You probably don’t know her name. But one female economist has been feeding America for decades. From the “Penny Milk Program” of the 1940s to today’s Supplemental Nutrition and Assistance Program (SNAP), Isabelle Kelley made it her mission to see that the poorest of Americans did not go to bed hungry.

Isabelle Kelley was born and raised in Connecticut. A product of the public schools, she enrolled at the University of Connecticut, where a counselor steered her toward a program offering advanced physics and basic economics. It was, to hear Kelley tell it, “the only time I was conscious of being a girl.”

The only freshman in her physics class, and the only female, she wanted to quit because she thought the course was “too complicated.” Nevertheless, she persisted, becoming the first woman to receive a degree in agricultural economics from the University of Connecticut in 1938.

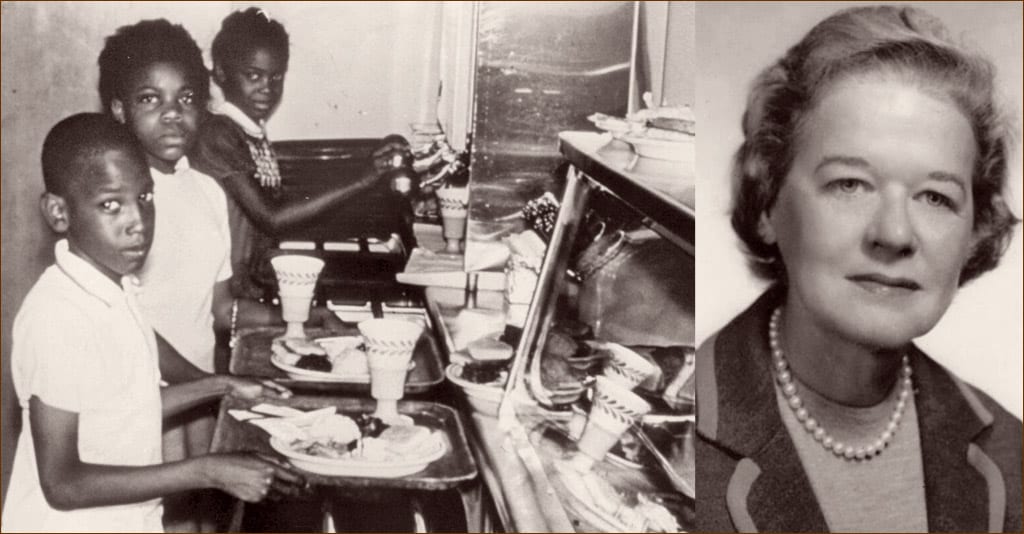

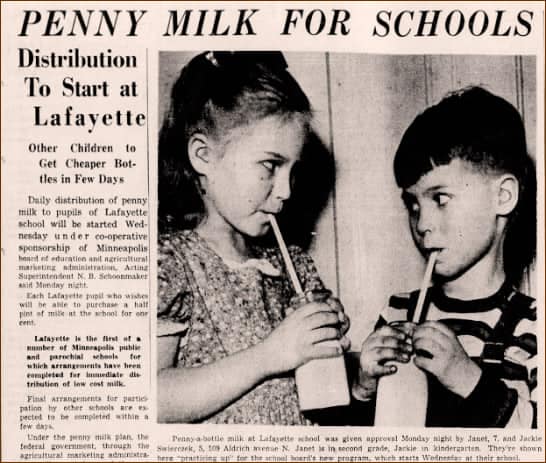

Penny Milk Program

But Kelley didn’t stop there. After taking part in a survey of farm workers in the Connecticut River Valley, she got her master’s degree in economics at Iowa State University before joining the Department of Agriculture as an economist in 1940, where she ran the “Penny Milk Program,” providing half pints of milk to students for a penny — one of the first federal programs to supplement the nutritional needs of America’s schoolchildren.

Despite America’s reputation as the breadbasket of the world, many American families lacked proper nutrition during World War II, when harvests were being shipped overseas to feed our military and rationing essentials like bread, cheese, meat and sugar became the law of the land. It fell to Kelley to develop rationing requirements and represent the interests of Americans here at home in a competitive wartime market.

Minority Discrimination

She was a dedicated civil servant when leadership opportunities for women in government were few and far between. But she knew full well that, as a woman, she had to “be better and work harder than men to get a comparable grade.” Still, any gender discrimination she experienced, “paled into insignificance when I saw the discrimination practiced against minority groups,” mainly Black people. She realized the importance of her role in 1946, when she was invited to a debate in the House of Representatives over the National School Lunch Act, introduced in response to rising concerns over childhood hunger.

Kelley remembered a heated exchange as Harlem congressman Adam Clayton Powell Jr. proposed and fought for an amendment to a bill to withhold federal funding for schools or states that practiced discrimination in operating the lunch program. The amendment passed, one of the first early challenges to segregation that Powell, a Democrat, would introduce. “It was then I fell in love with the legislative process,” Kelley said. President Harry S. Truman signed the act into law in June of 1946, saying, “no nation is any healthier than its children.” The National School Lunch Program is still available in schools across America.

Launching Food Stamps

Kelley’s role in feeding America expanded in the early 1960s, as government became more involved in social welfare policy under President Kennedy’s “New Frontier.” The day after his inauguration, Kennedy’s first executive order expanded existing food distribution programs for needy families — a promise he made in West Virginia during his campaign. The Agriculture Department named Kelley to a four-person task force charged with designing and implementing a food stamp program.

Mr. and Mrs. Alderson Muncy of West Virginia were the first food stamp recipients in May 1961, using $95 in stamps to feed their 15-person household. Their first purchase? A can of pork and beans. By 1964, the pilot programs had grown from 8 areas to 43, in 22 states, with 380,000 participants.

A pilot program launched in eight of America’s poorest counties became the Food Stamp Act of 1964 when it was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson, who called it “a realistic and responsible step toward the fuller and wiser use of our agricultural abundance.” Kelley became the first director of the Food Stamp Division a year later, rising through the ranks of the Department when there were few women in leadership roles. Within five years, the program was serving six million Americans, with a budget in the hundreds of millions of dollars.

Armed with a keen grasp of policy and the inner workings of government, Kelley also used her position to provide career opportunities for women and people of color, providing them with a good working environment.

SNAP Program

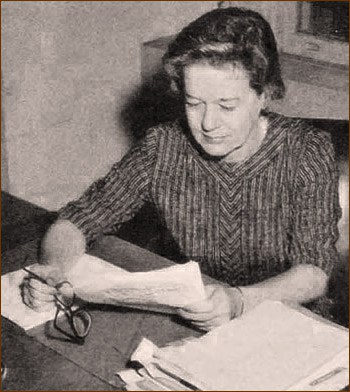

After a 33-year career with the Department of Agriculture, Isabelle Kelley retired in 1973. She lectured at Georgetown University Graduate School, was a frequent speaker at USDA events, and continued to mentor USDA employees for many years. She made sure to stay involved with the department when it came to assuring continued funding for the Food Stamp Program now known as SNAP.

And in 1987 she was one of 38 women interviewed as part of an oral history project conducted by Harvard’s Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America. It’s goal was to document the memoirs of women who had achieved positions of high rank in the federal government in the mid-20th century.

USDA Hall of Heros

After a short illness, Isabelle Kelley died in Bethesda, Maryland, in 1997 at the age of 80. She was inducted posthumously into the USDA Hall of Heroes in 2011, honored for having made significant contributions to the agency and its mission of leadership on food, agriculture and natural resources based on public policy and science.

Connecticut Congresswoman Rosa DeLauro spoke at the induction ceremony, citing Kelley as “a woman who knew the power of the federal government to make a difference for people.” Throughout six presidential administrations, from Franklin Roosevelt to Richard Nixon, she was the architect of America’s federal food assistance and nutrition programs. Her programs remain embattled to this day, subject to debates centered on budget cuts, tightening eligibility requirements and criticisms over equity. But few can argue with the difference Isabelle Kelley has made to the lives of millions.