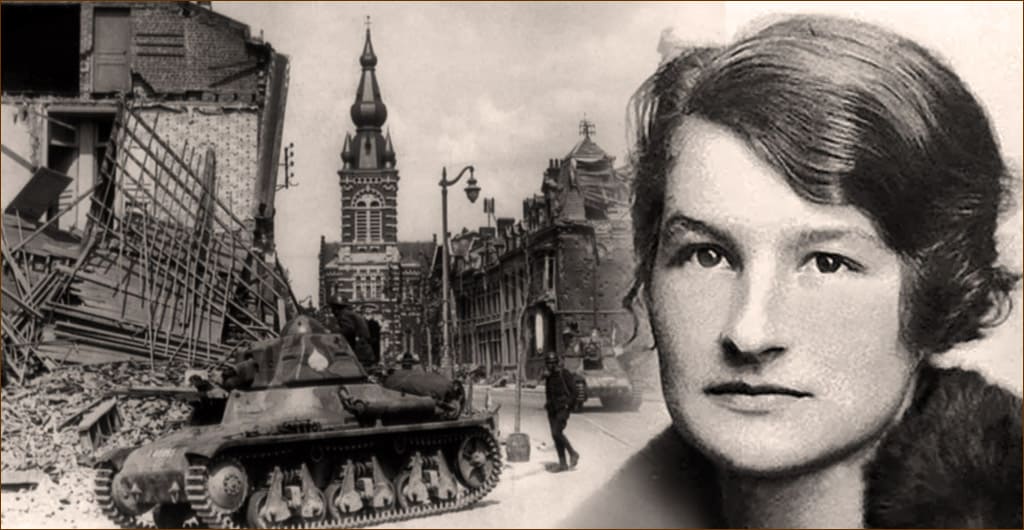

Virginia Hall never spoke publicly about her remarkable life because she knew too many people who “were killed for talking too much.” So, until recently, her story was known only within the intelligence community, where documents were known to disappear and code names were so numerous it was hard to know who was who.

Banker’s daughter

Hall was born into wealth as a Baltimore banker’s daughter in 1906, raised to marry within her privileged class and quietly conform to society’s gender norms of the time, when women were by and large considered of no importance. Instead, she wound up with a wooden leg, being chased through Europe by Nazis as “the most dangerous of all Allied spies” in World War II.

After brief stints at Radcliffe and Barnard colleges, where she studied French, Italian and German, Hall went to Europe to continue her education. It was there she set her sights on becoming an ambassador with the Foreign Service. But every application she submitted was turned down because of the State Department’s bias against women; at the time, only six of its 1,500 staffers were female.

Amputated leg

She took a clerical job at the U.S. embassy in Warsaw, Poland, in 1931 before being assigned to the consulate in Turkey. It was there, at age 27, while hunting little birds called snipe, she shot herself in the left foot. Gangrene set in, causing her left leg to be amputated below the knee. Fitted with a prosthesis, Hall’s recovery was long and difficult. The painted wooden leg with its aluminum foot weighed eight pounds, and was held in place by leather straps on a corset around her waist. Despite everything, she soon realized she had been given a second chance at life. And she didn’t intend to waste it sitting behind a desk.

With the outbreak of World War II, as Germany invaded France in 1940, Hall went to Paris as a volunteer to drive ambulances for the French army. But once France capitulated, she went to England, where an undercover agent put her in touch with British intelligence. Which is how a one-legged American woman volunteered to become one of the first British Special Operations Executive agents sent into Nazi-occupied France in 1941.

Convents and brothels

Virginia Hall was a natural when it came to espionage. Staying at a French convent, she persuaded the nuns to help her. Befriending a female brothel owner, she received information French prostitutes gathered from German troops. She organized French Resistance fighters and provided them with intelligence and safe houses. And, on more than one occasion, she masterminded jailbreaks of captured fellow agents. Eventually, the Germans realized the person who always seemed one step ahead of them was a woman of unknown nationality they called “the limping lady.”

Hall also proved to be a master of disguise. Changing her appearance, she became four different women in a single day, operating under four different code names, constantly on the run from the Nazis — specifically, the infamous Klaus Barbie, known as the “Butcher of Lyon” for personally torturing French prisoners of the Gestapo.

‘Most dangerous spy’

Outraged by being outsmarted by a woman — and a one-legged woman at that — Barbie posted “wanted” posters of Hall as “The Enemy’s Most Dangerous Spy — We Must Find and Destroy Her!” At the end of 1942, he almost succeeded. But Hall narrowly escaped to Spain, walking three days for 50 miles in heavy snow over the Pyrenees Mountains on her often-clunky wooden leg. During the trek, she sent a communiqué to Special Ops Headquarters saying she was fine, but Cuthbert was giving her trouble. They replied, “If Cuthbert is giving you difficulty, have him eliminated.” Little did they know Cuthbert was the code name she had given her prosthesis.

In 1943, Virginia Hall returned to England, where she was quietly honored for her wartime service and made an honorary Member of the Order of the British Empire. Her Special Operations Executive commanders cited her bravery and success in the field as changing their minds about the role of women in combat.

U.S. OSS

Eventually, the adventure bug bit Hall again and she asked to go back to France. The British refused, fearing it was still too dangerous for her. But as luck would have it, America’s intelligence service, the Office of Strategic Services, was just getting off the ground — and they had absolutely no presence in France. So in 1944 the OSS forged a French identity for one Marcelle Montagne (codenamed Diane) and assigned Hall to central France. But with the Gestapo still looking for the mysterious limping lady, she knew it would be more difficult than ever to operate undercover.

Virginia Hall, who had described herself as “capricious and cantankerous;” who once went to school wearing a bracelet of live snakes wrapped around her arm; and who had already outsmarted Klaus Barbie on one good leg was up for the challenge. She found a makeup artist who taught her to draw wrinkles on her face, and even visited a London dentist who ground down her beautiful white teeth so she would look more like a French milkmaid.

French Resistance

Her second undercover tour in France was even more successful than her first. Working with a network of 1,500 people (one of whom, a French-American soldier named Paul Goillot, would later become her husband), Hall mapped out and called in airdrops for the French Resistance fighters who blew up bridges, attacked Nazi convoys, sabotaged trains and reclaimed whole villages before the Allied troops advanced deep into France.

Both the British and the French recognized Hall for her service — but in private ceremonies. When President Harry Truman wanted to honor her with a public White House ceremony, she declined, saying she was “still operational,” and preferred to remain undercover. So, in 1945, General William Donovan, then head of the OSS, presented her with the Distinguished Service Cross in a private ceremony — the only one awarded to a civilian woman for service in World War II.

After the war, Hall remained in the intelligence community. She was initially sent to Venice, mainly because she was fluent in Italian, to focus on economic, financial and political intelligence — especially on the Communist movement and its leaders –then worked for a CIA front organization associated with Radio Free Europe.

Post-war CIA career

In December of 1951 she officially started her CIA career. For 15 years, she used her covert-action experience in support of resistance groups in Iron Curtain countries. Yet, once again, she found her career stymied by sexism, just as it had been when she was repeatedly turned down by the State Department in her twenties, as male colleagues referred to her as “that gung-ho lady left over from the old OSS days overseas.”

Virginia Hall reached the CIA’s mandatory retirement age of 60 in 1966, returning to civilian life to live with her husband on a Maryland farm. She died in 1982 at age 76, and was buried in Druid Ridge Cemetery in Pikesville, MD, her story and wartime exploits still veiled in the secrecy of the intelligence community she served so well.

Four books and two movies

But today that veil has been lifted. A display is dedicated to her at the CIA’s top-secret museum. Four books about her remarkable life have been published, with two movies in the offing. And new recruits at today’s CIA report for training to a building named The Virginia Hall Expeditionary Center.

In the Spring of 2018, three dozen people, including Virginia Hall’s niece and great-niece, gathered on a stretch of York Road in Baltimore County to dedicate a historical marker honoring the Baltimore native and super-spy. That same year, Gina Haspell assumed the mantle of the CIA’s first female director and spoke of standing “on the shoulders of heroines who never sought public acclaim” as they served the agency and its predecessor, the OSS, challenging gender roles and breaking down barriers. Naturally, she didn’t name names; but we know for certain that one of those heroines was Virginia Hall.

Just finished the book, “A Woman of No Importance” The untold Story of the American Spy Who Helped Win World War II.” Ms. Hall’s contribution to clandestine operations and personal drive is an inspiration to those who respect and understand the price of freedom throughout the world. Her story must serve as a lesson to all young women and men who protect and defend our country.

Just watched the movie A Call to Spy on Netflix. History needs to be shared so we can learn of such bravery, and yes, by women. I googled to find this site. I am filled with renewed patriotism. Thank you!

Thank God for sending the right people at the right time. How lucky we all are because of her. I am in amazement of this women’s bravery courage and supreme intelligence. This type of person only comes around once in a lifetime.