Whoever coined the phrase “more than just a pretty face” could have been describing this Wednesday’s Woman. Hedy Lamarr, the exquisite Hollywood beauty of the 1930s and ’40s, was born into an Austrian Jewish family as Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler in 1914. She would ultimately go on to become the Hollywood star we all know, as well as a highly successful engineering innovator who most of us were never aware of.

At 18 the young Hedwig married her first husband — an arms manufacturer for Austria’s fascist government who, according to Lamarr’s autobiography, hobnobbed with Mussolini and Hitler and demanded complete control over her. The story of how she left him is, in itself, the stuff of Hollywood. Lamarr reportedly hired a look-alike maid, dosed her with sleeping pills, stole her uniform and fled the house on a bicycle.

Name change and stardom

She met Hollywood mogul Louis B. Mayer in Paris. When he suggested she change her name and come to America, Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler chose La Marr to honor silent film star Barbara La Marr — ironically known as “the girl who was too beautiful.” Arriving in the United States in 1938, she took the silver screen by storm, starring opposite some of Hollywood’s most famous leading men like Charles Boyer, Clark Gable and Spencer Tracey.

While she put her considerable physical assets to good use, starring in 30 films from 1938-1958, there was more to Hedy Lamarr than met the eye. She was a tinkerer; someone who saw problems and came up with solutions; she was an inventor. After she showed record-setting pilot and aviation magnate Howard Hughes a sketch of an airplane wing designed to increase the aircraft’s speed, he dubbed her a genius and gave her a drafting table and access to scientists to help develop her ideas.

Lamarr’s inventions included a pivoting chair that attached to the shower wall so people could sit, shower, and simply pivot out to towel off; a better Kleenex box; improved traffic light; and a tablet that, when dropped into a glass of water, transformed it into a fizzy drink.

“Frequency hopping”

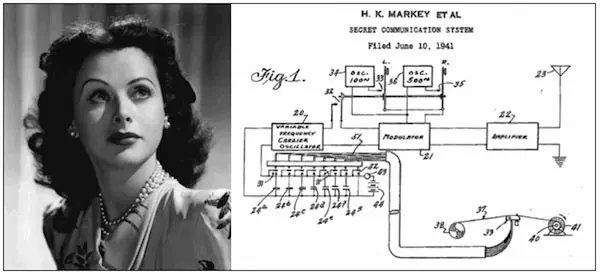

But in 1942, the war in Europe was on Lamarr’s mind. It was the year Roosevelt and Churchill agreed to make Germany’s defeat their first priority as Germany held talks to develop its “Final Solution” for its Jewish population. Lamarr remembered the countless hours spent during her first marriage, listening to her husband talk state-of-the-art weaponry with munitions dealers. Collaborating with New Jersey-born composer (and former U.S. munitions inspector) George Antheil, Lamarr invented a remote-controlled, secret communications system designed to thwart the Nazis. It featured something called “frequency hopping.” Manipulating radio frequencies at random intervals between transmission and reception produced an unbreakable code that could block classified messages from being intercepted by Germany and result in more successful Allied torpedo attacks. They were awarded U.S. Patent 2292387 for their Secret Communication System in August of 1942. Lamarr and Antheil, believing it their patriotic duty, signed the patent over to the U.S. Navy.

But the Navy, skeptical of its practicality, basically told Lamarr not to give up her day job — she was advised to use her star power to raise money for the war effort. In response, she raised a record-breaking $7 million worth of war bonds in one night alone.

The root of wireless technology

U.S. Patent 2292387, never implemented, gathered dust and expired in 1959 — the same year as George Antheil. But when the Navy detected subs during the 1962 Cuban missile crisis and its Cuban blockade, it started working with Lamarr’s system to develop the electronics for spread-spectrum technology that is the basis of the wireless technology in today’s cell phones, fax machines, Wi-Fi and GPS.

In 1997 Lamarr’s work was honored with the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s Pioneer Award. Later that same year Hedy Lamarr, at age 82, became the first female recipient of the BULBIE Gnass Spirit of Achievement Award, a coveted lifetime accomplishment for inventors dubbed “the Oscar” of inventing.

Inventors Hall of Fame

Once lauded as “the most beautiful face in the world,” fate was not kind to Hedy Lamarr. She had six marriages and divorces. Studio heads eventually stopped calling. Good movie roles dried up and her money ran out. A series of nips and tucks over the years in an effort to preserve her looks had unfortunate results. Hedy Lamarr passed away in seclusion in a one-bedroom house in Florida in 2000 at 86 years of age. Fourteen years later, she was inducted posthumously into the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

Hedy Lamarr always regretted that people, hearing her name, would just remember a pretty face. The December 2017 issue of the magazine Science put that to rest, shining a light on the “under appreciated intellectual contributions” of a woman who was so much more than just a pretty face.