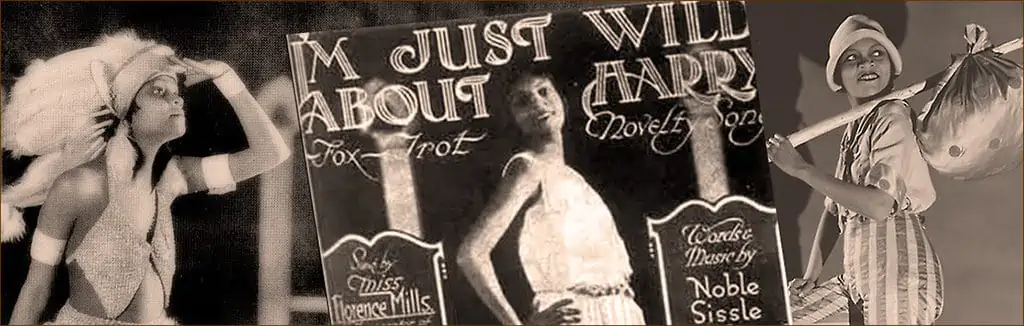

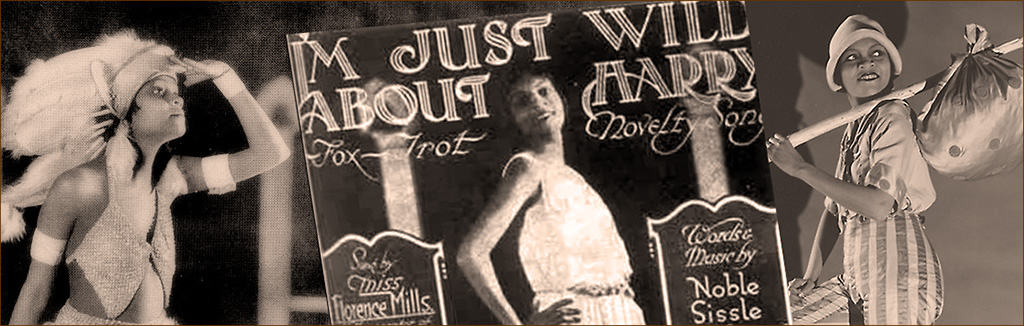

It was the Roaring Twenties, the anything-goes Jazz Age, when Florence Mills made her mark in American history. Known as the “Queen of Happiness,” she was a cabaret singer, dancer and comedienne known for her effervescent stage presence, unique birdlike voice, wide-eyed beauty and slicked bobbed hair imitated by women on both sides of the Atlantic.

One of the most outstanding black women in musical comedy in the 1920s and one of the most popular personalities of the Harlem Renaissance — a golden age of black culture that brought us legendary entertainers like Cab Calloway, Louis Armstrong and Bessie Smith — she was a trailblazer who paved the way for every African-American female international superstar who would follow.

From “Baby Florence” to Broadway

Born into poverty in 1896 to freed parents, she was the seventh of eight children, five of whom died young. With a natural flair for song and dance, she appeared onstage as “Baby Florence” at about five. As a teenager, her family lived in Harlem, where Florence and two sisters created their own vaudeville act. Performing as the Mills Sisters, they toured the circuit of black clubs along the east coast to help support the family.

When her sisters left the act in 1916, Mills joined a traveling black revue, The Tennessee Ten, where she met the man who would become her husband and lifelong partner, Ulysses “Slow Kid” Thompson, best known for his acrobatic tap and “rubberlegs” dancing. It was Thompson who urged Florence to audition to replace the lead in a musical comedy called Shuffle Along.

Breaking Racial Barriers

The show’s creators, skeptical at first as a tiny, frail-looking, rather demure woman walked on stage, quickly changed their minds as Mills knocked their socks off with her uninhibited dance, high voice and flair for comedy. The first all-black show to command full Broadway prices, Shuffle Along broke from the mold of blackface minstrelsy, bringing authentic black artists to the American stage and, according to Langston Hughes, igniting the Harlem Renaissance. In the process, it made Mills an overnight success.

As it broke box office records, Shuffle Along destroyed racial stereotypes. For the first time, black audiences sat in orchestra seats instead of being relegated to the back balcony; it featured the first sophisticated African-American love story; and paved the way for audience acceptance of black performers in other than burlesque roles.

When, after 500 performances, Shuffle Along closed to go on the road, Mills opted to stay in New York as part of Plantation Revue, a show that drew white audiences to an entirely black-themed work. As Richard Newman, chair of Harvard’s Afro-American Studies Department and author of Notable Black American Women, wrote, “There was real appreciation for the authenticity of black song and dance with the realization that Negro portrayals by blackface performers like Al Jolson and Eddie Cantor were only imitations of the real thing.”

International Superstardom

Mills had already gained critical acclaim overseas from Shuffle Along by 1923, when showman Charles B. “Cockie” Cochran was ready to take a mixed-race show called Dover Street to Dixie to the London Pavilion in Piccadilly Circus and added Mills to the cast. Cochran described Mills’ opening night performance that seemed to mesmerize the London audience: “She owns the house — no audience in the world can resist her.”

Ziegfeld Follies and Duke Ellington

Returning to New York, Mills was approached by Florenz Ziegfeld, the most important producer in the history of Broadway musicals, who offered her a major role in his Ziegfeld Follies. But Mills, who always sought to use her status to highlight the racial strife of the 1920s, turned him down to create a rival show starring an all-black cast. Dixie to Broadway opened in 1924 at the same time a young man named Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington was launching his career as a composer. Four years later, Ellington renamed one of his signature songs “Black Beauty” in honor of Mills.

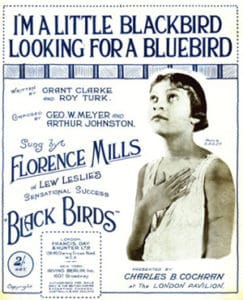

With the successful year-long run of Dixie to Broadway, Florence Mills achieved her goal of creating an all-black revue. Once it closed, producer Lew Leslie cast her as the lead in Blackbirds, starring alongside Bill “Bojangles” Robinson. Blackbirds debuted in 1926 at Harlem’s Alhambra Theatre for a successful six-week run that would be Florence Mills’ final farewell to friends and supporters before Leslie took the show to an extravagant Parisian nightclub/restaurant called Café des Ambassadeurs.

In the summer of 1926, Blackbirds was the most fashionable event of the Paris season, establishing the Ambassadeurs as the most important theater-restaurant in the world. And it was there, according to the press, that “the legendary Florence Mills made her first appearance by emerging out of a birthday cake carried onstage. She was regarded as a bewitching little figure, her dancing always graceful and her singing voice clear and high as she sang ‘I’m a Little Blackbird (Looking for a Bluebird’).”

After Paris, Blackbirds took London by storm when it opened in September at the London Pavilion in Piccadilly Circus where Mills starred in more than 250 performances. The Prince of Wales was said to have seen the show more than 20 times and the press couldn’t get enough of what they called “Blackbirds mania.” Mills had become to London’s smart set what the legendary Josephine Baker was to Paris.

The Final Curtain

In 1927, while touring abroad with Blackbirds, Mills was visibly ill and showed the stress of doing two shows a day plus matinees and the charity work she loved. Told by doctors she was suffering from exhaustion and had to stop performing, she and her husband went to Baden-Baden in Germany for a rest cure. But by the fall they were back in New York where, on October 24, she underwent surgery at New York City’s Hospital for Joint Diseases. But it proved too little, too late. On November 1, 1927, at age 31, Florence Mills, the “Queen of Happiness,” was dead.

The press reported her cause of death as paralytic ileus — most likely a complication of surgery for pelvic tuberculosis with involvement of the bones. Doctors told her husband that even had Florence survived the surgery, her tuberculosis was so far advanced she had little hope of long-term survival.

Thousands attended her funeral at Harlem’s Mother Zion AME Church as an estimated 150,000 mourners lined the streets for the funeral procession. She was laid out wearing white satin, white stockings and little silver slippers. The great Ethel Waters, with whom Mills had performed, was one of her pall bearers. Florence Mills was laid to rest in Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx alongside other musical greats, including Duke Ellington and W. C. “Father of the Blues” Handy.

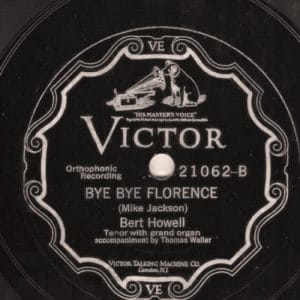

The Little Blackbird and Victor Records

The story of Florence Mills has a local twist that perhaps explains why she is so little known. Though she had a unique voice described by contemporaries as “full of bubbling, bell-like bird tones,” “a rather magical thing,” “silvery,” and “funny little sounds that flutter out like sparrows from an inexhaustible nest,” not a single recording of her voice survives.

Never heard of her before. Thanks for bringing her back to life. Wish I could hear her voice.