Anyone remember riffling through the Sunday papers to get to the comics section? The Sunday funnies, a.k.a. the funny papers, were a family tradition for kids of all ages. They were so popular that, during a 1945 newspaper delivery strike, New York City Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia took to the radio to read the comics so readers wouldn’t miss a week.

But while the Sunday funnies entertained, they also presented current events, voiced opinions and kept readers up to date on current events. And no one understood their power better than Jackie Ormes, a crusading columnist, humorist, artist and activist who used her pen as an instrument of protest and change in mid-twentieth century America.

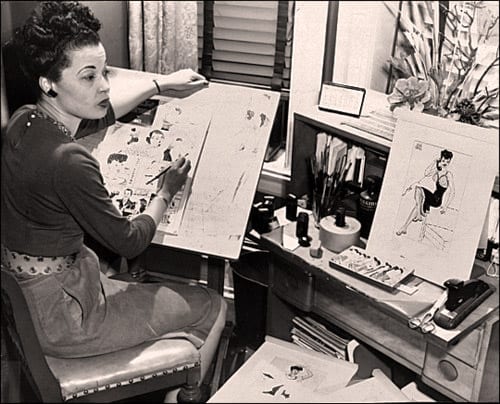

Highly-talented young artist

Born Zelda Mavin Jackson, she drew and wrote throughout her high school years in Monongahela, Pennsylvania. She was arts editor of her 1929-30 high school yearbook, which included her caricatures of teachers and students.

While still in high school, she began writing letters to the editor of the Pittsburgh Courier, a weekly African American Sunday newspaper. When, to her surprise, the editor replied, she snagged her first real writing assignment — covering a Joe Lewis heavyweight boxing match with the paper’s sports editor as her chaperone.

After graduating in 1930, she took a job at the Courier as a proofreader, editor and freelance writer, covering police beats, court cases and human interest pieces. But while she “enjoyed a great career running around town, looking into everything the law would allow and writing about it,” she really wanted to draw.

Torchy Brown character

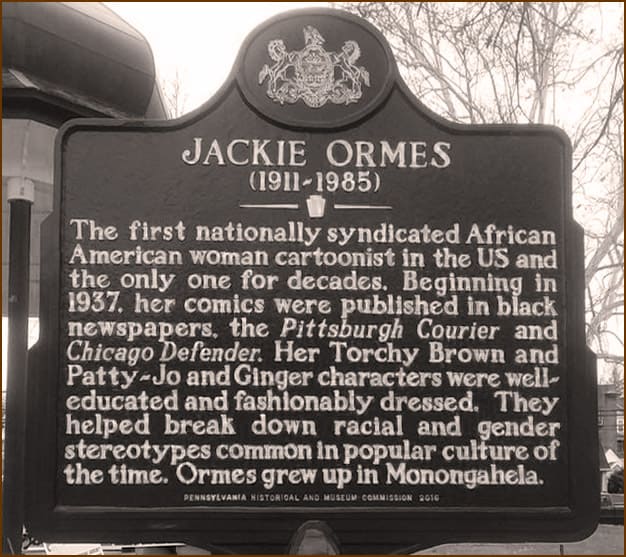

Ormes debuted her first comic strip, Torchy Brown in Dixie to Harlem, in the Pittsburgh Courier in 1937. And while her work wasn’t syndicated, the Courier ran her strip in all 14 of their city editions, giving her coast-to-coast readership.

Torchy Brown was a plucky, star-struck Mississippi teen who found fame and fortune performing at Harlem’s Cotton Club, her journey north mirroring the Great Migration of so many African Americans. With Torchy, Ormes made history by becoming the first African American woman to produce a nationally-published comic strip. It ran until 1940, before coming to an end when Ormes moved with her husband to be closer to his family in Ohio.

But she was unhappy there, leading to the couple’s move to Chicago in 1942, where Ormes soon took her place in African American society, writing a column for the Chicago Defender, one of America’s foremost black papers. After the end of World War II, her single-panel cartoon, Candy — about a smart, wisecracking housemaid, debuted in the paper, but ran for just four months.

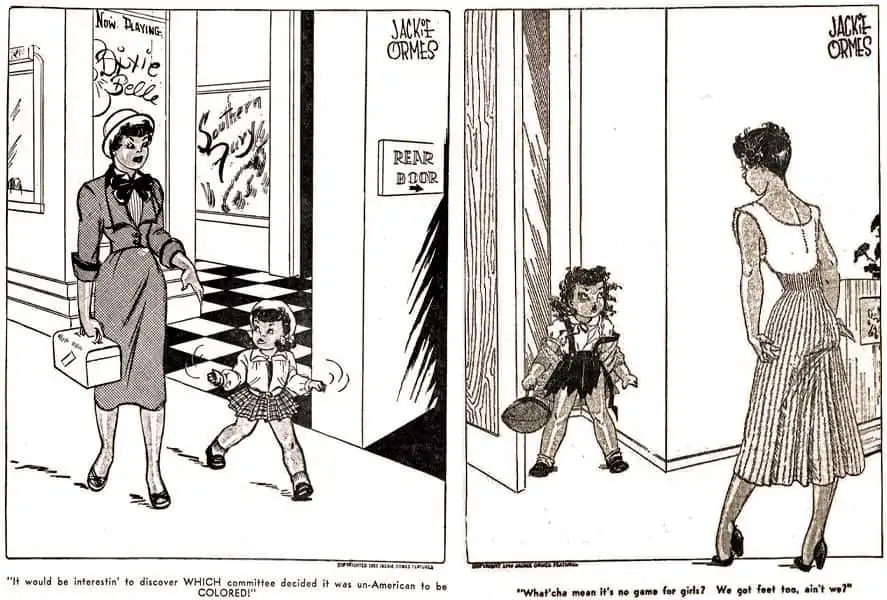

By August of that year, Ormes was back at her old stomping grounds, the Pittsburgh Courier, where she launched Patty-Jo ‘n’ Ginger, a single-panel cartoon read by millions during its 11-year run. Its big sister-little sister theme featured Patty Jo, a precocious, politically aware child who voiced opinions on everything from sexism and racism to McCarthyism, and her big sister, Ginger, a gorgeous black woman and fashion plate Ormes often depicted in pinup-girl poses.

Targeted by FBI

Ormes eventually caught the eye of the FBI when she appeared at a bookstore where several Communists were believed to have spoken. She worked during the Joe McCarthy era, a time rife with suspicion and paranoia. Yet not one of the 287 pages the FBI compiled on Ormes even mentioned her pioneering comic strips. Deborah Whaley, author of Black Women in Sequence ,writes they “ran a file on Ormes between 1948 to 1958. They would track her steps, following her to bookstores and other places to gather information on her possible connections to the Communist Party, even interviewing her several times.” Her file eventually ran to 287 pages — 150 more than the Brooklyn Dodgers’ Jackie Robinson.

Patty Jo, who publicly voiced what readers could only think, was so popular that, in 1947, Ormes contracted with the Terri Lee doll company to produce a doll based on her cartoon character. The Patty-Jo doll, in stores for Christmas that year, was the first American black doll with an extensive upscale wardrobe. She also represented a real child in contrast to black dolls of the time, which were mammy or Topsy dolls. Though they sold by the thousands to both black and white children, in 1949 Terri Lee opted not to renew Ormes’ contract and ended production. Today, original Patty-Jo dolls are highly sought after by collectors.

Torchy in Heartbeats

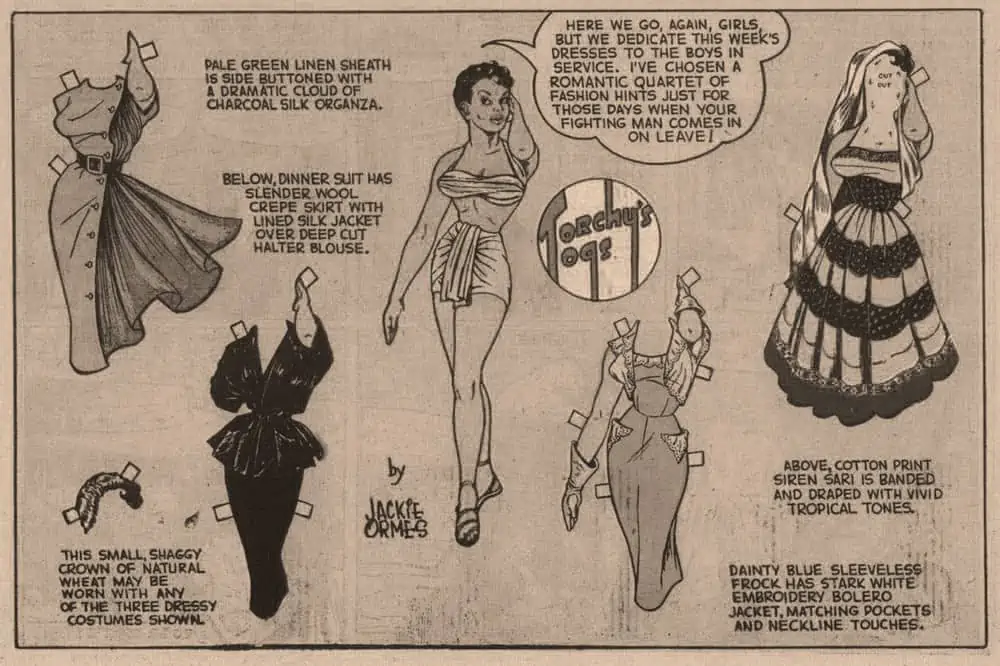

When, in 1950, the Courier launched an eight-page, full-color comics insert, a national syndicate urged Ormes to reinvent her Torchy Brown character for a new strip called Torchy in Heartbeats. All grown up since her debut in 1937, Torchy re-emerged as a beautiful woman with a flair for fashion who found herself in one adventure after another while seeking true love as she battled racism and society’s ills.

Torchy in Heartbeats also gave Ormes the opportunity to show her talent for fashion design and her vision of a beautiful black female body with a small secondary strip she called Torchy Togs. It featured Torchy as what readers of a certain age remember as a paper doll, with a fabulous wardrobe. One 1952 strip shows Torchy in a pinup pose alongside a “wonderful waist-nipped, breeze-whipped gown in pale green percale.” Readers followed Torchy’s love life through 1954, when newspapers began paring their comics sections to give more space to America’s Civil Rights Movement, which had gained momentum with the Supreme Court’s decision on Brown v. Board of Education.

Jackie Ormes retired in 1956, and focused her talents on creating murals, portraits and still lifes until advancing rheumatoid arthritis forced her to put down her pens and brushes. Her husband managed the historic DuSable Hotel in Chicago’s South Side. And as a member of Chicago’s black elite, Ormes rubbed elbows with leading political figures and entertainers who passed through the city and stayed at the hotel. She advocated for the South Side Community Art Center and served on the board of directors of the DuSable Museum of African American History. She also presided over the Urbanaides — a female auxiliary of the Chicago Urban League.

Growing recognition

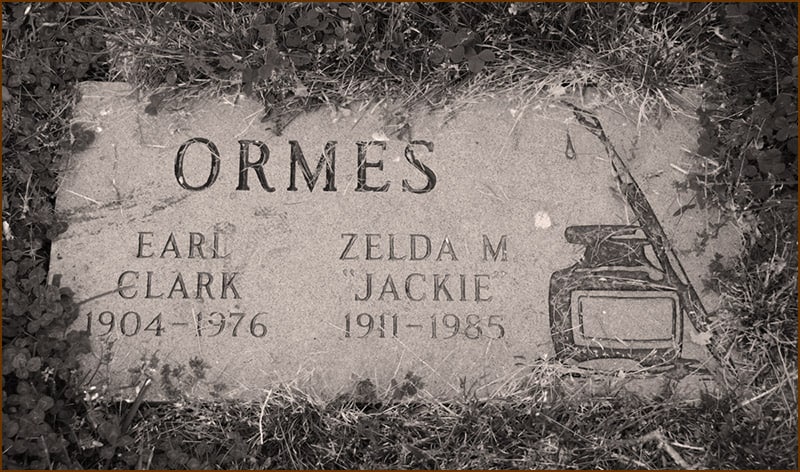

Jackie Ormes died of a cerebral hemorrhage in Chicago one day after Christmas in 1985 at age 74, and was laid to rest next to her husband in Hope Cemetery in Salem, Ohio. But it’s only been recently that this self-taught artist’s groundbreaking work has gained the recognition it deserves.

In 2014 she was posthumously inducted into the National Association of Black Journalists Hall of Fame, and into the Will Eisner Comic Industry Award Hall of Fame as a Judges’ Choice in 2018. A Google Doodle on September 1, 2020, honored her work. And, in 2016, a historical marker was dedicated to her next to the gazebo at Chess Park, one of Monongahela’s main community attractions.

In 2008, Nancy Goldstein’s biography of the cartoonist, Jackie Ormes: The First African American Woman Cartoonist, was published by the University of Michigan Press. In an NPR interview, Goldstein stressed the importance of Ormes’ positive representation of black women and girls at a crucial time in history. Late in her life, Ormes told an interviewer, “I have never liked dreamy little women who can’t hold their own.” Not only did her characters and creations defy expectations for black women; they gave readers strong models for what the next powerful generation of young black women could become.

Cartoon industry now

But ironically, Ormes’ own industry still remains, with few exceptions, off limits to them. From 1989 to 2005 there was only one nationally syndicated black woman newspaper cartoonist — Barbara Brandon-Croft, who cites Ormes as her inspiration. She knows how far ahead of her time Ormes was; as the first black woman to create a syndicated daily strip for mainstream papers, Brandon-Croft’s own Where I’m Coming From strip didn’t appear until 1989.

Today, the Jackie Mavin Ormes archive is housed at the DuSable Museum of African American History. There you’ll find original drawings, personal artwork, published cartoons, poems, and copies of “Social Whirl,” her column in the Chicago Defender. Also included, correspondence about Patty-Jo doll production and sales, a letter from Paul Robeson (himself a target of McCarthyism), and an original sketch of the Patty-Jo T-shirt which Ormes designed and sold by mail in the 1970s.

A very talented and groundbreaking woman. What she had to endure in order to perfect her craft and to publicize her artwork in the face of prejudice and misunderstanding from the federal government. She is a relative to our family and my father was in the same town with cousin Jackie, as we knew her in the early 1940s in the city of Salem, Ohio. Cousin Earl was older than my father Howard Arthur Tibbs and we are all bonded by the family’s unique history in the Northeast Ohio and Western Pennsylvania region. After 26 months of work . Finally, the 117th Congress of the United States passed legislation and President Biden signed into law the US Post Office and federal facility in Salem, Ohio to be renamed for Howard Arthur Tibbs – USAAF. He served in the units of the Army air Forces that would later on be referred to as the “so-called Tuskegee airmen /air women. The ceremony will occur 19th of May, 2023 CE 1 PM EDT. I only wish that my parents could be there to receive this honoring and it is long overdue. From the nation and definitely the city of Salem and the region. Cousin Jackie, I am sure would approve.