Fans of the popular PBS show “Call the Midwife” tune in every Sunday night to follow the lives of Trixie, Val, Nurse Crane and Lucille, bicycling through the cobbled streets of London’s East End, as they bring new life into that region’s poorest community. But closer to home, very few people know the name of the woman who brought nurse-midwifery to the United States and, in the process, changed America’s rural health care delivery system forever.

Swiss finishing school

Mary Breckinridge was born into southern aristocracy. Her grandfather was James Buchanan’s vice-president, and served in Jefferson Davis’ Confederate States of America’s cabinet. Her father was Grover Cleveland’s ambassador to Russia’s Czar Nicholas II in the late 1890s. She was educated by private tutors and went to a Swiss finishing school before coming home to complete her education at Connecticut’s Low and Heywood School, whose curriculum focused on literature, science and culture.

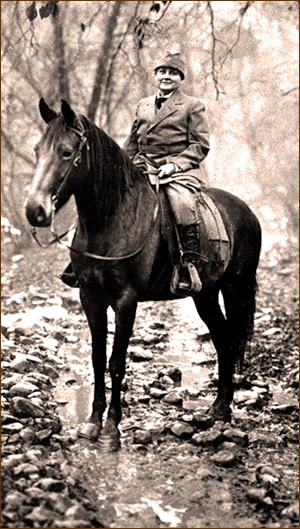

Little did she know she’d find her life’s calling astride a horse, navigating tricky mountain trails through shallow streams, bringing new lives into the poorest reaches of southeastern Appalachian Kentucky.

Both children died

Breckinridge married in 1904. When her husband died suddenly just two years later, she decided to go into nursing. She entered St. Luke’s Hospital Training School for Nurses in New York, graduating in 1910. After remarrying in 1912, she retired from nursing to raise a family. Within two years, she gave birth to a son, Breckie, followed by a daughter, Polly, born prematurely in 1916. But tragedy struck when her daughter died within several hours of her birth, followed by her son’s death in 1918. It was after his death Breckinridge left her husband to return to nursing, volunteering with the American Red Cross in World War I.

In Europe, she was assigned to the American Committee for Devastated France, where she remained for three years. During that time, she organized disaster relief, a special program for children and expectant mothers, and a Child-Hygiene and Visiting Nurse Association for which she was awarded the Medaille Reconnaissance Français. It was also the first time she was exposed to British nurse-midwives. After visiting London, she realized nurse-midwifery would be a perfect fit for rural America’s expectant mothers and young children.

After the war, she came home to take postgraduate courses in public health at the Teachers College of Columbia University. Her plan was to focus on health problems in eastern Kentucky, believing that if her ideas worked there, they could work anywhere.

No prenatal care

Traveling on horseback, she surveyed families about their needs and talked with lay-midwives about birth practices. She found little to no prenatal care for women who birthed, on average, nine children attended by family members or farmers’ wives who relied mainly on folklore.

With no midwifery training available in the U.S., she returned to England to study at London’s British Hospital for Mothers and Babies, where she was certified as a midwife in 1924. But before coming home, she toured the Scottish Highlands and the wild, remote Hebrides Islands to learn about rural nursing and models of rural health service.

Breckinridge returned to Kentucky in 1925 to begin her life’s work — work that introduced an entirely new type of rural health care system to America, modeled on her experience in Scotland. In May of that year she founded the Kentucky Committee for Mothers and Babies, America’s first organization using nurses trained as midwives under the direction of a single medical doctor. The committee eventually changed its name to the Frontier Nursing Service (FNS).

Saddle bags and hearty horses

In its early days, FNS nurse-midwives navigated Kentucky’s mountain passes and forded swollen streams on horseback, saddlebags packed with the material and equipment they needed. Just as today, children often asked them where babies came from. And, naturally, since babies seemed to arrive after a visit from the nurse-midwife, the children were politely told the nurse-midwives brought them in their saddlebags.

Breckinridge’s Frontier Nursing Service delivered professional health care to the Appalachian region of eastern Kentucky, one of America’s poorest and most isolated regions. Its model of rural health care delivery included a decentralized system of nurse-midwives, district nursing centers, and a hospital serving a 700-square-mile area.

Through her influential family connections and a series of speaking engagements, Breckinridge raised over $6 million to support her organization. She initially relied on British-trained nurse-midwives to provide prenatal and childbirth care in clients’ homes, where they served as both midwives and family nurses. Their motto was that if the expectant father could come to the nurse, the nurse would get to the mother. Babies were delivered day and night, no matter the weather. And no one was ever turned away. FNS charged a minimum of $2 for general nursing care and $50 for births, payable in money, eggs, guns, fresh vegetables, or whatever the family could provide.

First school of midwifery

An FNS-trained midwife started America’s first school of midwifery in New York in 1932. Seven years later, when many of its staff wished to return home with the outbreak of World War II, it was no longer possible to send American nurses to England to train. So, that same year, Frontier Graduate School of Midwifery enrolled its first class. It continues to operate today in Hyden, Kentucky, as Frontier Nursing University.

In its first 50 years, Mary Breckinridge’s Frontier Nursing Service delivered 17,053 babies with only 11 maternal deaths. And today, if you drive along State Highway 80 to Riverfront Park near the Mary Breckinridge ARH Hospital, you’ll be met with a life-sized bronze statue of her, dedicated in 2010, on horseback as she leans down to touch the hand of a child reaching up to her.

Mary Breckinridge ran the Frontier Nursing Service for 37 years until her death at age 84 in 1965, after battling leukemia and suffering a stroke. Friends blanketed her casket with ivy and mountain laurel intertwined with roses gathered from the garden of Wendover, her original log cabin and one-time headquarters of the Frontier Nursing Service. Recognized as the first to bring nurse-midwifery to the United States, she is buried in Lexington Cemetery.