You might not know her name, but Charlotta Spears Bass was a major badass. She fought the Ku Klux Klan and won. Was the first black woman to run for vice president. And, at the ripe old age of 91, was under surveillance by the FBI.

Birth of a journalist

Born in Sumter, South Carolina, Charlotta Spears made a name for herself as a civil rights activist and crusading journalist. To escape Jim Crow, she moved to Rhode Island, landing a job selling subscriptions to the Providence Watchman, a black-owned newspaper. For 10 years, she made it a point to learn everything she could about the newspaper business.

When the harsh climate played havoc with her arthritis, she moved to Southern California, interviewing in 1910 with John Neimore, founder/publisher of the California Owl. California’s oldest black newspaper, The Owl was founded in 1879 to provide newly-arrived black settlers with news on housing, jobs and other issues affecting their lives. Spears was hired at $5/week to sell subscriptions and serve as Neimore’s Gal Friday.

Recognizing her value to his paper, two years later, when he became ill, he asked Spears to stay on as editor and keep the paper alive after his death. In late 1912, an experienced Kansas newspaperman named Joseph Bass visited The Owl on a trip west. Spears hired him as editor; a year later they were married.

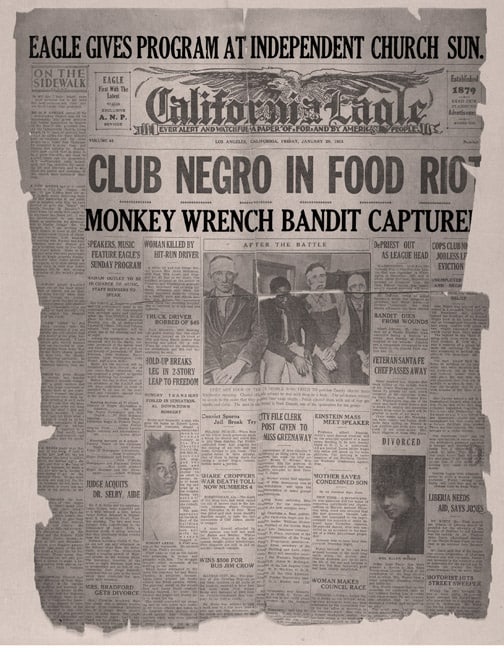

Charlotta Bass bought The Owl for $50 at public auction in 1915, renamed it The California Eagle, and shifted its focus to social and political issues for “patriotically inclined” Americans. With her husband as editor (a position he held until his death in 1934), she served as publisher, reporter, business manager, distributor, printer and janitor, becoming the first African American woman to own and run a newspaper.

Wielding the power of the press

Using the power of the press when it came to taking a stand, she denounced the 1915 movie, “The Birth of a Nation,” for glorifying the Ku Klux Klan and white supremacy. Her editorial voice was echoed by black newspapers throughout America, strengthening her resolve to take on more causes important to African Americans.

The California Eagle became a lightning rod for protest as Bass became the target of hatred and violence. Despite verbal and physical abuse, libel suits, unlawful arrests and death threats, she was relentless in her war against racism. Her husband, fearing for her safety and his own, once said, “Mrs. Bass, one of these days you are going to get me killed,” to which she replied, “Mr. Bass, it will be in a good cause.”

In 1917, Bass took aim at the racist hiring practices of the L.A. Fire Department; while black men could take the civil service exam, the department only hired whites, prompting Bass to write in an editorial, “The city of Los Angeles does not ask the color of a man’s skin when it presents its tax bill.” After a three-month campaign, the city hired its first black fireman.

Her “Don’t Spend Where You Can’t Work” campaign urged blacks to boycott businesses that refused to hire black workers. When the Southern California Telephone Company refused to employ black workers, she convinced black subscribers to cancel their service with letters citing the company’s all-white hiring policy as the reason. When cancellations reached 100, the company relented, hiring its first African American employee.

She fought the city’s campaign to “Keep Neighborhoods White” with restrictive housing covenants and trying to force affluent blacks from their homes. The homeowners, including actresses Hattie McDaniel and Ethel Waters, sued the city. Bass used her newspaper to keep housing discrimination front and center; in 1948 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled racially restricted covenants unconstitutional.

Charlotta Bass vs. the Klan

In 1925, The Eagle obtained and printed a letter to the leader of California’s Ku Klux Klan outlining plans to rid L.A. of its black leaders by involving them in traffic accidents, planting liquor in their cars, and having them unfairly jailed and convicted of drunk driving. The Klan sued Bass for libel, offering to settle if she went on record stating the letter was fraudulent. But Charlotta Spears Bass wasn’t having it. Instead, she fought the charges in an all-white courtroom — and won. In the midst of the trial, eight hooded men confronted her at the office one evening. She calmly responded by pulling a gun from her desk drawer and pointing it at the men, who quickly fled.

The Eagle takes to the air waves

Looking to the future, in 1938 Bass expanded the paper’s voice with a 15-minute “Newspaper of the Air” radio broadcast. Two years later, listeners tuned into “The California Eagle Hour” every Sunday evening on KFVD. Bass finally had the newspaper she had always envisioned — The California Eagle was financially stable, took important editorial stands, and had a circulation of 60,000, making it the largest African American paper on the West Coast.

Civil Rights and Joe McCarthy’s Commie Hunters

With her husband’s sudden death in 1934, Charlotta Spears Bass re-evaluated her life. While the paper remained a priority, she wanted to be more personally involved in community activism. She joined the NAACP, the Urban League, the Civil Rights Congress, the Universal Negro Improvement Association, and founded the National Sojourner for Truth and Justice Club to improve working conditions for black women. Her activities on the national level brought her into contact with people like Paul Robeson and W.E.B. DuBois.

But in the 1940s, with Congress’ House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) hunting down alleged Communists, the FBI, Post Office Department, CIA, State Department and War Department soon took notice. In 1942, FBI agents arrived at The Eagle to interrogate Bass, suggesting her paper was funded by Germany and Japan. From that time forward, agents read each issue of The Eagle, attended Bass’ public speeches, and wrote surveillance reports directly to J. Edgar Hoover in an FBI file that eventually filled 563 pages.

The Post Office also jumped into the fray, investigating The Eagle for subversion, trying to revoke its second-class mailing permit. But the Justice Department weighed in on Bass’ side, calling her reporting legitimate and factual, refusing to revoke the permit.

Bass was called before California’s Joint Fact-Finding Committee on Un-America Activities in 1950. Despite relentless questioning and continuous surveillance, they never found fault with Bass or her newspaper.

A run for Vice President

Worried that all the negative attention was harming circulation, she sold The Eagle and moved to New York City, headquarters of the national Progressive Party. Despite being a lifelong Republican, Bass grew frustrated by the party’s lack of progress toward racial reform, and joined the Progressive Party. Her determination to change American society through politics had proven more powerful than her 40-year investment in journalism.

Charlotta Spears Bass was chosen to run as vice president on the Progressive Party’s ticket in 1952, alongside an Irish attorney named Vincent Hallinan. Their platform supported job security, housing rights, civil rights and an end to the Korean War. It’s slogan: “Let my people go!” Bass had no illusions about winning; the ticket received less than 1% of the vote. But she campaigned tirelessly with the motto, “Win or Lose, We Win by Raising the Issues.”

The strenuous campaign exacerbated her arthritis. On doctors orders, she retired to write her memoirs, published in 1960. But retirement for her meant transforming the garage of her small home into a reading room/community center for voter registration drives, protests against apartheid in South Africa and fighting for prisoners’ rights.

Bass suffered a stroke in 1966 and was moved into a nursing home. And if you’re still not convinced she was a major badass, consider this: As late as 1967, in her nineties, she was still being monitored by the FBI as “potentially dangerous.” She died in 1969 of a cerebral hemorrhage, and was buried alongside her husband in Los Angeles’ Evergreen Cemetery.

Legacy

Charlotta Spears Bass lived a lifetime committed to important issues. From her arrival in California through her final years, she fought for “the light of a better day.” A crusading journalist and political activist, she was at the forefront of major civil rights struggles, using her newspaper to challenge inequality for blacks, workers, women and other minorities.

Charlotta Spears Bass was inducted into the California Newspaper Hall of Fame in December 2017. Although the last issue of The California Eagle was published in July of 1964, her legacy not only lived through America’s civil rights movement of the 1960s and 1970s — it resonates to this day.

Hello,

Is there a reference for this quote?

As late as 1967, in her nineties, she was still being monitored by the FBI as “potentially dangerous.”

Thank you.

Why haven’t we heard more about Charlotte bass before now and why aren’t we talkin about her more especially now ?

Is their a book, transcript, or published work I can buy on Charlotta Spears Bass. I would like to learn more about her.

Rest In Peace Miss Charlotte, you are remembered and Much loved!