Madeleine Albright, America’s first Secretary of State, famously said “there is a special place in hell for women who don’t help each other.” If that’s true, writer and adventurer Grace Gallatin Seton certainly isn’t there.

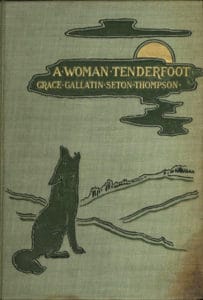

Grace Gallatin was writing for San Francisco newspapers at 16 under the pen name Dorothy Dodge. But her first book, titled “A Woman Tenderfoot,” was published in 1900. It chronicled her trip through the Rockies on horseback with then-husband, British-born Ernest Thompson Seton, a nature writer from the movement that gave us Jack London.

In it, she connected the dots between literature and women’s rights, encouraging female readers to expand their physical and social horizons with travel to the remote reaches of America traditionally seen as places to be conquered only by men. Providing the fine points of how to dress in the field, what to pack for hunting camp and how to shoot, she even designed a riding costume that allowed women to ride astride (as opposed to the more ladylike side saddle) with the same freedom as a man.

World War I and the French Front

Seton was in France in 1916 as two of World War One’s most decisive battles were fought — one at Verdun, the other at the Somme. She organized and directed a woman’s motor unit called the Welfare of the Injured Women’s Unit to work with the Red Cross, bringing food to medical tents set up behind the French front lines.

She described her work in a 1920 issue of the Journal of National Institute of Social Science: “The little fleet of eight Ford Camionettes…organized and operated entirely by women, traveled thousands of miles; carried tons of food and comforts to the wounded during the first months to the Emergency and Field and, later, to the Base Hospitals; and kept open the doors of several hospitals by its service, when the breakdown of the French Transport System was at its worst.”

Grace Gallatin Seton was awarded medals from France and England for her service. But more importantly, it was partly through her efforts in World War I that Woodrow Wilson was persuaded to accept women’s suffrage after the war.

Speaking of Suffrage …

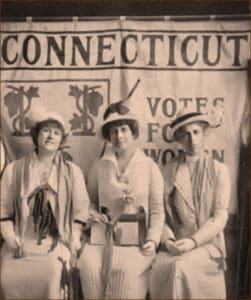

Despite being a patriot, adventurous explorer, artist and writer, Seton was, above all, a feminist who, in her own words, was “one of those people born believing in suffrage.” Active in the women’s movement since age 17, she led the Connecticut Women’s Suffrage Association for a decade (1910-1920). So it’s more than a little ironic that she herself was denied the franchise because she was the wife of a British citizen.

In 1907 Congress passed the Expatriation Act stating U.S. women married to non-citizens were no longer considered Americans. Only if their husbands completed the naturalization process could they regain their own citizenship. It was only after women gained the franchise in 1920 that they began lobbying lawmakers to recognize their citizenship should no longer be harnessed to that of a man.

Explorer and Geographer

After the war, Seton set out on a series of trips without her husband to Egypt, China, Africa, India, Japan, South America and Southeast Asia — places very few western women had seen. And everywhere she went, often the only woman on the expedition, she talked with women about politics, social structure, customs and their dreams for the future.

Not the typical American tourist, she rode a donkey through the Libyan desert and sat atop an elephant on safari through the jungles of Vietnam; organized a tiger hunt in India and witnessed a military uprising in China. The result was four travel books, the last titled “Poison Arrows,” about the matriarchal Moi tribes of Southeast Asia. In 1931 she wrote a long article for the New York Times about her time with the Moi, whose men ranked second in importance to their women, that ran with a photo captioned “Warriors of a Matriarchy,” showing a group of female Moi hunters with cross bows and arrows.

Around the same time, she became one of eight founders of the Society of Women Geographers. Founded in 1925, its purpose was to bring women together to share their interest in exploration and achievement, exchange knowledge derived from personal field work and encourage other women to pursue geographical exploration and serious research.

But her passion for adventure and the great outdoors outlasted her marriage to Ernest Thompson Seton. While she was traveling the world, her husband was traveling with his secretary. Accusations of infidelities on both sides flew and he divorced her in 1935. The day after the divorce, Ernest Thompson Seton married the secretary, who was 30 years his junior. Grace Gallatin Seton never remarried.

Supporting Women Writers

While she pursued her own writing career, Seton worked to promote and preserve the work of other women. But in the 1930s she turned her full focus to the cause. Eight years before women were granted the right to vote, Seton became president of Pen and Brush. Founded in 1898, the public nonprofit provided a platform to showcase the work of female artists and writers.

And during two terms as president of the National League of American Pen Women (1926-28 and 1930-32), she doubled the number of branches of that organization. NLAPW was founded in 1897, when female journalists were forbidden to join male-only professional organizations. A haven for women writers, artists and composers, prolific writer Eleanor Roosevelt was a Pen Woman both during her tenure as First Lady and after.

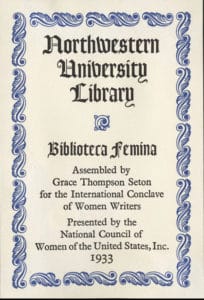

But it was as chair of letters of the National Council of Women (1933-1938) that Seton made what may be her most lasting contribution to feminism when she helped organize an international conference of women writers at Chicago’s Century of Progress International Exposition in 1933.

The Biblioteca Femina

While just about any major research library has collections of material on women’s issues, one devoted entirely to material written by women is hard to find. That is, unless you happen to be at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois. For it’s there you’ll find the 7,000-volume international collection of literature by women gathered for two Chicago World’s Fairs. Its pages offer a priceless window into the state of women, nationally and internationally, from 1833-1940.

From May to October 1893, Chicago hosted the World’s Columbian Exposition, attended by over 27 million people. One of its main attractions was the Woman’s Building, designed by 27-year-old architect Sophia Hayden. Inside was a collection of more than 7,000 volumes authored, illustrated, edited or translated by women from 40 states and 23 foreign countries, curated to highlight women’s contributions to print along with the literary and intellectual achievement of women. On display were manuscripts, rare books, popular fiction, scholarly works, self-published volumes, scrapbooks of journalistic writing, yearbooks, cookbooks, newspapers and musical scores.

Theodore W. Koch, Northwestern University’s library director, attended the Conclave and befriended Seton. By week’s end, the National Council of Women had donated 1,000 of these books to Northwestern. Named the Biblioteca Femina, after the first documented women’s library, founded in Italy in 1842, it serves as the core of the university library’s collection on feminism.

Legacy

Grace Gallatin Seton was 87 years old when she died of a heart attack at her home in Palm Beach, Florida, in 1959. She is buried in Putnam Cemetery in Greenwich, Connecticut.

Perhaps Carol Taylor, reviewing “A Woman Tenderfoot” for Mother Earth News in 1988, summed her life up best: “Grace Gallatin Seton is the grandmother every girl would like to have — independent, adventurous, faintly scandalous, impatient with timidity … an intelligent, gutsy, witty woman.”