Life for a woman born in the 1800s was full of gender-based taboos and restrictions. She couldn’t vote, run for or hold office. Couldn’t own property or, with few exceptions, get an elite education. Couldn’t serve in the military or on a jury. And she couldn’t easily escape a distasteful or abusive marriage. For a woman to enjoy all the freedoms denied her simply by being born female, there was only one option: live as a man.

Charlotte Darkey Parkhurst, born in Sharon, New Hampshire, in 1812, did just that.

Remaking herself as a boy

Details are scarce about her early life, and reports differ — did her mother die in childbirth or shortly thereafter? was her father unable or unwilling to care for her? was she placed under the care of Boston Children’s Services, well known as the oldest child welfare agency in the nation? The only thing researchers and authors agree on is that when she was 12 years old, she ran away, dressed in boys’ clothing, leaving Charlotte behind to live as a male named Charley Parkhurst.

She met livery stable owner Ebenezer Balch in Worcester, Massachusetts. He took the child he thought was an orphan boy under his wing, providing bed and board in exchange for mucking out stalls, washing carriages and scrubbing floors. But when Balch saw Charley’s easy rapport with horses, he took her on as his protégé, training her to drive carriages pulled by two-, four- and six-horse teams. Thanks to Balch, Charley Parkhurst became one of the best coachmen on the eastern seaboard.

Gold rush

But as news spread in 1848 that “there’s gold in them thar hills,” people from across America begged, borrowed and stole to get to California in hopes of striking it rich. Mining towns sprang up to meet their needs with saloons, brothels, hotels and businesses whose owners hoped to make their own fortunes. Dirty, dusty and chaotic, they were home to bandits, gamblers, prostitutes and violence. In short, Gold Rush California was no place for a lady. Then again, nobody ever mistook Charley Parkhurst for a member of the fairer sex.

Taking Horace Greeley’s advice to “go West, young man,” she arrived in San Francisco in 1851, just shy of 40 years old, with the goal of becoming the best stagecoach driver in California. It was a job requiring good judgment, dexterity and considerable strength. A good “whip,” as drivers were called, earned $125 a month plus room and board, a princely salary for the time. And Charley Parkhurst was good — by all accounts, she was considered “the best damn driver in California.”

Rattlesnakes, grizzlies, highwaymen

Parkhurst pulled coaches laden with heavy boxes of gold and up to 20 passengers, driven by six-horse teams over jolting terrain and makeshift trails. She worked double shifts and drove through the night, in all kinds of weather, for double pay, always at risk from rattlesnakes, grizzlies, Indians and highwaymen. Her routes ran between gold-mining outposts and major towns like San Francisco and Sacramento, including the “great stage route” from San Jose to Oakland, and from San Juan to Santa Cruz. In 1854, a trip from San Francisco to Santa Cruz took two days; today it’s just under an hour and a half down California Route 17 and I-280 South.

Employment records for Wells Fargo, the most important combination mail-delivery service, bank, express agency and stagecoach company in the West, describe Parkhurst as standing 5’6″, with alert grey eyes — one of which was covered by a black eye covering a facial defect from a horse kick to the face. While Charley, by some accounts, cussed, drank in moderation, smoked cigars, chewed tobacco and rolled dice with miners and other whips, she was also described as shy, speaking little, and never one to engage in brawls.

Sweets for the children

Throughout her career, she wore blousy pleated shirts cinched at the waist with a wide leather belt. Durable blue denim jeans sold by Levi Strauss, with either a buffalo-hide cap or wide-brimmed hat shielding her face, completed her dress. And she was never without long-fingered, embroidered buckskin gloves that served to hide small, smooth hands. The only feminine trait one person ever recalled was Parkhurst’s fondness for children. It’s said Charley Parkurst always kept candy in her pockets for the mining towns’ children drawn by the excitement of an arriving stagecoach.

She was also handy with a .44 pistol, which she kept tucked in her belt. After all, those were the days when gangs of desperadoes staked out stagecoach routes, leveling their guns at drivers and terrifying passengers to shouts of, “Throw down the gold box!” One particular bandit nicknamed Sugarfoot (who put cloth sugar bags over his shoes to hide his tracks) hit Parkhurst’s stage twice. The first time, he got away with the gold.

Shot a robber dead

But the second time proved his undoing. This time, when he and his gang accosted the stage, Charley didn’t stop. She cracked her whip and the team of horses bolted, surprising the highwaymen and giving Parkhurst time to spin around, aim and and fire her pistol. Sugarfoot was later found dead, gut-shot, with a bullet to the belly. In appreciation, Wells Fargo rewarded Charley Parkhurst with the traditional solid gold watch and chain.

After the Civil War, the Pacific Railway Acts paved the way for westward rail expansion. As James P. Ronda, co-author of The West the Railroads Made wrote, it brought “the West into the world and the world into the West.” Trains soon began to replace the stagecoach, bringing news, mail, food and trade goods to California.

With the rails gaining popularity, and complaining of “sciatic rheumatism” from decades of being pounded and bounced around in the box of countless stages, Charley Parkhurst retired in the late 1860s. She tried her hand at running a saloon and operated a stagecoach station where drivers exchanged teams and gave passengers a few minutes to stretch their legs before going on their way. Worked as a lumberjack in Northern California, earning top dollar, raised cattle and chickens — and even joined the local Odd Fellows lodge.

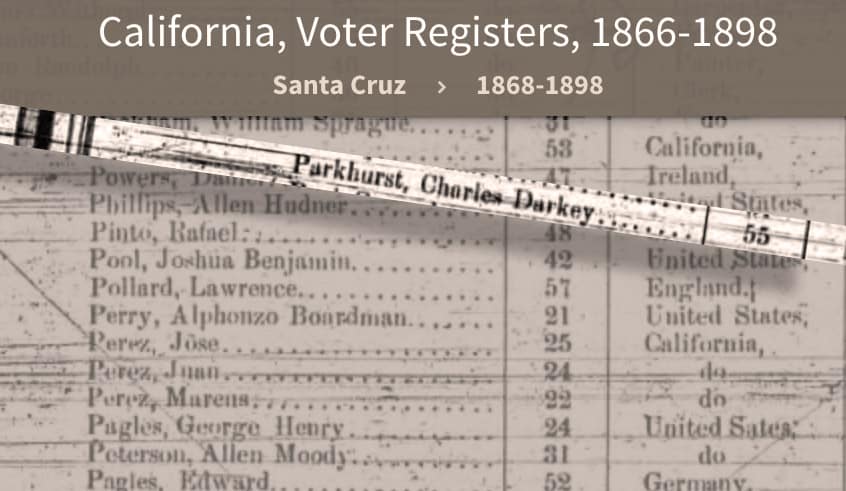

Registered to vote

At the same time, Charley Parkhurst took advantage of an important right denied to women of her time. On April 25, 1867, one Charles Darkey Parkhurst, age 55 and a resident of Soquel, registered to vote in the 1868 presidential election pitting former New York Governor Horatio Seymour against Civil War General Ulysses S. Grant. Her name appears as registrant #1039 in Santa Cruz County’s Great Register in the Hall of Records. While California women got the vote 44 years later, in 1911, it wouldn’t be until 1920 that the 19th Amendment gave America’s women the franchise to vote in national elections.

Early in 1879, Charley Parkhurst started complaining of a sore throat and a swelling on one side of her tongue, found to be cancer of the mouth and throat from a lifetime of smoking and chewing tobacco. She died in December, at age 67, in a small cabin near Watsonille, “her accumulations regular and her wealth considerable,” according to the Santa Cruz Sentinel. The San Francisco Call remembered Parkhurst as “one of the most dexterous and famous of the California drivers … and it was an honor to be striven for to occupy the spare end of the driver’s seat when the fearless Charley Parkhurst held the reins of a four or six in hand.”

Her true sex discovered

Parkhurst left instructions to be buried in her everyday clothes. As was the custom, close friends came to wash and prepare the body for burial. Only then was the secret Charley took to her grave discovered. Refusing to believe their eyes, they summoned a doctor who confirmed that the tough-talking, tobacco chewing master whip they had all known as Charley Parkurst was, in fact, a “well-developed woman.”

Charlotte “Charley” Parkhurst, a.k.a. “One-Eyed Charley,” was buried in Watsonville, California’s, Pioneer-Odd Fellows Cemetery. When it fell on hard times in 1955, a local historical association had her remains exhumed and reburied with a historical marker reading:

“Charley Darkey Parkhurst (1812-1879) Noted whip of the gold rush days. Drove stage over Mt. Madonna in early days of Valley. Last run San Juan to Santa Cruz. Death in cabin near the 7 mile house. Revealed ‘one-eyed Charley’ a woman. First woman to vote in the US November 3, 1868.”*

A California legend

Drive California’s fabled stagecoach trails today, and you’ll find plaques honoring Charley Parkhurst. There’s a section devoted to her at the Wells Fargo Museum on the corner of Montgomery and Post Streets in San Francisco. And scholars writing on the transgendered community have included Charley Parkhurst. But who is to say whether she identified as a man or simply chose to experience all the freedoms life had to offer by living her life as one?

* The question as to whether Parkhurst ever actually cast her ballot remains unsettled. While many historians have their doubts, one Santa Cruz County historian and author (the late Phil Reader) has cited a notation in the county's Great Register indicating she did.

One of the more accurate accounts of Charley’s (Charlotte’s) life and story. Thank you for your interest in Charley’s Story…well done!

My brother Charles L. Parkhurst and I are currently working on our version. As you know, there are some unanswered questions early in Charlotte’s life. We hope to get some answers…what was a project, has become a quest.

If you can provide any additional sources not already known, please do so, it would be very much appreciated. Thanks again.

Respectfully,

Tom R. Parkhurst

charley Darkey parkurst was a very brave woman