Jessie Tarbox Beals might have spent her life as a teacher, doing “genteel, sheltered, monotonous and moneyless work having neither heights nor depths.” Instead, thanks to a little box camera, a knack for self promotion and pure moxie, she became one of America’s first women to carve out a career in the tough, competitive, male-dominated field of photojournalism.

Tarbox was teaching in Massachusetts when, at age 17, she won a camera worth about $2 selling magazine subscriptions. Intrigued, she soon traded up to a new Kodak camera with its irresistible slogan, “You press the button and we do the rest.” Roaming nearby Smith College campus during summers off, she sold students four portraits for $1 — enough to give her a small income. A few years later, during an adult educational summer camp, she became interested in news photography.

She was still teaching when she married Alfred Tennyson Beals in 1897. Three years later, she ended a 12-year teaching career when her photos of a local fair were picked up by a Vermont paper, making Beals the first published female photojournalist. Not long after, she and Alfred took to the road as itinerant photographers, selling portraits and general photography door to door throughout New England — Beals behind the camera, her husband in the darkroom, processing prints.

When they ran out of money they moved to New York, where Beals was hired in 1902 by the Buffalo Courier — a job that allowed her to freelance for outside news outlets. Within a year, she scored her first exclusive. Outside the courtroom of a sensational murder trial closed to the press, she spotted an open transom window and, in her corset and long skirts, climbed atop a bookcase, lugging a 50-pound, 8 x 10 format camera. Priding herself on her physical strength and agility, she was the only photographer to capture the scene inside the courtroom, her exclusive image printed as front-page national news.

Two years later, Jessie Tarbox Beals was sent to St. Louis for the opening of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition. Set on 1,200 acres and attended by 20 million people over eight months, it showcased the latest in technology, agriculture, arts and culture. Her husband, Albert, would go along to process and print her photographs. There was just one problem: she was denied a press pass. She was, however, given a temporary permit to shoot on the fairgrounds before the official opening.

Permit in hand, she promptly ignored all its limitations, taking photos at every opportunity, even climbing ladders and hoisting herself into a hot air balloon for a birds-eye view of the fairgrounds — a stunt that won her a gold medal from the Exposition for aerial photography. As a result, she became the official photographer at the Exposition for the New York Herald Tribune, Leslie’s Weekly, three Buffalo papers, all the local St. Louis papers and the Fair’s own publicity department.

She became known for her fearlessness and audacity. She even interrupted President Theodore Roosevelt’s tour of the Fair to photograph him, following him throughout the day to get more then 30 shots. Her hustle paid off when she was credentialed as a member of the official party that accompanied him to a reunion of the Rough Riders in San Antonio in March 1905.

In all, she produced over 3,500 photographs and 45,000 prints from the Fair. And while the Louisiana Purchase Exposition brought her recognition, she still struggled to establish herself.

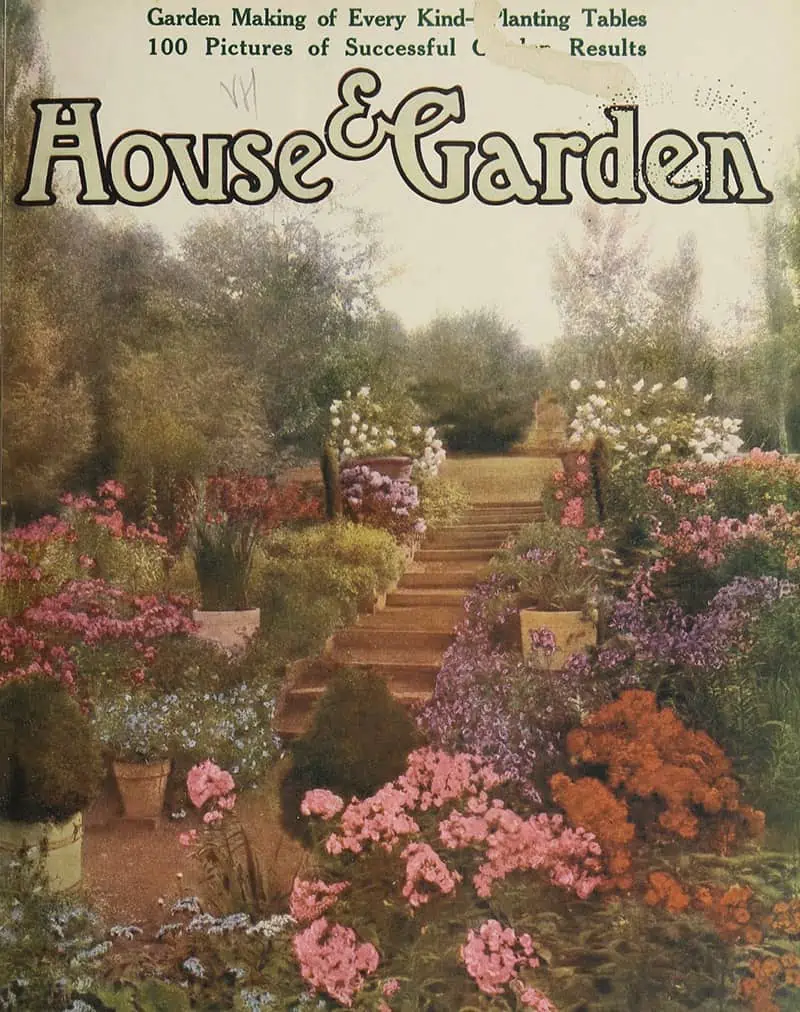

Returning to New York, Beals and her husband opened a small studio when newsrooms wouldn’t hire women as staff photographers. But over the next couple years, her work was published in American Art News and exhibited throughout New York, New England and Canada. She gained broad exposure in publications that included Outing, The Craftsman, American Homes and Gardens, Bit and Spur, Town and Country, Harper’s Bazaar, The Christian Science Monitor, McClure’s Magazine and the New York Times. Their wide-ranging diversity reflected Beals’ willingness to do whatever it took to succeed.

Jessie Tarbox Beals also taught herself to use highly-explosive flash powder that allowed her to do nighttime shoots, giving her the distinction of being one of the first female photographers to use the dangerous stuff. Her flash photography caught the eye of New York’s Charity Organization Society, which used her photos to illustrate the need for reform in New York City’s crowded tenements. Carrying her heavy equipment up and down dark, narrow stairwells and through crowded tenement halls, the flash powder burned bright, illuminating the small, dark spaces to give her photos a sharp, realistic focus.

During her travels as a freelance photographer, Beals met and had an affair with a man who fathered her daughter. She had long wanted a child, and was 40 years old in 1911 when she gave birth to a little girl she named Nanette. Her husband accepted the child as his own and they raised her together. But the marriage grew strained when Nanette required repeated hospitalizations for juvenile rheumatoid arthritis.

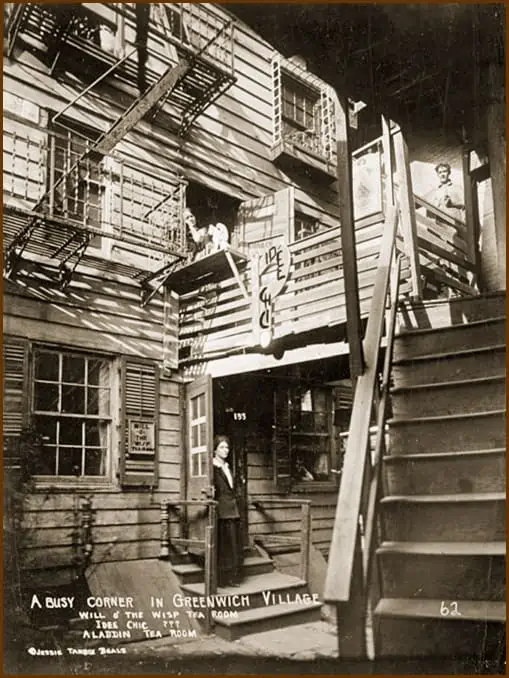

In 1917, Beals left her husband and moved to Greenwich Village with a female friend to open an art gallery, where she displayed her photographs along with others’ artwork, serving tea to friends and customers alike. When she and Albert divorced in 1924, she never remarried.

She spent three years photographing the Village’s Bohemian lifestyle. With business booming after the end of WW I, she took a large loft on Fourth Avenue. Still, like other female photographers of the time, she had to hustle for freelance work when newsrooms wouldn’t hire her. She shot portraits, news photos and street scenes, turning her lens to whatever caught her eye. She later admitted her scattershot approach was not very lucrative, suggesting women photographers specialize if they wanted to make good money.

Beals turned 50 in 1920, just as female photographers were becoming more common. She may actually have done herself in with her talks at clubs and on the radio, freely offering advice to aspiring female photographers. No longer unique in her field, she soon found herself middle-aged and no longer able to hustle for work as she had done for decades.

In the late ’20s, with a daughter to support and her economic prospects in New York bleak, she and Nanette moved to California, where she knew people who lived in artist colonies or worked in Hollywood. Unable to find proper storage, she was forced to sell thousands of her 8 x 10 glass plate negatives to the highest bidders, resulting in the permanent loss of a massive body of her work. But Hollywood was good for Beals — movie stars and the wives of studio executives clamored to have their posh estates and gardens photographed by a renowned New York photographer.

Then came 1929 and the stock market crash. America was plunged into the Great Depression and Beals lost most of her West Coast business, spending the next few years traveling between New York and Chicago with her daughter in search of steady work.

By the mid-1930s, mother and daughter had returned to New York, where Nanette briefly took a job as assistant to another photographer before becoming her mother’s full-time assistant, carrying her cameras and equipment. While Beals’ garden photography saw regular publication and continued to win awards, earning a living from photography during the Depression was tough. But she never gave up. Despite increasing infirmity and illness, she worked up until right before her death, her medical expenses and hospitalizations eating up what little was left of her savings.

In late 1941, Jessie Tarbox Beals became bedridden. A lifetime of hustling to work outdoors and in situations considered too rough and unsuitable for a woman had taken its toll, while a lavish lifestyle had left her nearly destitute. She was admitted to the charity ward of New York City’s Bellevue Hospital, where she died in May of 1942 at the age of 71. Her ex-husband, Afred Tennyson Beals, who still lived nearby, didn’t attend her funeral. She was buried in a narrow strip between the graves of her parents in Williamsburg, Massachusetts, at the Village Hill Cemetery.

Were it not for photographer/anthropologist Alfred Alland, Jessie Tarbox Beals, who shot everything from American presidents and Hollywood’s rich and famous to urban slum children and tenement dwellers, would likely have drifted into obscurity. But with the help of her daughter, Nanette, he was able to find many of her lost negatives, along with her diary and personal papers. And in 1978 he published her biography, titled Jessie Tarbox Beals: First Woman News Photographer.

Today, her photographs and prints can be found in the collections of the Library of Congress, Harvard University, the New York Historical Society and the American Museum of Natural History. The Schlesinger Library at Radcliffe received Beals’ papers and pictures from her daughter in 1982.

Jessie Tarbox Beals was a true pioneer and trailblazer when it came to photography, her eclectic life and wide-ranging body of work encouraging other women to pursue careers behind the lens. Bemoaning her refusal to specialize, she once said, “I opened too many keys to too many doors.” Jessie Tarbox Beals saw that as a failure. What she couldn’t know was that she made it possible for every female photographer who followed in her footsteps to walk through those doors.