If there’s one thing the coronavirus pandemic has taught us, it’s that unsung heroes are all around us — people doing great things or committing acts of bravery or self-sacrifice quietly, without celebration or recognition, sacrificing their time and energy for the good of others. So it’s understandable that neither a small community in Ithaca, NY, nor people working at Cornell University knew they had been, for years, in the presence of a true, unsung, World War II hometown hero, Florence Finch.

Loring May Ebersole (later known as Florence Finch) was born in 1915 to a Filipino mother and American father who fought in the Philippines during the Spanish-American War and decided to settle there. Little is known about her early life until she graduated from high school and found a job as a civilian stenographer at the U.S. Army Intelligence Headquarters in Manila. It was there she met the man who would become her first husband, Charles Smith.

Husband killed in action

After the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, Smith reported to his PT boat for duty, only to be killed in action in 1942 when his boat was hit while resupplying American and Filipino troops trapped on Corregidor Island and the Bataan Peninsula. He and Florence had been married for just six months; Manila had fallen to the Japanese five weeks earlier.

Being half Filipino, the young widow was able to hide her American connections when she took a job with the Philippine Liquid Fuel Distributing Union, then under Japanese control, writing vouchers for gasoline, diesel fuel, oil and alcohol distribution. Little did her employers know Smith was working closely with the Philippine Underground, diverting fuel supplies to the resistance while helping arrange for the destruction of stocks of critical items earmarked for shipment to Japanese occupation forces. Carefully falsifying records, she managed to divert as much as 250 gallons of fuel a week — a valuable black-market commodity that helped get medicine and food to hundreds of American POWs.

Supplying POWs

Ironically, it was during this time she learned her former boss, Lt. Col. E. C. Engelhart, had been taken prisoner, and how badly he and his fellow POWs were being treated. Networking with other former employees of Engelhart along with Manila’s private citizens, she did what she could — putting money aside from her salary to buy scraps of meat and fish, smuggling food and medications in to them and taking their laundry out so they at least had clean clothes, until the Japanese discovered her activities and arrested her in October of 1944.

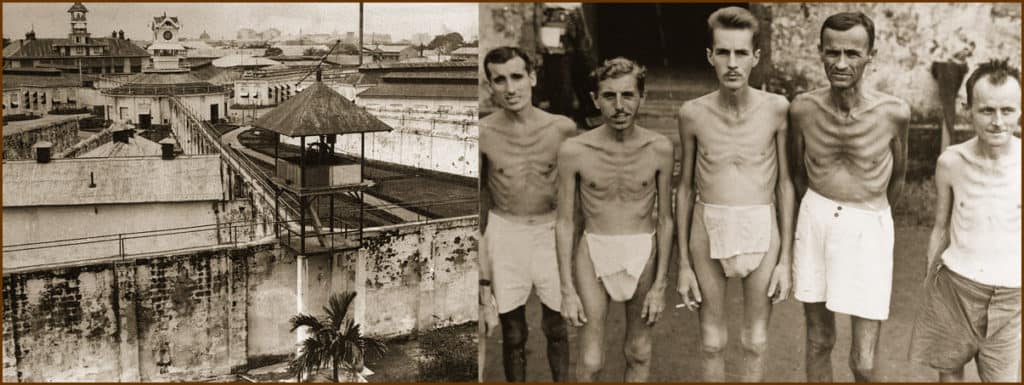

Smith was imprisoned and tortured regarding her activities with the resistance before being sent to Bilibid Prison. Considered a high-value POW, she was placed in solitary confinement in a cell measuring 2′ X 4′; with no room to stand, she could only squat. Dressed in GI-issue pajamas and given one bowl of rice gruel a day, she heard the suffering of other POWs, soon realizing the names being periodically called were those of her fellow captives facing execution.

Tortured by Japanese captors

Her captors brought her out and strapped her to a chair; metal clamps were placed around her fingers through which an electric current passed while she was repeatedly interrogated. Throughout her torture, she never betrayed the resistance or named those with whom she had worked. Unable to break Smith, the Japanese finally conducted a sham trial before sentencing her to three years of hard labor in Mandaluyong, just outside Manila, where the Women’s Correctional Institution was housed.

Florence Smith was held captive until February of 1945 when, weighing just 80 pounds, she was liberated by American forces following the Battle of Manila. Soon after, she left the Philippines for Buffalo, New York, to live with relatives. Not long after her arrival, she enlisted in the U.S. Coast Guard Women’s Reserve to, in her words, “avenge the death of my husband.”

U.S. Coast Guard Women’s Reserve

The women in the Coast Guard reserve corps were known as SPARs. And more than 10,000 women volunteered for service in the little-known organization between 1942 and 1946 under the command of Capt. Dorothy C. Stratton, who came up with the name. After giving it considerable thought, the acronym came to her for two reasons. First, SPAR was the acronym for the U.S.C.G. motto, “Semper Paratus – Always Ready.” And the nautical meaning of spar is a ship’s supporting beam, which is how Stratton saw her organization — as an important support. Her reservists took over men’s stateside military jobs, freeing them up for overseas combat duty. After World War II, the SPARs were demobilized.

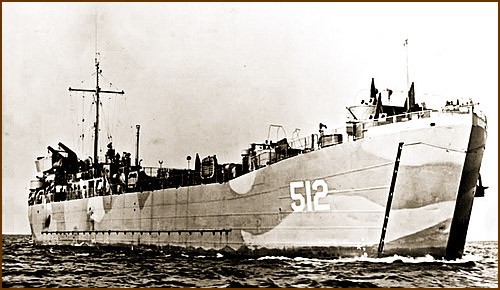

Florence Smith was one of the first Asian-American woman to wear a Coast Guard uniform. She enlisted in July 1945 aboard the USS Burnett County (LST-512), then tied up in Buffalo Harbor. A year earlier, the landing ship had been assigned to the European Theater, participating in the Normandy Invasion in June, 1944. But when a storm in the English Channel capsized her, “breaking her back,” the Burnett County was towed to England for repairs before being coming home to America for a war bond tour in the Great Lakes and up the Mississippi, Ohio and Illinois Rivers with stops in Detroit, Rochester, Cleveland, Toledo, Duluth, Milwaukee, Chicago and Buffalo.

U.S. Medal of Freedom

When her U.S.C.G. superiors learned of her resistance work in the Philippines, Smith was awarded the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Ribbon, making her the first woman to be so decorated before being discharged in May, 1946. A year later, she was awarded the Medal of Freedom (today’s Presidential Medal of Freedom) based on testimony given by her former boss, Lt. Col. Engelhart, after he, too, was liberated. Her citation read, in part: “She displayed outstanding courage and marked resourcefulness in providing vitally needed food, medicine and supplies for American Prisoners of War and internees, and in sabotaging Japanese stocks of critical items … constantly [risking] her life in secretly furnishing money and clothing to American Prisoners of War and carrying communications for them.”

Florence Smith later married Army veteran Robert Finch, with whom she settled down and raised a family in Ithaca, New York. Working as a secretary at Cornell University until her retirement, neither her co-workers nor members of her quiet community knew they had a real hometown hero in their midst.

Coast Guard building

But in 1995, the Coast Guard was looking for something special to mark the opening of its new headquarters on the 50th anniversary of the end of World War II. They found it when they discovered Finch. And on March 28, 1995, the U.S. Coast Guard in Honolulu, responsible for 276,000 square miles of Pacific Ocean, named its new $3.5 million headquarters building on Sand Island for Florence Ebersole Smith Finch. Only then was this quiet, modest woman’s story finally told — until then, she had shared it only with her immediate family. She once said, “I feel very humble because my activities in the war effort were trivial compared with those of the people who gave their lives for their country.” Or as her daughter, Betty Murphy, put it, “Women don’t tell war stories like men do.”

Florence Smith Finch died in December of 2016 at the age of 101. The Coast Guard publicly announced she would be given a military funeral with full honors in April of 2017 at Ithaca’s Pleasant Grove Cemetery. The four-month delay between her death and burial speaks to her long history of always putting others first. As she neared the end of her life, she specifically told her family she didn’t want to disrupt their Christmas holidays or make mourners travel through what she knew could be a punishing Ithaca winter.

By the time she passed, it seemed everyone but her family had forgotten about Florence Finch’s bravery and acts of heroism during World War II. Were it not for the Coast Guard’s public announcement of their graveside memorial to her, the story of this humble, unsung hometown hero would never have been picked up by nationwide news media.

But the United States Coast Guard never forgot. Three years later, in 2019, the U.S.C.G. announced its intention to name one of their newly-ordered Fast Response Cutters, scheduled for delivery beginning in late 2023, for “Seaman First Class Florence Finch.” Her life also became the subject of a book by Robert J. Mrazek titled The Indomitable Florence Finch, published in 2020, in which the author used the diary of Lt. Col Engelhart, as well as Finch’s correspondence to him, to tell her amazing story.

Florence Finch was an amazing woman! A true hero, selfless, generous, and brave. Thankyou for another wonderful article.