Frances Perkins (1880-1965) was a pioneering feminist and America’s first female cabinet member, serving as President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Secretary of Labor from 1933 to 1945. A dedicated civil servant, and an equal in a field dominated by men, her vision improved the lot of every working man and woman in America.

Boston-born Frances Perkins earned degrees in chemistry, physics, economics and sociology from Mount Holyoke, the Wharton School, the New York School of Philanthropy and Columbia University respectively.

Self-made woman

A self-made woman with strong Yankee values, she made her bones working to find jobs and safe lodging for female workers as part of the Philadelphia Research and Protective Association; investigating malnutrition in Hell’s Kitchen; and serving as executive secretary of the New York City Consumer’s League, where she focused on factory sanitation and safety, along with legislation to limit work hours for women and children.

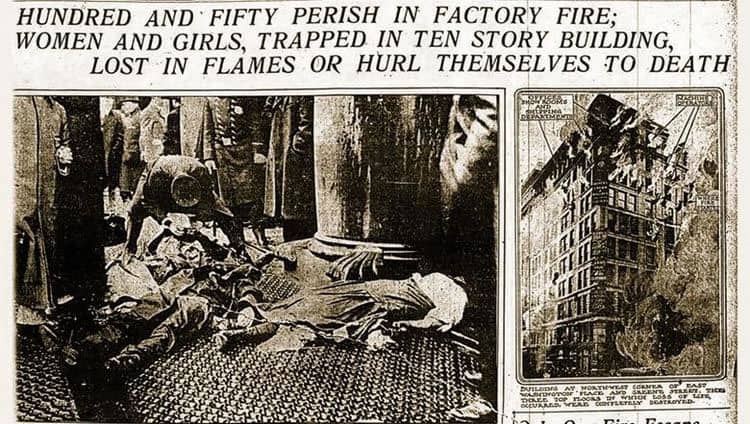

But her life changed on March 25, 1911, when she watched in horror as New York City’s Triangle Shirtwaist Factory went up in flames. One hundred forty-six workers were killed; most were young women, including 47 who jumped from the building’s eighth and ninth floors to avoid the flames. She later recalled that day as “the day the New Deal was born.”

An early and avid feminist, Perkins spoke to a New York audience in 1913 about the importance of women being equal to men in every sphere of life in what the New York Times described as “the first feminist mass meeting ever held.”

Suffragette campaigner

Her career in government took root when she campaigned with the suffragettes for four-time New York governor Al Smith, who appointed Perkins to his Industrial Commission in 1919. When, ten years later, Franklin D. Roosevelt succeeded Smith as governor, he chose her as the first Commissioner of New York State’s Dept. of Labor.

Secretary of Labor

But before Perkins agreed to serve, she presented Roosevelt with a list of policies and priorities she intended to pursue. They included a 40-hour work week; minimum wage; unemployment insurance; worker’s compensation; the abolition of child labor; federal aid to the states for unemployment benefits; Social Security; and universal health insurance. She made it clear she would only serve if Roosevelt agreed with her goals. FDR endorsed every item on her list, and Perkins took her seat as his Secretary of Labor.

Secretary Perkins did exactly what she set out to do. Her accomplishments during her tenure were nothing short of amazing. Child labor was outlawed. Minimum-wage and maximum-hour laws were enacted. The work week for women was cut to 48 hours. And, through the National Labor Relations Act, workers won the right to organize and engage in collective bargaining.

Roosevelt’s Committee on Economic Security, chaired by Perkins, also recommended nationalizing unemployment and retirement insurance, with provisions for old-age pensions, unemployment benefits, workers’ compensation and aid to the needy and disabled. It was Secretary Perkins’ relentless pursuit of this ideal that resulted in the Social Security Act being signed into law in 1935.

‘Perkins New Deal’

Perkins resigned in 1945 after Roosevelt’s death, having been the longest-serving secretary of labor, and only one of two cabinet members to serve the full length of the Roosevelt presidency. A 1944 article in Collier’s magazine summed up her body of work over 12 years as “not so much the Roosevelt New Deal as the Perkins New Deal.”

Perkins left Washington in 1945, only to return two years later when President Harry Truman asked her to serve on the U.S. Civil Service Commission — a position she held until 1953.

Frances Perkins never slowed down, continuing to teach, write and lecture publicly until her death in 1965, at age 85, at New York City’s Midtown Hospital. At the age of 80, she spoke to a packed audience of Social Security Administration employees on “The Roots of Social Security,” and lectured at Cornell University just two weeks before suffering a fatal stroke.

Fifteen years later, in 1980, President Jimmy Carter renamed the United States Department of Labor building in honor of the woman who once said, “I came to Washington to work for God, FDR, and the millions of forgotten, plain, common workingmen.” She is buried in Newcastle, Maine, beneath a simple stone with her name and the inscription, “Secretary of Labor of U.S.A. 1933-1945.”