Were it not for this Wednesday’s Woman, baggers at supermarkets all over America would not be able to ask that all-important question: “Paper or plastic?” Margaret Ellen Knight is the inventor of the flat-bottomed paper bag that is a staple of American shopping life.

She was a tinkerer for as long as she could remember. Born in Maine in 1838 and raised by a widowed mother, she was a tomboy who knew her way around tools. She loved to make toys for her brothers; and her kites and sleds became the envy of all the neighborhood kids.

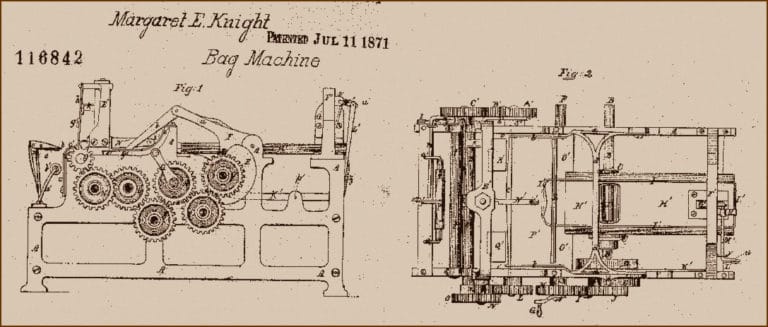

After her father’s death, the family moved to New Hampshire, where Margaret and her siblings became part of the child labor force that powered New England’s fabled textile mills.

Steel-tipped shuttles

There, at age 12, she saw one of the steel-tipped shuttles fly off a power loom at high speed, causing grievous injury to another worker, and got the idea for her first invention — a shuttle restraint that kept shuttles from flying off the loom whenever a thread broke. The mill owner installed her auto-stop guards on all his looms, and Knight was still in her teens when her invention swept the cotton industry. Despite her ingenuity, the idea of patenting the idea never entered her mind.

Knight left the textile mill in her late teens, cycling through a series of jobs to help support her family.

Paper bag company

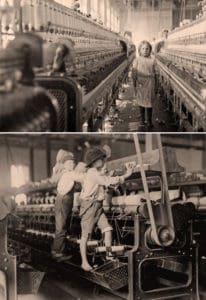

After the Civil War she found work in Massachusetts at the Columbia Paper Bag Company, making bags by hand for $1.50 to $3.50 a week, working 10 hour days. But the bags were envelope-style, with the bottoms glued together in a V-shape, and gusseted sides that expanded, but still limited how much each bag could hold.

That got Knight thinking how much more useful paper bags would be if the bottoms were flat. But square, flat-bottomed bags would have been incredibly labor-intensive and expensive, requiring workers to fold and glue the seams that go into a flat-bottomed bag (known in the paper industry as a satchel-bottom bag). Naturally, Knight’s inventor brain kicked into high gear with an idea for a machine that could cut, fold and glue all those seams together with the turn of a crank to produce paper bags that would be the forerunners of the flat-bottomed bags found everywhere today, from McDonald’s drive-thru window to your local market.

These were the days when society didn’t think women were capable of inventing something practical, something that was of real value. This is where a machinist named Charles Annan enters the story of Margaret Knight and her bag machine.

Patent prototype

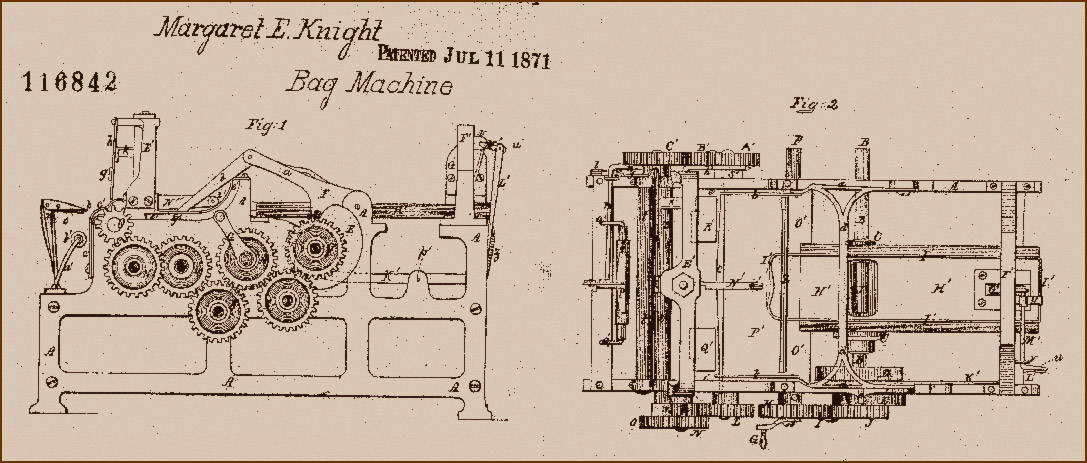

Unlike the auto-stop device she had invented as a teenager, Knight was determined to patent her latest invention. She soon learned the patent office required an iron prototype of her machine, which she couldn’t make on her own. So she brought her wooden design to a machine shop for fabrication.

Annan stopped by often — a little too often — to examine the work with the thought of stealing Knight’s idea and rushing it to the patent office as his own, which he did. When Knight eventually filed for her patent, she was taken aback when her application was rejected on the grounds that a patent for the same machine had already been awarded to one Charles Annan.

A rare court case

Margaret Knight took Annan to court in 1868 to fight for the patent that was rightfully hers. No small thing for a single woman in the 19th century, considering she was paying $100/day for a Washington patent attorney. Annan’s argument? No woman could ever design such an innovative machine. It was utterly impossible.

Knight simply wasn’t having it. She produced witnesses from New Hampshire and Massachusetts to attest to her machine skills. The bag factory boss bolstered her claim, testifying that the idea for a machine to make flat-bottomed bags came out of a conversation between him and Knight and, further, that he had no doubt whatsoever it was her idea. The mechanic who fabricated the patent prototype swore he made it from Knight’s original wooden design. And Eliza McFarland, with whom Knight would live for over 40 years, recalled watching her make one drawing after another of her machine, always tweaking and improving on the same design. Finally, Knight produced all manner of papers and models documenting her design process, including entries from personal diaries which she refused to read aloud.

Court victory

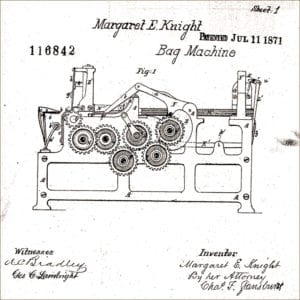

It worked. Margaret Knight won her court case and in 1869 filed the necessary paperwork with the U.S. Patent Office. Two years later, on July 11, 1871, she received patent #116842 for her bag machine. Her invention revolutionized the paper industry, with square-bottomed paper bags quickly replacing the net bags or cumbersome boxes people had used for years.

100 different inventions

Throughout her life, Knight was awarded more than 20 patents for almost 100 different inventions. She created a machine cobblers used to cut the soles of shoes; a sewing machine reel; a pronged barbecue spit for cooking meat; a paper-feeding machine; a numbering mechanism; a dress and skirt protector; a clasp to keep robes modestly closed; and even devices for rotary engines when she developed an interest in automobiles late in her life. At age 70, she was still working 20 hours a day on new inventions.

At the time of her death in 1914, an obituary described the 76-year-old Margaret Knight as a “woman Edison.” Yet she died leaving an estate valued at only $275.05, the equivalent of about $7,000 today.

Hall of Fame inductee

Knight was inducted into the Paper Industry International Hall of Fame in 2006. At that time, more than 7,000 machines throughout the world were producing Knight’s flat-bottom bags, with major suppliers located in the US, Germany, France and Japan. Her machines produce 200 to 650 paper bags a minute that can be found in supermarkets, department stores and bakeries; in lunchrooms and at home, where we use them for composting and recycling yard waste.