That Bessie Blount Griffin became a inventor, physical therapist, business women, forensics expert and social activist before she passed on in 2009 is all the more remarkable, given that she was born in an era before women — particularly African American women — could expect opportunities in any one of the multiple fields in which she ultimately succeeded. Her life is a lesson in tenacity, irrepressible creativity and a deep sense of empathy for the people and causes she helped.

Were it not for a schoolteacher, a ruler and some sore knuckles, Bessie Blount’s life would have taken a very different turn. Born in 1914 in Hickory, VA, Blount attended a one-room school built by African Americans after the Civil War to educate the children of freedmen, former slaves and Native Americans. She was among the 10% of Americans born left-handed which, back then, was considered an affliction to be corrected. And so it was that every time Blount picked up a pencil and began to write with her left hand, the teacher gave her a sharp rap on the knuckles.

In response, young Bessie figured if she couldn’t use her left hand, she’d teach herself to write with her right … and with a pencil held between her teeth, and even with her feet. It was a learning experience she would never forget, and one that would help shape her life.

Father’s war injuries

By the time Blount completed sixth grade, she had exhausted the academic resources for black children in her small community. After her father’s death due to injuries from World War I, she and her mother moved to New Jersey in the 1920s, where Blount continued her studies and earned the equivalent of a GED. She went on to complete a nurse’s training program at Community Kennedy Memorial Hospital in Newark, NJ — a hospital run by and for African Americans that later became the state’s first integrated hospital. She then shifted her focus to study physical therapy and rehabilitation, first at Panzer College of Physical Education and Hygiene (eventually part of Montclair State College) and Union Junior College, completing her formal training in Chicago. By 1951 she was living in Newark, working as a physical therapist, and teaching physiotherapy at the Bronx Hospital in New York City.

Treating injured war veterans

After World War II, she found her true calling, working to rehabilitate the paralyzed and limbless veterans who crowded America’s V.A. hospitals in the early post-war years. Blount was so good at rehab, her colleagues called her Wonder Woman. Falling back on her self-taught skills from that one-room schoolhouse, she even taught some of her armless vets to type with their feet.

[perfectpullquote align=”right” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]She exhibited a deep sensitivity to the problems of the disabled, and to their need for dignity, self esteem and self-reliance.[/perfectpullquote]

She exhibited such deep sensitivity to the problems of the disabled, and to their need for dignity, self esteem and self-reliance, that when a doctor told her, “If you really want to do something for these boys, why don’t you make something by which they can feed themselves?” Blount decided to do just that.

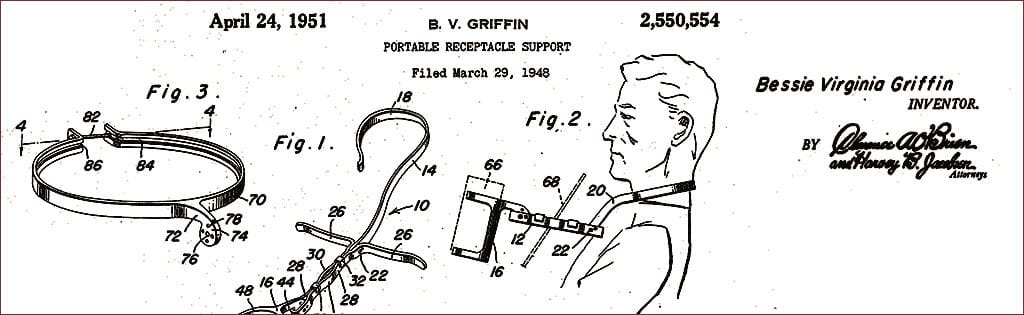

Working in the kitchen of her apartment in her time off with just “a dream and the help of God,” Blount spent five years and $3,000 of her own money to design and produce a self-feeding device that could be used seated or lying in bed. The only help a patient required was with the initial setup of the apparatus. Blount later simplified her invention to fit into a brace worn around a person’s neck, accomplishing the same function.

1951 patent award

The self-feeding device dispensed bite-sized portions of food down a tube to a spoon-shaped mouthpiece, shutting off automatically after each bite to avoid choking or overfeeding. The user signaled for another portion by biting down on a switch. With her invention, even quadriplegics or quadruple amputees could feed themselves, as long as they could bite and swallow. In April of 1951, she was granted Patent #2,550,554 in the name Bessie Blount Griffin, her married name.

While still working on her device, Blount repeatedly tried to interest the Veterans Administration, but got nowhere until her Congressman made her an appointment with the system’s chief medical director. Despite earning praise from the physician who had first inspired her, as well as the retired director of the American College of Surgeons and other hospital authorities, Blount was summarily shut down by the head of the V.A., who called her invention impractical, reminding her the V.A. had enough nurses and aides to give its veterans the personal care they needed.

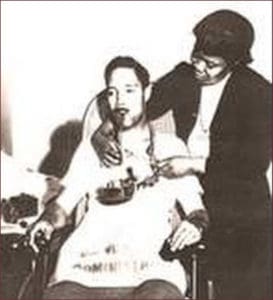

Early Philadelphia TV

Undaunted, Blount tried to market her invention herself by appearing on a Philadelphia TV show called “The Big Idea,” a 30-minute program that aired from December of 1952 to October of 1953. Blount demonstrated her device to an American audience fascinated with the new medium of television, becoming the first woman and first African American to appear on the program.

When, despite her best efforts, there were no takers, Blount offered the patent rights to the French Government for their use in military hospitals, proudly signing the agreement at the French Embassy in 1952. Her press statement said she felt she had contributed to the progress of her people by “proving that a black woman can invent something for the benefit of humankind.”

But Bessie Blount wasn’t done inventing. In the 1960s she re-invented herself. While working as a nurse in New Jersey, she began studying handwriting, noting how our writing movements react to disease, stress, medications, stimulants and our physical environment. Eventually, after she published a technical paper on “Medical Graphology,” law enforcement agencies in Vineland, NJ, and Norfolk, VA, took notice. By the mid-1970s Blount was employed as the chief document examiner for Virginia’s Portsmouth Police Department.

In 1977, at age 63, Blount became the first American woman sent overseas to train in the advanced honors program at the Document Division of the Metropolitan Police Forensic Science Laboratory in London, England (better known as Scotland Yard), where she earned the affectionate nickname “Mama Bessie.” She was the first African-American woman given such an honor.

Expert forensic witness

Returning home, Blount started her own business, using her forensic training to testify as an expert witness in high-profile court cases involving evidentiary handwriting samples. As a hobby, she also began examining documents relating to slavery, the Civil War and Native American treaties to determine their authenticity — the basis for a consulting business Blount ran into the 1990s until the age of 83.

In 2005 Bessie Blount’s name was added to the list of Virginia Women in History. Two years later, she was inducted into New Jersey’s Cumberland County Black Hall of Fame and honored with the state’s Joint Legislative Commendation. She was a member and associate of the International Association of Forensic Sciences (IAFS), the National Organization of Black Law Enforcement Executives (NOBLE), and the Montreal Rehabilitation Institute.

Strong advocate in New Jersey

Freely donating her time and talents to the Vineland NAACP, Camden Community College and the Vineland’s Creative Achievement Academy, Bessie Blount was a strong advocate for children, veterans, animals, and women’s and human rights throughout much of her life.

She died at her home in Newfield, NJ, in December 2009 at the age of 95, and is buried at Gouldtown Memorial Park in Cumberland County, New Jersey.

Amazing!