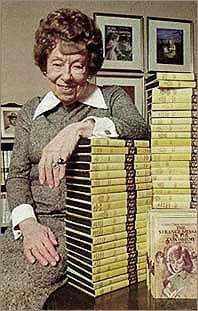

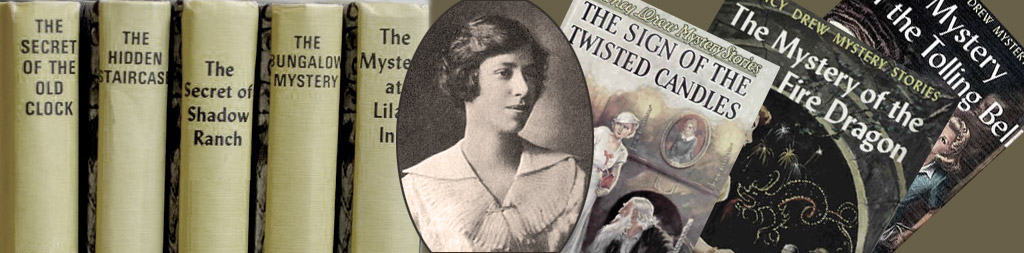

An avid reader for as long as I can remember, I grew up absolutely devouring the works of Harriet Stratemeyer Adams. But I never knew her by that name. To me, she was Carolyn Keene, author of all those wonderful Nancy Drew mysteries whose bright yellow spines lined my bedroom bookshelf. In a book publishing world long dominated by males, Adams became a stunning business success by offering young girls a strong, adventure-seeking literary heroine who controlled her own fate.

A Jersey Girl born in Newark in 1892, Adams graduated from Wellesley College in 1914, where she distinguished herself as an accomplished writer, pianist, and a journalist who worked as a college press correspondent and sold articles to large newspapers like the Boston Globe.

Fiction factory

She spent a year after graduation working as an apprentice to her father, Edward Stratemeyer, owner of the Stratemeyer Syndicate — a veritable fiction factory whose assembly-line system produced books specifically geared to young readers.

When her father succumbed to pneumonia in 1930, Adams became a senior partner in the company, overseeing all the behind-the-scenes people required to bring a book to market. A plot developer would be hired to outline the chapters of each book, after which a ghostwriter did the actual writing under a pen name, subject to final editing by yet another member of the syndicate.

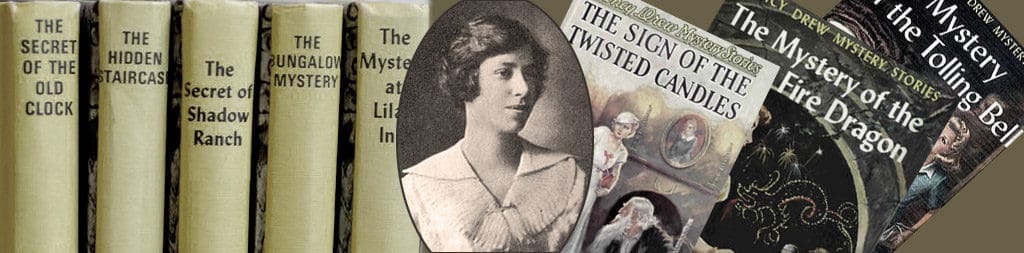

Harriet Adams wrote nearly 200 children’s books, including many of the Nancy Drew and Hardy Boys series. For more than 50 years, her books were read by generations of children. She wrote under the pseudonyms of Carolyn Keene for the Nancy Drew series; Franklin W. Dixon for the Hardy Boys; Victor W. Appleton II for Tom Swift, Jr.; and Laura Lee Hope for the Bobbsey Twins. Over the years, all four pen names would be shared by other authors.

Blue roadster convertible

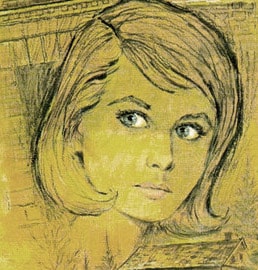

Adams’ Nancy Drew, girl detective, made her first appearance in 1930. No simpering maiden waiting to be rescued by a strong, handsome man, she got herself out of just about any dicey situation. Whether she was knocked unconscious, kidnapped or locked in a dark room somewhere, she always survived to chase the next villain in her snazzy blue roadster convertible, with true-blue boyfriend Ned Nickerson by her side.

Young readers found a new role model in Nancy Drew — plucky, confident, smart, athletic, and in charge of her own destiny. In the first book, The Secret of the Old Clock, we learned Nancy could drive a roadster and pilot a speedboat, repair motors, tend to a sprained ankle and, if that’s not enough, manage to find a long-lost will in an old clock! What young girl didn’t want to be just like her?

Over the years, Harriet Adams insisted Nancy Drew be held to high standards, personally approving cover art to ensure she was depicted “appropriately.” And while giving readers adventures with unfailingly happy endings, she always made sure each book contained some educational content. For example, in book 26, The Clue of the Leaning Chimney, readers learned a little about Chinese Ming pottery. And when Nancy went to Peru in book 44, The Clue in the Crossword Cipher, to unravel a clue leading to a fabulous treasure, readers got to explore Incan ruins and the Nazca Lines right along with her.

Forever unmarried

As times changed, the intrepid teenage sleuth ditched her sassy cloche hat and gloves, updated her hairstyle, and traded in her blue roadster more than once. But when the sexual revolution hit and Dr. Irene Kassorla (Hollywood psychotherapist and soap opera star) assured us “Nice Girls Do,” Nancy Drew didn’t. While she maintained her long — they first met in 1932 — relationship with steadfast Ned Nickerson, Adams always insisted their marriage would mark the end of the series.

In 1984, the Stratemeyer Syndicate was sold to Simon & Schuster, who have re-launched a new Nancy Drew series titled Nancy Drew Girl Detective. But Harriet Adams’ original classic series of Nancy Drew Mystery Stories that began in 1930 with The Secret of the Old Clock ended with book 175, Werewolf in a Winter Wonderland, in 2003.

Tie-in proucts

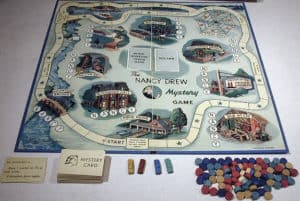

Since being introduced in 1930, Nancy Drew books have never been out of print. Their enduring popularity gave rise to an entire market of all things Nancy Drew. You can bring Nancy into your kitchen with the Nancy Drew Cookbook: Clues to Good Cooking. A short-lived TV series called the Hardy Boys/Nancy Drew Mysteries came into our living rooms in the late 1970s, but proved to be more about teenage heartthrobs Parker Stevenson and Shaun Cassidy than clever sleuthing and crime-solving. A label called Gumshoe Girls launched a line of Nancy Drew pajamas and accessories in 2003. And if you get tired of Scrabble and Monopoly, there’s even a classic Nancy Drew Mystery Game by Parker Brothers, dating to 1959.

Harriet Stratemeyer Adams died in 1982 at the age of 89 in Maplewood, NJ, after suffering a fatal heart attack. She was laid to rest in the city where she was born, in Newark’s Fairmount Cemetery.

But she leaves a remarkable legacy, having kept a thriving business afloat during the Great Depression and throughout World War II. Under her steady hand, series like Nancy Drew and The Hardy Boys have remained popular for generations, albeit updated to reflect changing stereotypes, ideas, politics and modern language of the 20th century.

Role models and reading skills

More importantly, Harriet Adams helped shape the imaginations of generations of children, provided them with a new role model, and may well be credited with getting more young people into the habit of reading than just about anyone else.

I read many Nancy Drew books in the last 60’s but also enjoyed Trixie Belden books written by Julie Tatham Campbell. Always an avid reader, I still spend many afternoons with a good book!

Nancy is my life! I own the whole book series and read them all over and over.

Never got into Nancy Drew but really appreciate reading about the lady who made her.