Had computers and Spell Check! existed in 1910, we might never know the name Ida Holdgreve. Lucky for her, a simple typo in a local newspaper ad led to her finding a place in history as the first woman to work in the American aviation industry.

In 1910, Orville and Wilbur Wright needed a seamstress to work in their new factory in West Dayton, Ohio, and placed an ad: “plain sewing wanted.” At least that’s what ran in the paper. What they actually wanted was someone to do “plane” sewing. But in the early years of the 20th century, when flying machines made of wood and fabric seemed as out of place as the term “plane sewing,” a typesetter took the liberty of changing the spelling and the rest, as they say, is history.

First airplane factory

Locals watched as two unusual buildings rose in the dry cornfields not far from the brothers’ West Dayton home in 1910. Images from Wright State University Libraries’ Special Collections show their parapets rising from the front and back of long, light-filled structures with arched, skylit midsections. They would become the Wright Company factory — America’s first airplane factory.

Born the sixth of nine children in 1881 in small-town Delphos, Ohio, Ida Holdgreve worked as a dressmaker before moving to Dayton, well on its way to becoming citified in 1908. Two years later, at 29, she saw the help-wanted ad, figured, “I can certainly do that,” and got the job. At a time when society frowned upon single young women working in the city, much less on a factory floor, Timothy Gaffney, author of The Dayton Flight Factory: The Wright Brothers & The Birth of Aviation, believes Holdgreve was the only woman working in the factory.

First aerospace workforce

A photo from Wright State University’s online collection shows her tucked into a corner of the factory where she fed spools of sturdy thread into her sewing machine, transforming bolts of ivory-colored fabric into the skins of wings, rudders and stabilizers — about as far as you could get from the darts, hems and delicate seams of her dressmaking days. The factory employed as many as 80 people, building about 120 planes in 13 different models for both civil and military use. Today, we recognize those employees as America’s first aerospace workforce.

Holdgreve received special training for her new job from Duval LaChapelle, Wilbur Wright’s mechanic in France, who taught her how to cut and sew the cloth, then pull it taut over the airplane’s frame so it wouldn’t rip in the wind. Still, as Holdgreve recalled in a 1975 interview with her hometown newspaper, The Delphos Herald, “when there were accidents, I would have to mend the holes.”

When it came to Orville and Wilbur Wright, Holdgreve remembered them as being very nice despite always being busy. But during a business trip to Boston, Wilbur contracted typhoid fever in 1912 and died within a month, leaving Orville to run the Wright Company alone for the first time. Described as “somewhat lost,” he began missing deadlines, overlooked important business matters, and eventually stopped attending company board meetings.

Three years after his brother’s death, Orville Wright sold the company. But Ida Holdgreve kept her job in the airplane business when Dayton businessman Edward Deeds helped found the Dayton-Wright Airplane Company in 1917 and hired Holdgreve to supervise a department of seamstresses at his main plant in Moraine, Ohio. She recalled working “as a forewoman for girls sewing. The only difference was that instead of the lightweight material I used for the Wright brothers, the material was now heavy canvas, as the new planes were much stronger.”

World War I fighter plane

Dayton-Wright became the largest producer of the DH-4 — the only American-built World War I plane to be flown in combat. Author Tim Gaffney has described Holdgreve as “Rosie the Riveter before there were airplane rivets,” citing her contribution to the war effort.

When the war ended, Holdgreve left wings, rudders and stabilizers behind to take a job sewing draperies in the same Dayton department store from which the Wright brothers had purchased their bolts of muslin fabric for the world’s first plane — the 1903 Wright Flyer. Holdgreve, looking back on her experience in America’s fledgling aviation industry years later, admitted, “At the time, I didn’t realize it would be so special.”

She spent the rest of her life in Dayton and, at 71, stepped away from her sewing machine to care for an ailing sister, her story known only by the local community. Then, in 1969, at 88 years of age, she fulfilled a lifelong dream. Turns out the spry seamstress who had sewed and mended some of America’s first airplanes had never taken to the air herself.

Holdgreve’s first flight: 1969

On a cold November day, wearing spectacles, black gloves, a heavy coat and black Cossack hat, Holdgreve climbed into an Aero Commander piloted by Dayton’s Chamber of Commerce Aviation Council Chairman. Despite not being able to hear very well from her passenger seat, the lifelong seamstress who knew fabrics inside and out described the clouds as looking “just like wool.”

Her story made national news and Ida Holdgreve got her 15 minutes of fame when the Los Angeles Times reported “an 88-year-old seamstress who 60 years ago sewed the cloth that covered the wings of the Wright brothers’ flying machines has finally taken an airplane ride.” Never one to embroider a story, her only response was, “I didn’t think they would make such a big thing out of it. I just wanted to fly.”

Wright Factory Families Project

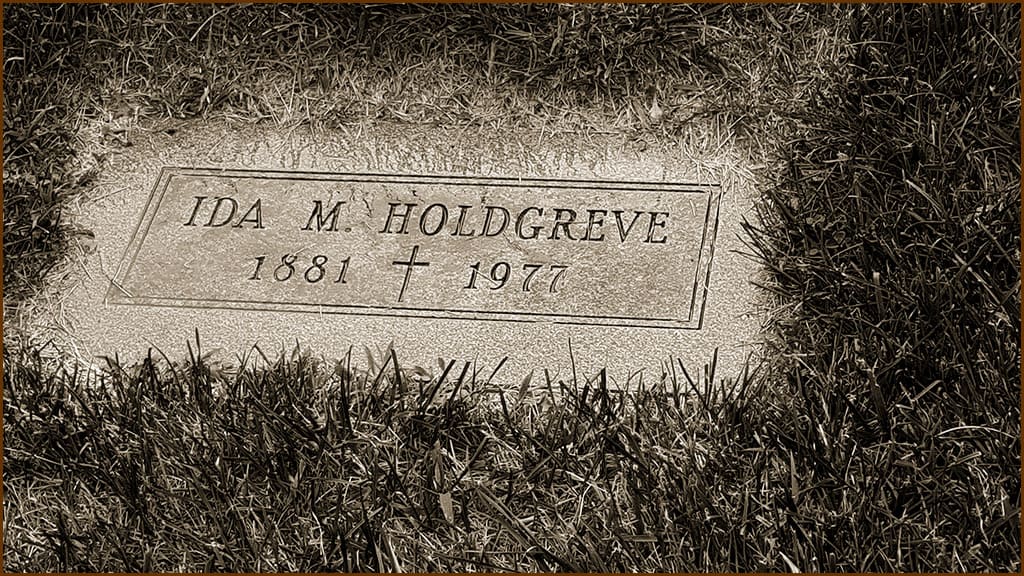

In the fall of 1977, Ida Holdgreve died at the age of 95 and was buried in Dayton’s Calvary Cemetery. Never married, she left no direct descendants. Her story might have died with her had the National Aviation Heritage Alliance and Wright State University Library’s Special Collections and Archives jump-started the Wright Factory Families Project in 2014 — an idea proposed by author Tim Gaffney.

Figuring everyone already knew the story of Wilbur and Orville Wright, he wanted to learn about the Wright Company Factory workers and their stories. After all, they were the people who made the planes that made the careers of the Wright brothers. It didn’t take long for Ted Clark, Holdgreve’s distant cousin, to respond to a query from the Wright Factory Families Project: “While the family always knew about [her] work for the Wright brothers, they never made a big deal about it.”

Original factory building still standing

Today, the original Wright Company factory building still stands, having been repurposed over the century to turn out everything from auto parts to firearms, its true origins seemingly lost to time. Not everyone knew the odd buildings with its arched parapets and bowed spine had once shaped the future of America’s aviation industry, producing the airplanes that kept America in the sky and in World War I.

The Dayton Aviation Heritage National Historical Park, National Aviation Heritage Alliance, and other local organizations hope to change that with their campaign to preserve the famous factory. As a result, in 2019, the twin buildings were placed on the National Register of Historic Places with the hope that one day guests will walk the old Wright Company factory floor where Ida Holdgreve sat at her sewing machine in one corner of the old building doing the “plane sewing” that helped build some of America’s first airplanes.

But her story lives on in other unexpected ways. A piece of fabric and wood from the original 1903 Wright Flyer went to the moon with the crew of Apollo 11 during its first lunar landing mission in July 1969. And portions of original wood and fabric were on board the space shuttle Challenger, tragically destroyed on liftoff; some of the wood and fabric were actually recovered from the shuttle debris, and are now on display at the North Carolina Museum of History.

I learned recently that at the age of 19 my grandmother, Florence McClain (St John), was a seamstress in the factory in 1918. Her father James also applied, but we are unsure if he was employed there. I would love to know any history of this time period. She was an accomplished seamstress and I fondly remember we grandkids (13 of us) received a newly sewn set of flannel PJ’s every Christmas. She began this tradition in 1956 and continued until 1968 when grandpa passed. She never spoke of working in the factory, like Ida she was a selfless servant. She passed in 1983, two years before I earned my “wings” graduating flight school.

Coincidentally, my cousin David St John served in the Air Force as a B-52 pilot for 6 years, as well. I served in the Army National Guard from 1979-2000 serving as a Rotary Wing Pilot in Ohio and Hawaii (1985-1997).