, while she never had children to carry her DNA, those MSD students are certainly doing their namesake proud. Somewhere out there, a feisty little angel with a floppy halo and big round glasses must surely be smiling!

One can’t help but believe her fighting spirit lives in the halls of the school that bears her name and inspires those students to use their words to effect change.