Lavinia Ream had three strikes against her. She was young, she was female, and she had friends in high places. But when Congress selected her to sculpt a memorial statue of President Abraham Lincoln in 1866, the 18 year old made history as the first female artist and youngest individual commissioned to create art for the United States Government.

From Frontier to the Nation’s Capitol

Ream was born in 1847 in a Wisconsin frontier town described by the Baraboo Republic newspaper as a land of rolling prairies and “bands of red men in full Indian costume with wampum and jewels worn according to age and rank.” Her father was a government surveyor and map maker, a position that kept the family on the move.

She attended the Academy, a division of Christian College in Columbia — the first women’s college in Missouri and one of the first chartered west of the Mississippi River, where she furthered her interests in art and music. A lifetime student of the harp, some described her as a “child prodigy” with remarkable talent. Her abilities caught the eye of local lawyer, politician and supporter of Christian College, James S. Rollins, who would be a powerful influence in later years.

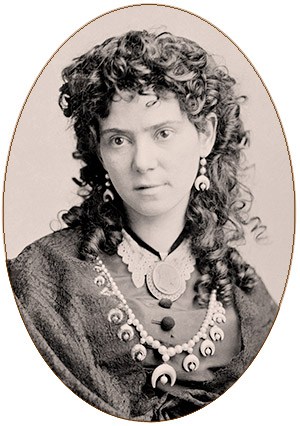

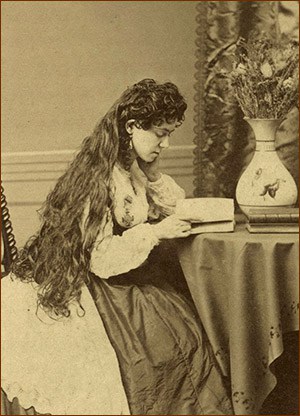

Described as “small, slender and bright-eyed, with a wealth of long curls,” Ream was 14 when the Civil War began. Her family moved to Washington, DC, where, for the first time, she took advantage of the opportunities the war presented women. One of the first women employed by the US Postal Service, she worked as a clerk for $50/month. She also did her part for the war effort, writing letters for the wounded and giving concerts in wartime Washington’s hospitals and churches.

Friends in High Places

She roamed the city in her free time, studying statues in its public spaces. It was then she reconnected with Congressman Rollins. Recalling her interest in art and sculpture, he arranged a visit with Clark Mills, best known for his equestrian statue of Andrew Jackson in Washington’s Lafayette Square. Mills took Ream on as his apprentice in 1864.

She proved to be a gifted sculptor with extraordinary skill in modeling lifelike portraits. After sculpting small medallion-sized likenesses and portrait busts of congressmen and public figures, several of them commissioned her to make a marble bust. They allowed her to pick her subject; and in an audacious move, Ream chose President Abraham Lincoln.

Abraham Lincoln’s sculptor

In late 1864, Lincoln was asked if he would sit for Ream to model a bust of him. Initially resistant, he had to be talked into the project. But when he learned Ream was a struggling young artist with a mid-western background not unlike his own, he agreed. Ream went to the White House, where Lincoln posed for daily half-hour sittings over a period of five months.

Lavinia Ream was the only person to have sculpted a clay model of President Abraham Lincoln from life — an experience that changed her life.

Lobbyist or Public Woman of Questionable Repute?

She was talented, smart and ambitious. But she was also inexperienced. So, after Lincoln’s assassination in 1865, her choice as the sculptor to memorialize the martyred president with a life-size statue for the Capitol kicked up considerable controversy.

Debates raged over her selection out of concern for her inexperience and slanderous accusations that she was a “lobbyist”, or a public woman of questionable reputation. After all, Vinnie Ream was well known for her beauty and conversational skills, fertile ground for such barbs. Senators argued she had “never made a statue in her life,” and that, as a woman, she would be “a complete failure in the execution of this work.”

Nevertheless, she persisted. Her successful completion of the Lincoln bust was proof of her ability. Saying she felt Lincoln’s personality deep within her after modeling the bust, her work was so lifelike she won the commission for the life-size statue over much better-known artists., including her mentor, Clark Mills.

A $10,000 Commission

Lavinia Ream was 18 when Congress selected her, awarding a $10,000 contract — $5,000 to be paid on completion of a full-size plaster model, the rest on completion of the finished marble statue.

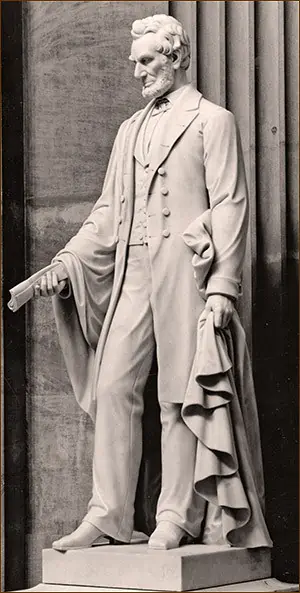

To get the measurements just right, Ream was given the clothing Lincoln had worn the night he was shot. After molding the statue in clay then casting it in plaster, she would use Italian Carrara marble, which was the favorite of Michelangelo.

Ream used the initial $5,000 to travel to Rome with her parents, endorsed by political and military figures in Washington. Armed with a letter of introduction/recommendation from Secretary Seward to American envoys in Europe, and having shipped her life-size plaster cast to Rome, Ream set out to find the purest stone she could.

The family spent two years in Rome where, as was the practice of the time, Ream oversaw the work of skilled Italian stone masons as they carved the marble block, transforming her plaster model into a finished statue. She returned to the United States in late 1870; the unveiling was scheduled for January of 1871. It had taken nearly five years to complete the commission.

Art and How It Defined America

During that time, Ream found herself at the center of a very public and divisive debate over the relationship between art and America’s national identity — classicism vs. realism. Journalist E. G. Waite defined it in Overland Monthly in August of 1871: “One would represent him as a spiritualized, idealized incarnation of a great passion or event; the other would be more intent upon a refined effort of realistic portraiture.”

Until then, American sculpture portrayed its leaders as larger than life and highly idealized. But Ream gave us a Lincoln who was contemplative, emotional and realistic, setting up a conflict of changing perceptions of post-Civil War America and aesthetics. In her work, classical idealism had given way to realism.

In her Personal Recollections of Lincoln, Ream later wrote, “I think history is correct in writing Lincoln as the man of sorrow. The one great, lasting impression I have always carried of Lincoln was that of unfathomable sorrow, and it was this that I tried to put into my statue.”

Underlying that lofty debate was Ream herself. Once again, her character, her work and her sex became targets of senators, a snarky press and society gossips. To some, she was a self-taught sculptor and daughter of the frontier who proved, as had Lincoln, you could succeed in America without privilege and social refinement. To others, she was an opportunist who used her looks to manipulate powerful middle-aged men to secure patronage for her art.

Unveiling

It was snowing in Washington, DC, in January 1871 when a drape was pulled from a life-size statue of Abraham Lincoln in the U.S. Capitol Rotunda, making Lavinia Ream famous. She was 23 years old. The next day, Washington’s The Evening Star described the crowds vying to gain entrance to the Capitol for a first glimpse of her statue. “The vast assemblage filling the rotunda was made up of every class—the most distinguished, and the lowliest of the nation—and among the most interested spectators of the scene were groups of colored people, who hold Abraham Lincoln in their heart of hearts.”

Other Work

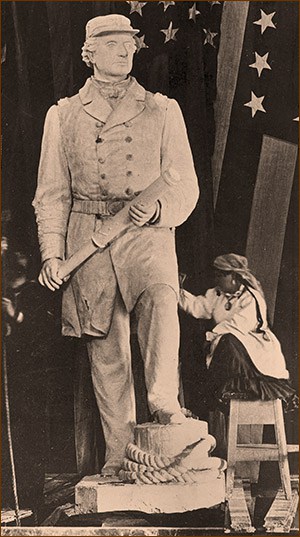

Lavinia Ream’s second government commission was awarded in January of 1875, when she signed a $20,000 contract for the statue of Admiral David (“Damn the Torpedoes! Full speed ahead!”) Farragut that stands in Washington’s Farragut Square. The first major monument to an American naval officer built in the city, it was cast from the bronze propellers of Farragut’s ship, the Hartford.

She would also create sculptures for the National Statuary Hall Collection. More than 40 years later, two bronzes were placed in the Capitol. The first was of Samuel Kirkwood, donated by the state of Iowa. Having always summered in Iowa, Ream was commissioned in 1906 to create a statue of Kirkwood, then governor and U.S. Senator from that state.

She also designed the first statue of a Native American, Sequoyah. Commissioned in 1912, it memorialized the Native American recognized for inventing a written alphabet for the Cherokee language. But Ream died before Sequoyah was completed, leaving its completion to sculptor George Zolnay. It was donated in 1917 to the National Statuary Hall Collection by the state of Oklahoma, where its town of Vinita is named for Lavinia Ream.

Marriage and the Gap Years

In 1878, before she finished Farragut, she married Richard Hoxie, a lieutenant in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in a ceremony attended by most of the U.S. Senate. In the face of of Hoxie’s objections, Ream gave up her career as an artist, focusing instead on being a wife and mother as she accompanied him on his military postings until he retired from the Army in 1908.

After all, respectable middle-class women of her time weren’t expected to pursue careers — even an unconventional and talented figure like Lavinia Ream. Then again, women had to be unconventional if they aspired to great things in a time of even greater obstacles.

Death

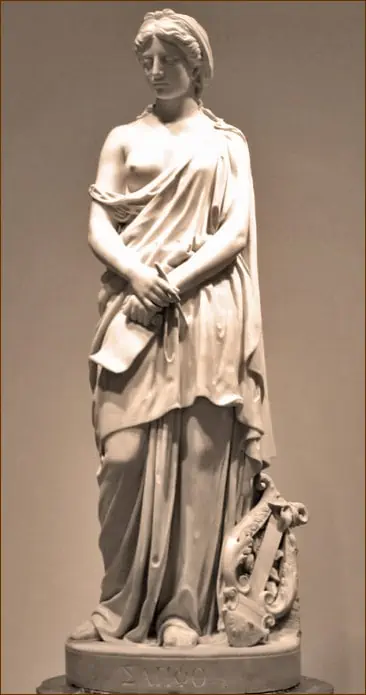

Lavinia Ellen “Vinnie” Ream Hoxie died in Washington, DC, in 1914 following kidney disease and uremic poisoning. She was buried in Arlington Cemetery, her grave marked by a replica of her sculpture Sappho.

An iconic figure for the National League of Pen Women, Ream is notable for her contributions to the letters, art and music. In 2015, the NLAPW created the Vinnie Ream Award, honoring winners in the categories of art, letters, music and multi-discipline at the biennial Vinnie Ream Banquet held in Washington, DC.

Called “the most prominent American woman sculptor of the 19th century,” Lavinia Ream left us the legacy of a sculpture by someone who had spent a significant amount of time with Lincoln near the end of his life, then seen him pass into public memory. As she put it, “so lately had I seen and known President Lincoln, that I was still under the spell of his kind eyes and genial presence when the terrible blow of his assassination came and shook the civilized world.”

I want to thank you so much for this blog! I highly commend your skills for going deep beyond the “usual suspects” and finding the less celebrated but equally important trailblazing women!