At the heart of almost every important civil rights case for twenty years stood a tall, gracious woman whose goal was as simple as it would prove to be elusive: provide dignity for everyone. You may not know her name, but Constance Baker Motley has worked tirelessly behind the scenes to quietly change the course of American history.

Along the way, she racked up a list of “firsts.” Motley was the first black female admitted to Columbia University Law School. The first black woman to serve in the New York State Senate. She was the first black woman to argue before the United States Supreme Court; of her 10 Supreme Court cases, she won nine of them — the tenth was eventually overturned in her favor. Motley was also the first black female appointed to serve as a federal judge.

Constance Baker Motley was born in Connecticut in 1921. The ninth of 12 children, her parents came to the United States from the tiny West Indian island of Nevis. Her father was a chef at Yale University; her mother was a domestic worker. Going to school in largely white communities, her first experience with discrimination came at 15 when she was turned away from a public beach because she was black.

Always an ambitious student, she began studying black history and became the president of her local NAACP youth council. Though she aspired to become a lawyer, there was no money for college. After high school, Motley followed in her mother’s footsteps for a short time, struggling to earn a living as a domestic worker. She then found a job with the National Youth Administration — a New Deal program that provided work training and education for young Americans between the ages of 16 and 25. One of her roles at NYA was speaking on matters of public interest at community forums in the New Haven area.

Teenage activist

Motley was 19 when New Haven native Clarence Blakeslee, a wealthy white contractor and philanthropist, heard her speak at a local African-American social center about why the center wasn’t attracting the black community, as intended. Never shy, she raised eyebrows by pointing out the center’s board was 100% white and Yale-educated, which meant the black community had no opportunity for input and, therefore, no interest in the center. Motley so impressed Blakeslee that he reached out to the high school, researched her grades, then reached out to Motley with an offer to finance her college education.

She chose to attend Fisk University, a black college in Tennessee, partly because she had never been to the South — a rigidly-segregated society clearly defined by signs reading “Colored Only.” After her first year, she transferred to New York University, from which she graduated with a degree in economics in 1943. Columbia Law School followed, where she volunteered with the NAACP’s Legal Defense and Education Fund and clerked for Thurgood Marshall.

Civil Rights legal support

In 1946, armed with a newly-minted law degree, Motley began working full time for the civil rights group, earning $50 a week to prepare housing cases designed to overturn restrictions barring blacks from white neighborhoods. That same year, she married New York real estate and insurance broker Joel Motley, Jr.

As a young attorney, Motley’s strength was working behind the scenes, doing the painstakingly detailed preparation and presentation of lawsuits that would pave the way for blacks to become full participants in American society. Always elegantly dressed, with a classic string of pearls befitting a dignified, successful litigator, Motley spoke in a low, measured voice. But she soon found herself in the center of a firestorm in the South as blacks, along with their white allies, fought to bring an end to segregation that stretched back to post-Civil War Reconstruction.

Brown v. Board of Ed

As early as 1950, Motley was drafting complaints and preparing briefs for the landmark Supreme Court case of Brown v. Board of Education that, in 1954, declared state laws establishing separate public schools for black and white students unconstitutional. In 1957, she won the enrollment of nine black students to Little Rock’s Central High School in a case known as the “Little Rock Nine,” marked by President Eisenhower sending federal troops to escort the students into school.

The early 1960s, leading up to the passage of major civil rights legislation in 1964 and 1965, were marked by increasing national tension and major victories for the civil rights movement. And Motley was front and center. She represented black students seeking admission to universities throughout the South. In 1961 she won admission to the University of Georgia for Charlayne Hunter-Gault of PBS’s McNeil-Lehrer Report, NPR and the New York Times.

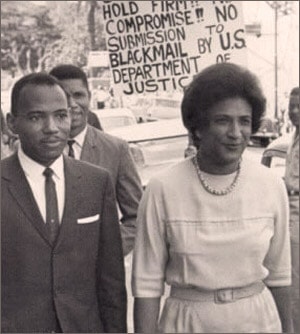

James Meredith’s attorney

That same year, Thurgood Marshall assigned Motley James Meredith’s case. She always said he gave her the case because she was a woman, his belief being that “the only people who were safe in the South were women — white and Negro.” While Meredith’s admission to the University of Mississippi in 1962 was a major victory for the civil rights movement, Motley — who had worked on the case for 18 months and made 22 trips to Mississippi — considered his 1963 graduation from Ole Miss one of the most thrilling days of her life.

Motley won cases that desegregated Memphis restaurants and Alabama’s whites-only lunch counters. She was a litigator and chief strategist for the Montgomery Bus Boycott. She fought for Martin Luther King, Jr’s. right to march in Georgia and, in 1963, visited him in his Birmingham, Alabama, jail cell. Motley sang freedom songs in bombed-out churches and spent a night with armed guards in the home of Medgar Evers, who was later murdered in his driveway by a white supremacist.

An adversary of George Wallace

She was also behind the scenes in 1963 when George Wallace, whose “Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever” speech will go down in history as one of the most strident racist rallying cries, yielded to hard-won court victories led by Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP’s Legal Defense and Education Fund. That victory led to Vivian Malone Jones’ admission to the University of Alabama.

By 1964, her high-level profile in the civil rights movement drew her into politics. She accepted the Democratic nomination to the New York State Senate on one condition — that it wouldn’t interfere with her NAACP work. She handily defeated her Republican rival to become the first black woman elected to that body, winning re-election in November.

But her career reached its apex in 1966, when President Johnson, acting on Senator Robert F. Kennedy’s recommendation, appointed Motley America’s first African-American federal judge. During her tenure, she ruled on behalf of welfare recipients, low-income Medicaid patients and a prisoner who had been unconstitutionally kept in solitary confinement for 372 days.

Women’s rights

And in 1978, her decision to allow female reporters into the New York Yankees’ locker room turned Major League Baseball on its head.

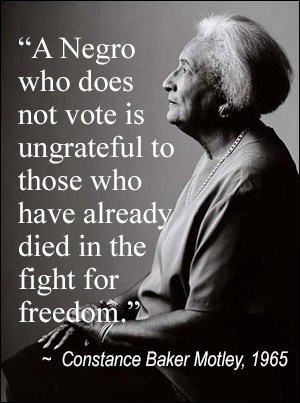

Judge Motley continued to serve as a federal judge until her death at age 84 in 2005 at New York University’s Downtown Hospital in Manhattan. Judge Kimba Wood of the Southern District of New York described her colleague as having the “strength of a self-made star” who, in her early days as a lawyer, faced constant condescension from the legal community simply “due to her being an African-American woman.” Nevertheless, she persisted. In her autobiography, “Equal Justice Under Law,” Motley wrote that defeat never entered her mind. “We all believed our time had come and that we had to go forward.”

During her lifetime, she was honored with the Candace Award for Distinguished Service by the National Coalition of 100 Black Women in 1984. Nine years later, she was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame. President Clinton awarded her the Presidential Citizens Medal, and the NAACP bestowed on Motley its highest honor, the Springarn Medal, two years before her death.

I salute her courage!!