Hammonton, New Jersey, is the Blueberry Capital of the Garden State. Once upon a time, sixteen-year-old Kellyanne Fitzpatrick Conway was crowned Blueberry Pageant Princess. And we all know Fats Domino found his thrill on Blueberry Hill. But were it not for Elizabeth Coleman White, none of that would have happened.

A true daughter of the Pines, White introduced the first cultivated blueberry crop to New Jersey and the world. Along the way, she transformed the local economy, and created a delicious industry that spread around the globe — in 2016, the United States alone produced 690 million pounds of blueberries.

So while Kellyanne Conway may once have been dubbed Blueberry Pageant Princess, she’s got nothing on Elizabeth Coleman White, rightfully known as the “Blueberry Queen.”

Quaker Cranberry famers

The eldest of four daughters born into a well-to-do Quaker family of farmers who specialized in growing cranberries — her father wrote the definitive book on “Cranberry Culture” in 1870 — White spent her early years near Smithville before the family settled in nearby New Lisbon. Formally educated at Friends Central School in Philadelphia, she graduated in 1890. The only one of her sisters to take an interest in the family business, she was sometimes described as the son her father never had. It was Elizabeth who, as a girl, accompanied him into the fields. As she later recalled, “I always shirked the woman’s job of serving meals and instead stuck close to my father’s side, eager to hear all the cranberry talk.”

By 1893, at age 22, all that talk paid off when she started working in the bogs as a “bushel man,” tasked with counting the pickers’ harvests on tally tickets they later redeemed for cash and supplies. But with her hands-on experience and a passion for the Jersey Pines she inherited from her father, it didn’t take long for her to become his business confidante.

A bold experiment

The family business, officially named J. J. White, Inc., spread over 3,000 acres but was simply known to the locals as White’s Bog. Eventually, Elizabeth approached her father with an idea that had long been on her mind — why not grow blueberries in the unused land between their cranberry bogs?

Blueberries ripened earlier than cranberries, so their July harvest would nicely complement September’s cranberry yield. She had been studying the little blue berries known as “swamp huckleberries” that grew wild in the sandy soil of the Pine Barrens, and knew the local Pineys ate them and sold them by the quart to Philadelphia’s bustling markets every summer. But nobody had succeeded in their commercial cultivation. Common knowledge held they were simply not a profitable crop in the Garden State. But that didn’t deter Elizabeth White.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]See New York Times Guide to Jersey Pinelands Pick-Your-Own Blueberry Farms[/perfectpullquote]

Chief U.S. Botanist

In 1910, when she was 39 years old, she read “Experiments in Blueberry Culture,” by Dr. Frederick V. Colville, chief botanist for the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, and convinced her father they should invite him to White’s Bog. She wrote to Dr. Colville with a proposition: The J. J. White company would provide unused land between their cranberry bogs in return for the USDA planting an experimental plot of blueberries. Dr. Colville knew the science of plants, but Elizabeth White knew the Pines, knew how to work the soil and run the business.

Working mainly in a lab in Washington, D.C., Colville provided his research on blueberry cultivation, visiting Whitesbog from time to time, while White supplied her practical knowledge and ability to recruit woodsmen to search out the best swamp huckleberry bushes.

“Miss Lizzie,” as she was known, paid local Pineys $1 to $3 for bushes with big, juicy berries measuring at least 5/8″.

Selling berries and bushes

Each bush was tagged by the man who found it. Once berry season ended, the men led White back to their bushes and uprooted them so Dr. Colville could apply the results of his research to hybridize and propagate them. Over a period of five-years, at least 100 different bushes were identified, dug up and cut into grafts that eventually produced hundreds of other plants.

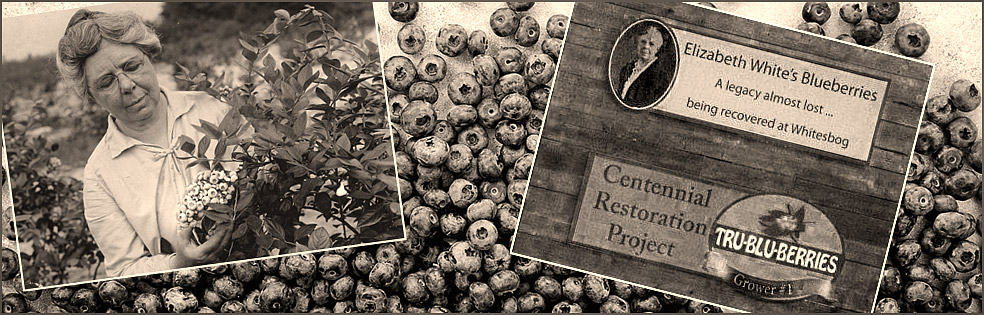

By 1916, White and Colville had successfully cultivated and brought to market a viable blueberry crop in addition to creating a whole new business selling blueberry bushes. Their first commercial crop of blueberries was sold under the name Tru-Blu-Berries. At the peak of production, Whitesbog cultivated 90 acres of blueberries, which translated into 20,000 barrels a year. To show off the fruits of their labors, Elizabeth Coleman White became the first to use cellophane in packaging blueberries, protecting the fruit while enticing customers with a view of the bright, plump berries.

Historic Whitesbog village

While Elizabeth Coleman White called Whitesbog home, it was also a company town. Forty-one permanent employees and their families rented homes in Whitesbog Village. There was a general store, post office, schoolhouse and paymaster’s office, along with all the buildings needed to process cranberries — a warehouse for packing and storage, a barrel factory, barrel storage warehouse and a water tower often that doubled as a lookout for forest fires in the Pine Barrens.

But White’s horticultural interests weren’t limited to berries. A respected agriculturalist, she made a serious study of plants that were native to the New Jersey Pine Barrens and promoted their use in home landscapes, often inviting groups to tour her gardens at Suningive, the home she built at Whitesbog in 1923. She also experimented with the American holly, and is widely credited with helping rescue this beloved plant from obscurity.

White House appointment

As a founder of the Blueberry Growers Cooperative Association and the first female member and president of the American Cranberry Growers Association, White worked tirelessly to improve the lives of South Jersey’s migrant workers on whom its seasonal crops depended in the areas of housing, sanitation and their children’s education. In 1931, President Herbert Hoover appointed Elizabeth Coleman White to his Migrant Farm Worker Housing Committee.

In addition to its permanent workers, Whitesbog also hired Italian immigrants, many who lived in South Philadelphia, for peak seasonal work from early September to mid-October. But as progress and improvements in harvesting technology eventually led to the need for fewer employees, the population of Whitesbog Village decreased. In 1967, the New Jersey Environmental Protection Department purchased Whitesbog as part of the Lebanon State Forest (now known as Brendan T. Byrne State Forest).

Elizabeth Coleman White died of cancer in November of 1954 at the age of 83. Her ashes were spread across the bogs and fields in the New Jersey Pine Barrens she loved.

Blueberry Queen of the Jersey Pines

Thirty-four years earlier, she had boldly assured the American Pomological Society “blueberry culture has a great future … In a few years it will yield large revenues from thousands of acres that today are wasteland.” She was right. Today more than half a million acres in the United States alone are dedicated to growing blueberries. And “Blueberry Queen” Elizabeth Coleman White’s Whitesbog is recognized as the birthplace of the modern blueberry.

Love this story….I had read about her before but it has been a while….really appreciate this reminder.