She is the only champion of women’s rights in the last two centuries to have both a crater on the moon and an asteroid named in her honor. Maria Mitchell was a star of 19th century American science who used astronomy to expand the boundaries of what women could expect and achieve. Her life and work are a root of the Science, Technology, Engineering and Math (STEM) movement that today draws ever larger numbers of young women to scientific careers. But, ironically, Mitchell is not well know to most of them.

When it comes to celestial bodies, they know Halley’s comet is famous for returning to our skies about every 75 years. And they may remember Hale-Bopp for 39 cult members who ended their lives in 1997 hoping to hitch a ride into space as it blazed across the sky. But they don’t know about “Miss Mitchell’s Comet,” discovered in 1847 by America’s first female professional astronomer.

Of whales and stars

Maria (pronounced: Ma-rye-a) Mitchell was one of 10 children born to a Quaker family in 1818 on the whaling island of Nantucket. In the Quaker tradition of gender equality, her father –a teacher and amateur astrologer with a telescope on their roof and contacts at Harvard’s observatory in Cambridge, Massachusetts — always encouraged her to pursue an education that didn’t skimp on science.

She was a quiet girl whose love of astronomy grew out of watching the skies with her father and learning to chart the placement of the sun, moon and stars as a child. By age 12, she had helped him calculate the position of their home on Nantucket by observing a solar eclipse. Two years later, experienced whalers who steered their ships by movement of the stars trusted her to do their navigational calculations.

Miss Mitchell’s comet

In the 19th century, observing the heavens was known as “sweeping the sky.” Astronomy was seen as a feminine activity and “ladylike avocation” rather than a serious job. But that changed in the 1870s when the field became professionalized, people began to be paid for sweeping the skies, and women found themselves with fewer opportunities.

While comets were nothing new in the first half of the century, discovering new ones was still a big deal — so much so that Denmark’s King Frederick VI, known as a patron of astronomy, began offering gold medal prizes in 1832 to anyone who found a new comet using a telescope.

And so it was that on the evening of October 1, 1847, Maria Mitchell was sweeping the sky with the telescope atop the Pacific National Bank where her father worked at the time when she saw what looked like a blurry streak, invisible to the naked eye but clear through the telescope’s lens. Thinking it might be a comet, she rushed to find her father and share the discovery, making careful notes of the comet’s position and continuing to observe to make sure it wasn’t a fluke. Two days later, Mr. Mitchell proudly wrote to Cambridge announcing his daughter’s discovery.

While she hadn’t been the only one watching the comet at about the same time, she was the only one who had carefully documented her observations in great detail. Her findings were published in the journal of Britain’s Royal Astronomical Society on November 12, 1847, giving her priority and legitimate claim to the gold medal awarded by the Danish king. The discovery of what became known as “Miss Mitchell’s Comet” catapulted her to instant fame and into the American Academy of Arts and Sciences — at age 30, she became its first female member and the only woman to be so honored until 1943.

Always shy and bookish, and known to avoid company whenever possible, she was unfazed by her newfound fame, writing in her diary, “One does enjoy acting the part of greatness for a while! But I was tired after three days of it and glad to take the cars and run away.”

Vassar professor

In 1865, Mitchell joined the faculty at newly-established Vassar College, becoming America’s first astronomy professor. She was also appointed director of the Vassar Observatory — the best-equipped observatory in the United States second only to Harvard — where she had a telescope made by Henry Fitz, America’s best maker of commercial telescopes before the Civil War.

Her annual salary was $800, a sum she took issue with after discovering it was just a fraction of what male professors earned. For Mitchell, gender equality was more than a Quaker tenet; it was something she grew up with on Nantucket, where whalers’ wives were left for months, if not years, to manage affairs while their husbands were at sea, fostering an atmosphere of independence and equality for women who called the island home. Never one to give up easily, Maria Mitchell fought hard for, and eventually won, her salary increase.

Dyestuff of the stars

Throughout her career, she made notable observations on sunspots, comets, nebulae, stars, solar eclipses and the moons of Jupiter and Saturn. But instead of seeing the heavens from a dry, scientific standpoint, she never ceased to revel in their beauty. Eight years after her discovery, her journal records an evening spent marveling at the “tints of the different stars, so delicate in their variety ,” and thinking “what a pity our manufacturers aren’t able to steal the secret of dyestuffs from the stars.”

At Vassar, Mitchell mentored circles of brilliant female students with an annual tradition of “dome parties,” serving up science with equal portions of poetry readings and dishes of strawberries in sweet cream. Which was only fitting, since Mitchell’s view of science was “not all mathematics, or all logic, but is somewhat beauty and poetry.”

Women’s minds and women’s rights

She had long argued that higher education was crucial to the independence of a woman’s mind: “Until women throw off this reverence for [male] authority they will not develop. When they do this, when they come to truth through their investigations … their minds will work on and on, unfettered.” Co-founder with Elizabeth Cady Stanton of the Association for the Advancement of Women in 1873, she advocated for women’s rights in the belief that women’s minds were wasted spending their days sewing rather than pursuing intellectual matters. Or, as she put it, “better to be peering in the spectrograph than on the pattern of a dress.”

Field work

Though based at Vassar, Mitchell was known for her field work. She traveled to Italy in 1856 to use the Vatican’s observatory, only to discover women were not allowed because it was also a monastery. Rebuffed, she wrote in her journal, “If I had before been mildly desirous of visiting the observatory, I was now intensely anxious to do so.” Remember … Maria Mitchell did not give up easily. After two weeks, Vatican officials allowed her in — the first woman to set foot inside.

In 1873 she went to a Russian observatory just outside St. Petersburg. And five years later, in 1878, Mitchell led an all-female expedition of her best students to Denver, Colorado, to observe a solar eclipse, traveling almost 2,000 miles on the new transcontinental Pacific Railroad, camping and setting up their telescopes on the open plains with awe-inspiring views of the Rocky Mountains.

Death and legacy

Maria Mitchell observed and studied celestial bodies and eclipses for more than 50 years. Before retiring after 28 years spent at Vassar College, she remembered gazing at the heavens through that small telescope with her father on their rooftop in 1831 and, by 1885, being among her students in a beautifully equipped observatory, recalling, “both days were perfectly cold and clear.”

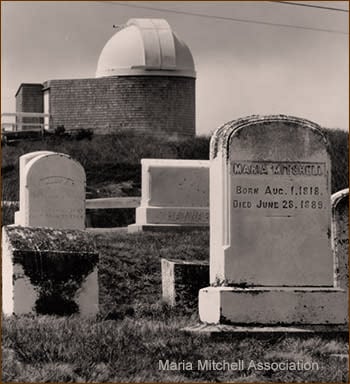

She retired in 1888 and died a year later in Lynn, Massachusetts, a telescope still at her window. Maria Mitchell was buried on the island of Nantucket, in Prospect Hill Cemetery, next to her mother and close to her father, in the shadow of the Maria Mitchell Observatory.

A crater on the moon is named for her, as is an asteroid discovered in 1937. Her archives are housed at Vassar. And the Henry Fitz telescope designed especially for her use is now part of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, though not currently on display.

A month after her death, the July 20, 1889, issue of Scientific American described Maria Mitchell with these words: “She stands out clear and conspicuous, like an evening star in the heavens she loved so well to study.”