A practical and creative nineteenth-century boarding house owner, Mary Elizabeth Walton was used to solving mechanical problems. So it was only natural that, when the noise and smoke of the elevated railway next to her building became intolerable, she set out to reinvent the era’s train technology — and succeeded, even where Thomas Edison himself had failed.

After the Civil War, America’s Industrial Revolution lured middle-class workers from rural farms to factory jobs that were springing up at a dizzying pace in cities like New York, where they were soon joined by millions of European immigrants arriving in search of a new life. Songs and chants that had long marked the rhythm of manual labor were soon drowned out by the incessant clang, whir and throb of the new-fangled machinery powering urban factories.

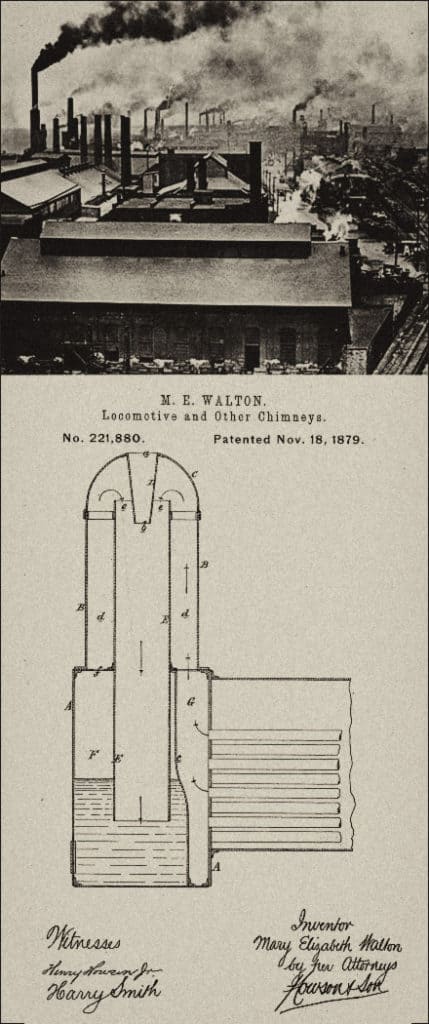

But factory jobs came with a noxious price. While they couldn’t know back then what was in the air they breathed, New Yorkers could literally see and smell it as oil and kerosene refineries, coal yards, varnish and fertilizer plants, ammonia works and factory smokestacks sent dense clouds of smoke billowing over Manhattan’s downtown.

Train pollution

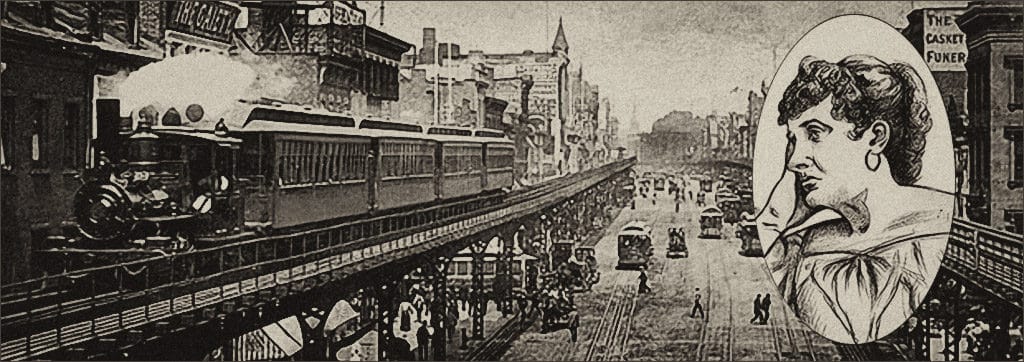

As if that wasn’t enough, contributing to the urban din and air pollution of 19th-century New York was the city’s solution to getting all those new workers to and from all those new jobs — a new system of elevated trains, or “els,” that clanged, puffed and belched smoke along nine miles of track that ran down most major thoroughfares of the city.

In 1879, Mary Elizabeth Walton owned a boarding house at 12th Street and 6th Avenue, smack up against the city’s new Gilbert Elevated Railway. She was an innovative, no-nonsense woman who saw a problem and set out to fix it. So when it came to the constant roar of the el’s steam engines, the smoke that belched from its stacks to leave a layer of soot on every surface, the sound of its screeching brakes and the vibrations that shook adjoining buildings, Mary Walton began to think seriously about ways to rid her neighborhood of its airborne and noise pollution.

Factory pollution control pioneer

The female inventor began by designing a device that forced smoke from locomotive, factory and residential chimneys through water tanks that dissolved and held the pollutants in suspension before discharging them into the city’s sewer system. In November of 1879, she was awarded U.S. Patent #221,880. Traveling to England to promote her invention, British officials hailed her device as “one of the greatest inventions of the age.” Perhaps not surprising, considering Charles Dickens’ 1852 description of the London fogs and “streets full of dense brown smoke.”

Unfortunately, trapping airborne pollutants did nothing for the elevated railways’ assault on city dwellers’ ears. In the words of one New York physician, “We see very little of the gentle decline of old age in New York City. The constant din of travel and traffic, borne for a time without evidence of injury, suddenly shows itself in a shattered nervous system and imminence of dissolution.”

Thomas Edison’s failure

The city called upon some of America’s finest machinists and inventors, including Thomas Edison, to find a solution. Edison spent six months looking for a way to deaden the noise of the elevated rails to no avail. It would take a woman who lived along the tracks to come up with a workable solution.

Mary Walton rode the city’s elevated rails for three days. Conductors shooed the female inventor off the rear platform as she tried to listen and observe. Passengers looked askance at the well-dressed woman listening intently to what they simply accepted as the everyday din, her head cocked toward the rails. But after those three days, Walton discovered that the tracks amplified the noise of the train because of the plain wooden supports they ran through.

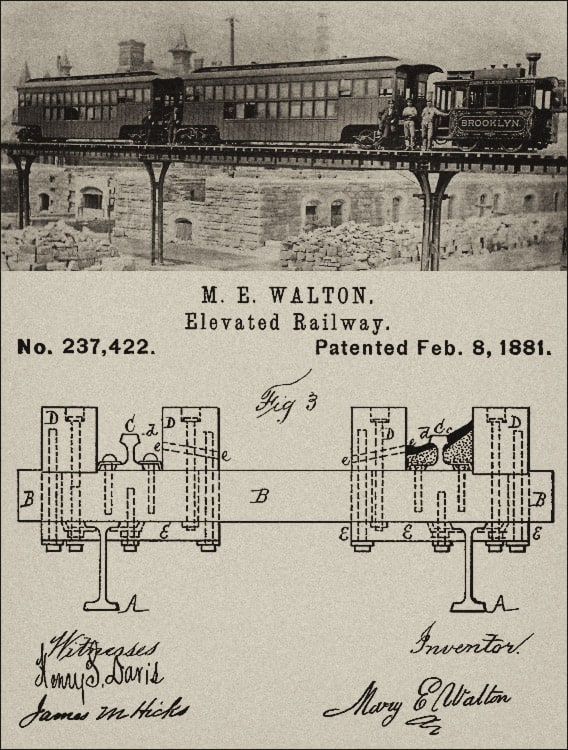

Her Manhattan basement soon became the site of a model railroad she built to experiment with different noise-reduction systems. As a result, she embedded her model rails in a wooden box-like structure that was first painted with tar to weatherproof it, then lined with cotton and filled with sand. Just as her patent for locomotive and other chimneys used water to absorb smoke and noxious fumes, she found that sand best absorbed the vibration and sound from nearby rails.

A full-size version of Walton’s device was built to fit the elevated train. And after a series of successful trials fitting her box-like system under the supports of the city’s elevated tracks, Walton was granted U.S. Patent #327,422 in 1881.

A ‘royalty forever’ on her patent

She immediately sold the rights to New York City’s Metropolitan Railroad; before long, Walton’s anti-noise pollution system had become a staple of other elevated rail companies. While the benefit to Manhattanites and their quality of life was considerable, Walton didn’t do too badly either — she received $10,000 and a “royalty forever” for going where no man had been able to go with her sound-dampening invention.

Mary Elizabeth Walton was hailed as a hero. As the Woman’s Journal put it twenty years later, “The most noted machinists and inventors of the century had given their attention to the subject without being able to provide a solution when, lo, a woman’s brain did the work.”

Unfortunately, documentation about Mary Walton’s early years is scarce. But a statement made in 1884 and published in Lexington, KY’s, Weekly Transcript holds a rare clue: “My father had no sons, and believed in educating his daughters. He spared no pains or expense to this end.”

But in an era when married women’s legal rights were nonexistent, when their property reverted to and became the property of their husbands, Walton’s sense of humor, feminist leanings and a downright stubborn streak emerge in a comment about one of her devices that eventually, in her words, “proved to be a valuable invention.”

‘No man in it’

Her husband, tickled by his wife’s talent and ingenuity, showed her prototype to a male friend — who promptly stole the idea, patented it, and reaped the benefits. So when Walton developed her idea to trap airborne pollutants, she “determined there should be no man in it.”

And later, when her son suggested she patent her railroad sound-deadening idea in his name, lest, God forbid, people cast her as a “strong-minded woman,” Walton is quoted as telling him, “Make your own inventions, and have your name put to them.”

Today Mary Elizabeth Walton is recognized throughout the educational community as a STEM female role model. Intelligent, talented and creative, she saw a problem, got to work, and solved it.

Thank you so much

Thank you