Maybe it’s the decadence of a double-chocolate Milano. Or those buttery, melt-in-your-mouth Chessmen. Or the handful of Goldfish (“the snack that smiles back”) a harried mom throws into a Ziploc bag on the way out the door with her little ones. Pepperidge Farm has been America’s bakery for generations. But did you know it all started with a housewife, a sickly little boy and a stately tree on a Connecticut farm?

Margaret Fogarty grew up in Flushing, Queens, New York. After graduating as valedictorian of her high school, she found a job as bookkeeper with a brokerage firm in 1915. It was there she met and married a partner in the firm, Wall Street broker Henry Rudkin, in 1923.

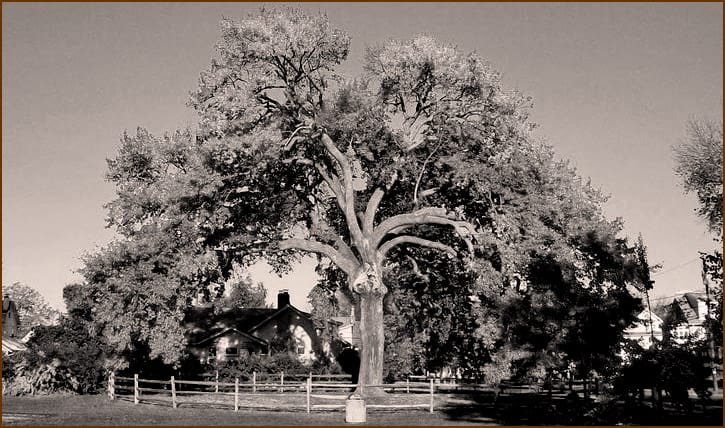

The couple lived an idyllic life on a 125-acre farm in Fairfield, Connecticut, named for the pepperidge trees growing on their property. He golfed and played polo; she showed horses, won ribbons, and cared for their three sons. Along with an English Tudor farmhouse, the property boasted a stable for 12 horses and a garage large enough for a fleet of cars.

Great Depression disaster

But the Great Depression, coupled with a serious accident in 1932 that left Henry Rudkin unable to work for six months, turned their perfect lives upside down. Margaret Rudkin, always practical and analytical, dismissed the servants, sold the horses and all but one car, and began selling apples from their 500-tree orchard, along with turkeys they raised on Pepperidge Farm, to help make ends meet.

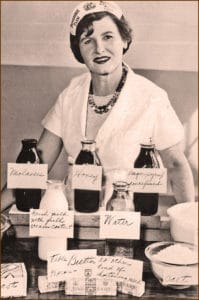

It wasn’t until her youngest son became ill with asthma and food allergies that Margaret Rudkin started baking. After an allergist suggested she steer clear of processed flour and refined sugars, she started researching wholesome, preservative-free foods, starting with her Irish grandmother’s whole-wheat bread recipe using stone-milled whole wheat flour, honey, molasses, sugar syrup, milk, cream and butter, and a coffee grinder from a local feed store to grind the wheat.

Quest for health bread

In 1937, at age 40, Rudkin produced her first loaf of “health bread.” But you know that saying, “if at first you don’t succeed?” Rudkin described her first try as something “that should have been sent to the Smithsonian Institution as a sample of bread from the Stone Age,” rock-hard and barely an inch high. Undeterred, she continued to experiment and, after discovering the wonder of yeast, settled on a vintage recipe that produced a tender, delicious loaf.

The bread seemed to improve her son’s symptoms. His allergist was so impressed he asked Rudkin to bake loaves for him and his other patients. Since the family was down to one car, Rudkin outfitted the garage as a bakery and, with one helper, began baking in small batches, using stone-ground wheat from an old mill on the Connecticut River, rescuing a set of baby-weighing scales from Rudkin’s attic, and gathering every mixing bowl and baking tin they could find.

25¢ a loaf

Rudkin took a basket of bread to Mercurio’s Market, a Fairfield treasure that, for more than 100 years, had provided quality foods and exceptional customer service. The grocer was skeptical when asked if he’d be willing to sell her bread. After all, not only was Rudkin inexperienced, she had the audacity to demand 25¢ for each loaf, enough to cover her costs, at a time when a white loaf sold for one thin dime. Then Rudkin sliced a loaf down and offered him a taste. Not only did he become a believer, taking every loaf she had brought into the store; but by the time she got home, he had left a phone message asking for more.

She next set her sights on the Manhattan market, turning out loaves of white bread from a vintage recipe using unbleached flour. By now, Henry Rudkin was back at work. Commuting into the city every day loaded down with two dozen loaves of bread, a porter met him at Grand Central Station and took the bread to Charles & Co., a specialty food store on 43rd Street. Before long, Charles & Co. upped their order to 1,200 loaves a week.

A push from Reader’s Digest

In the late 1930s, Rudkin spent $987 — a small fortune at the time — on professional equipment. Her bookkeeper figured she’d need to bake almost 3,000 loaves of bread a week just to break even. A distribution plan was hatched with the purchase of Pepperidge Farm’s first truck and a full-time driver who started at $18 a week. Within a year, Margaret Rudkin’s bakery was turning out 4,000 loaves a week. At the same time, Reader’s Digest discovered the brand, writing, “this home-baked bread industry has presented the local community with a thriving business, 45 new jobs and an annual payroll in excess of $50,000” (over $900,000 in today’s currency).

Never one to blow her own horn, Rudkin attributed her success to “quality and timing.” With so much commercially-produced, puffy white bread available, and fewer women baking bread at home, there was nothing like her loaves on grocery shelves. As the company grew, adding whole wheat and pumpernickel bread, along with dinner rolls, to their line, Rudkin needed more space. So the bakery moved into a former Packard automobile showroom and took over an unused hospital building. Within a decade, Pepperidge Farm was turning out 40,000 loaves an hour in a specially designed production plant in Norwalk, Connecticut.

World War II rationing

With World War II and its system of rationing, Pepperidge Farm’s special ingredients — Grade A butter, fresh eggs, fresh whole milk, unsulphured molasses and dark, sweet honey — were harder to come by. Rudkin had a choice. She could either lower the quality of her bread to meet the wartime demand for rationing, or she could limit production. She chose quality over quantity. While her bakers scraped the bottom of their flour bins, Margaret Rudkin learned how to substitute so quality never suffered. For every pound of butter the bakery had to cut from a recipe, it substituted 1/4 cup of heavy cream, since both had the same butterfat content.

After the war, the Rudkins sailed to Europe, where Margaret discovered cookies made by the company that supplied Belgium’s royal family. After somehow sweet-talking Delacre into allowing Pepperidge Farm to use its “secret” cookie recipes, Rudkin sent bakers to Belgium to train before importing a 150-foot cookie oven and bringing Belgian engineers and quality-control people to the U.S. to oversee production. By the end of 1955, Pepperidge Farm had introduced six new “distinctive” cookies to America, prompting Los Angeles Times food columnist Richard Sax to swoon: “Her insistence on high-quality ingredients was a breakthrough for American cookie lovers!”

Women’s advocate

But Margaret Rudkin was about more than just healthy breads and scrumptious cookies. After all, hers is the story of how one woman with no experience in the food industry founded a successful business at the height of the Great Depression.

Always a strong believer in working women, in the 1940s she offered advice for women who wanted to go into business while calling out the business world for not hiring women who clearly demonstrated their abilities in managing a home and family. Early in her career, she hired housewives, writing, “Look at what a bunch of women over 40 have done,” about the 125 women working in her bakery. “None of us had training or business experience. Most of us have children and home responsibilities. But we’re running this business and making it pay.”

Champion of women war workers

A wife and mother who understood women’s needs, she offered flexible hours. Unmarried local women preferred morning hours so they could do farm chores while the day was still young, while married women with children needed after-school shifts when older children could look after younger ones. She cited multi-tasking and everything housewives did as assets that prepared them to run a business: “Knowledge of how to buy well, use food properly, prevent waste, and maintain cleanliness, routine and system.” And when America’s women took to factory floors during World War II, Rudkin was their champion, telling the Edinburg Daily Courier in 1941: “I don’t believe there is any job women can’t do. They handle machines as well as men, and they’re marvelous to work with.”

Pepperidge Farm became known as a good place to work, with a benefit package that included six sick days per year, 10th-anniversary bonuses equal to four weeks’ wages, and safe-driving awards for truckers. And while it’s true Rudkin paid higher wages than most, and made it a point to hire women whenever she could, she was a product of her time when it came to equal pay for equal work: in 1961, a male mixer was hired at $2.15 an hour, while his female counterpart earned $1.75 for the same work.

“Outstanding achievement”

By the late 1950s, Henry Rudkin had taken over marketing and finances for Pepperidge Farm. But Margaret remained the company’s public face. In 1955 the Women’s International Exposition presented her with their “Award to Industry” for outstanding achievement. The next year, she was named one of the “Famous Seven” best-known female executives in America. And Fortune Magazine included her as one of its 50 most powerful businesswomen in the decade from 1950-1960.

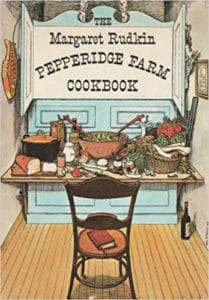

Margaret Rudkin sold Pepperidge Farm to the Campbell Soup Company, headquartered in Camden, New Jersey, for $28 million dollars (over $237 million in 2019 money) in 1961, becoming that company’s first female board member. Her Pepperidge Farm Cookbook, which included some 500 recipes, was released in 1963, becoming the first cookbook to find itself on the New York Times bestseller list.

1966 retirement

Margaret Fogarty Rudkin retired in 1966 and died of breast cancer the following year at Yale-New Haven Hospital at the age of 69. She is buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx, New York.

Her journey had taken her from being one of the “ladies who lunch” to a resourceful housewife and mother concerned for her child’s health to, finally, a smart, savvy businesswoman when successful female business leaders were hard to find. In her own words, “there isn’t a worthwhile thing in the world that can’t be accomplished with good hard work. You’ve got to want something first and then go after it with all your heart and soul.”

When I was a child, Pepperidge Farm Products were delivered to your home in Dutchess County, NY

Margaret’s story was just on the Food That Built America on the History Channel. What a brilliant business woman, right up there with Emily Post!