Frances Densmore first heard the sound of a Dakota Sioux drum as a child. “I fell asleep night after night to the throb of that drum,” she later recalled. But while others heard the same sound and quickly forgot it, Frances Densmore followed that drum beat for the rest of her life.

Born in a converted schoolhouse on the banks of the upper Mississippi River Valley in Red Wing, Minnesota, overlooking Trenton Island along Wisconsin’s shore, she could see the flickering campfires of Dakota hunting parties on the island and hear their drums.

Her mother taught her to play harmony on the piano long before she embarked on the most rigorous musical training program then offered in the United States. In 1884, at age 17, she went to Ohio’s Oberlin College Conservatory of Music, studying piano, organ and harmony.

Harvard studies

She went to Boston after graduation, continuing her studies with Harvard professor and composer John K. Paine, first professor of music at an American university, before returning to Minnesota to teach piano.

She traced her serious interest in Native American music to her time in Boston, where she discovered Alice C. Fletcher’s work on the music and customs of the Omaha tribe. Her book, A Study of Omaha Music, published in 1893, inspired Densmore’s lifelong study of Native American music and customs.

Her first up-close-and-personal exposure to Native American music came at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, where she “heard Indians sing, saw them dance and heard them yell, and was scared almost to death.” Two years later, Densmore gave her first lectures on Indian music, illustrated with Omaha songs, that drew the attention of local press. The Chicago Times Herald wrote, “far from being the crude tom-tom pounding and shouting which palefaces think it, Indian music expresses rare color and originality and even has musical value in the higher sense.” Closer to home, the St. Paul Pioneer Press noted “how the weird, original music of the American Indians reveals an entirely new phase of their character. Heretofore, very little attention has been paid to them in this respect.”

Their characterization of Native American music as nothing more than “crude tom-tom pounding and shouting” wasn’t surprising, considering Densmore was learning, recording and transcribing their music at a time when white America was systemically stripping away tribal culture in efforts best captured by the guiding principle and mission behind Pennsylvania’s Carlisle Indian Industrial School and those like it in the early 1900s: “Kill the Indian and save the man.”

Canadian border Chippewa village

By 1905, Densmore was conducting her own field studies, traveling with her sister, Margaret. To say it was unusual for two unmarried, 30-something white women to trek to a remote Chippewa village near the Canadian border led by Indian guides they had just met is an understatement. And it was no easy trek.

With no roads along Lake Superior’s North Shore, they took a boat from Duluth to Grand Marais, then hitched a ride on a logging tug and a sailboat to reach their destination. When they finally arrived and made contact, Densmore explained her interest in their music to the Grand Medicine man, specifically asking about his hunting songs. She quickly realized how much she had to learn when, with a quizzical smile, he replied he never sang when he went hunting, just kept very still, took aim and shot the game.

After making proper arrangements about price (performers were paid 25¢ per song) and the length of the session, the Chippewa agreed to hold a ceremony that night, its rituals and music providing Densmore with enough material for two short articles and a number of magic lantern (precursor of the 20th-century slide projector) photo slides for her lectures. Densmore described the songs as “full of wild beauty” as the Grand Medicine man sang one after another, “beating the tom-tom with the curved stick in his right hand and shaking steadily the Grand Medicine rattle in his left.”

Smithsonial Institution

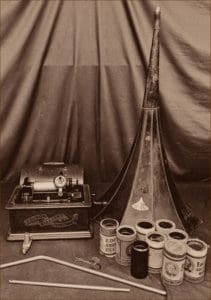

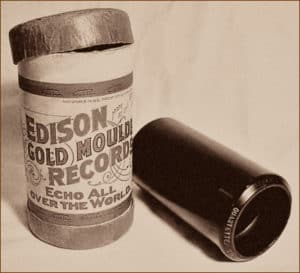

Densmore wrote to the Smithsonian Institution’s Bureau of American Ethnology (BAE) in 1907, describing her work and soliciting support for her field research to record Native American songs before they disappeared forever. Frederick Hodge, bureau chief, responded with a grant of $150, with which she bought an Edison cylinder recording machine with a steel “morning glory” horn that served as both microphone and speaker — the same type of machine she would use in the field for the next 30 years. She promptly returned to the Chippewa village, where the medicine man was persuaded to sing the same songs, this time recorded for posterity.

The following year, Densmore was called to Washington to report on her work. After presenting her recordings and details of the Chippewa Grand Medicine ceremony, the bureau paid her $300 for the first investigation of native music supported by the BAE. Later that year, Densmore lectured before The Anthropological Society of Washington, where Alice Fletcher was in the audience. She finally got to meet the woman who was her greatest inspiration.

Year after year, Densmore spent summers in the field, traveling to remote reservations by train, automobile, wagon and canoe, while hauling a lot of bulky equipment: her phonograph, a typewriter, camera and camera gear, and all her necessary supplies. She recorded her wax cylinders and filled notebook after notebook until winter forced her back home to Red Wing, where her days were spent sorting and interpreting the material.

Collecting artifacts as well as songs

But it wasn’t just about the music. Densmore knew she needed to do more than just record songs. Usually working with interpreters who spoke English as well as tribal languages, she wanted to know why they were written, when they were sung and who traditionally sang them so she could fully understand their meaning. And to add depth to her written transcripts, she collected objects that related to the music — the instruments played and any herbs, materials or artifacts associated with the songs.

She recorded songs from ceremonies, war, games, dances and other tribal rituals; songs used in treating the sick and songs of the Ghost Dance and Peyote Cult, some believed to be 200 years old. And she recorded songs of the Lakota Sioux Sun Dance. Outlawed by the Bureau of Indian Affairs on all reservations, it was one of their most sacred ceremonies, during which an offering was made to the spirit Wakan Tanka. Though the Lakota were forbidden to perform the ceremony itself, they described it to Densmore before singing the sacred songs.

Over the years, Frances Densmore worked with the Chippewa, the Mandan, Hidatsa and Sioux; the northern Pawnee of Oklahoma, the Papago of Arizona and Indians of Washington, British Columbia, the Winnebago and the Menominee of Wisconsin; the Pueblo of the southwest, the Seminoles in Florida and even the Kuna tribes of Panama. Her work was often published in the journal American Anthropologist. She authored Indians and Their Music in 1926; and between 1910 and 1957, published 14 book-length pieces for the Smithsonian, each describing the music and repertoires of a different Native American group.

Bureau of American Ethnology

Densmore worked tirelessly for the Bureau of American Ethnology from 1907 until 1933, when the Great Depression brought hard times to America and the BAE could no longer fund her work. But in 1939, when the bureau resumed its support, a 72-year-old Densmore returned to the field with all the enthusiasm that had characterized her earlier work.

Eventually, the BAE could no longer store or properly preserve the Densmore collection. A private gift to the U.S. government of $30,000 allowed for the transfer of her wax cylinders, artifacts and transcripts from the Smithsonian to the National Archives, only to find its recording/duplicating facilities weren’t up to the task. So, after considerable study, the collection was transferred to the Music Division/Recording Laboratory of the Library of Congress.

The Library first had to purchase new equipment and design and build machines to play cylinders as well as discs. With everything in place, Densmore’s cylinders were copied onto two sets of 16″ discs. Money from a private donor allowed the Library to hire Densmore to catalog her collection. So, at age 75, her field work now behind her, Frances Densmore spent the next 15 years seeing that the 2,500 delicate wax recordings were safely preserved in the Library of Congress.

The work vs. the person

Her final years were devoted to retyping boxes of field notes, articles and speeches, painstakingly preparing her public historical record while destroying any trace of who Frances Densmore, the woman, was. In fact, her will specifically ordered that all letters, notebooks and manuscripts stored in her desk be burned; she had already distributed the “professional” Frances Densmore as reflected by her body of work to various archives.

Densmore began her studies of Native American music at age 26, pursuing it until her death at age 90. She recorded songs in America’s most remote and unknown places, capturing as much material as possible before the oldest singers died, taking their knowledge with them. As she wrote to one correspondent, “there is more to the preservation of Indian songs than winding a phonograph.”

At the age of 87, in 1954, Frances Densmore gave a series of seminars on Indian music at the University of Florida in Gainesville. Three years later, she died of pneumonia and heart failure at home in Red Wing, Minnesota, just two weeks after her 90th birthday. She is buried in Oakwood Cemetery.

Remarkably productive career

Over the course of a remarkable career, through more than 20 books, 200 articles and some 2,500 Graphophone recordings, Frances Densmore preserved cultural traditions that would otherwise have been lost. Her collection is now considered a national treasure in the recorded collection of the Library of Congress. And her work has recently been revived using more sophisticated sound equipment, making it more useful to those who study the songs today.

Thanks to her, young Native Americans can reconstruct the ways of their ancestors. Every summer, dozens of pow-wows recreate their colorful dances and songs on reservations across America. And every day, traditional Native Americans play their drums, flutes and rattles, lifting their voices as the ancestors once did on the prairies and in the deep forests Frances Densmore once traveled.

Despite her lifelong dedication to collecting and preserving Native American music, Frances Densmore was, after all, a product of her time. Her attitude toward American Indians was typical for a white, 19th-century, Christian woman — condescending and, by today’s standards, decidedly racist. She initially held an idealized opinion of them. But after 40 years of field work, she almost seemed bitter that “her” Indians never willingly assimilated to become part of America’s melting pot. She, like many ethnologists of her time, and like the leaders of schools like the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, believed native culture would — and should– be beaten down in America’s determined march of progress. During her decades of research, she said, “I never let them criticize the government nor the white race, nor come across with any sob-stuff about the way they had been treated as a race.”

HELLO

and very beautifully and sensitively written. I know a bit about Frances as

my Maclaren/ Ingersoll family in Minnesota is related to her , once or twice removed.

For many years I have collected information in articles and books

about her and her works about the Ojibway culture and their medicinal

plants.

My family is in St. Paul, Minnesota and I live in Cambridge ,Ma. and visit

them every summer.

Thanks for writing so well about her.

and best wishes to you.

Judy Summersby

cl771@aol.com

I grabbed a copy of her book on Sioux music- do you know if there is anywhere online to hear the original wax recordings?

Thank You!!

All I can say is thank you.