For almost 100 years, this Wednesday’s Woman was the most recognized face in America. A savvy businesswoman, a shrewd marketer, and the self-declared Savior of Her Sex, she was Lydia Estes Pinkham who was to women’s health products what John Wanamaker was to department stores.

Pinkham was the tenth of a dozen children born to well-to-do Quaker parents in Lynn, Massachusetts. Educated at home, then at the Lynn Academy, she worked as a nurse, midwife and schoolteacher before marrying.

Marriage and financial ruin

In 1843 she met and married Isaac Pinkham. Jumping from one occupation to another, Pinkham dreamed big, but accomplished little. He thought he finally hit on something when he invested family money to set himself up as a builder — but his timing couldn’t have been worse. When the economic Panic of 1873 hit, Pinkham lost everything. When the stress of being sued for the inability to pay his debts broke him, leaving him unable to work, the four Pinkham children put their dreams aside to find work to help keep the family afloat. By 1875 they were almost destitute.

In the meantime, Lydia Pinkham had become a follower of something called the Thomsonian Botanical Movement, advocating self-help when it came to health care. At a time when long-established, trusted healers like midwives and herbalists were being replaced by newly-minted “regular doctors” from fancy medical schools whose treatments were just as likely to kill as cure, almost one-third of Americans favored Samuel Thomson’s use of herbal teas and botanical remedies to cure what ailed them.

Home-brewed remedy

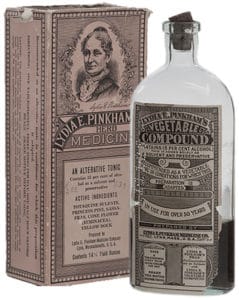

By 1875, Pinkham had been concocting a home remedy made of wild roots and herbs “preserved” with 18-19% alcohol for about 10 years, giving it to friends and family for female problems ranging from menstrual cramps and irregular periods to miscarriage to menopausal depression, hot flashes, and even uterine prolapse.

In making her tonic, Pinkham studied medical guides, the botanical books by Samuel Thomson, and herbalist John King’s encyclopedic American Dispensatory. King’s descriptions of the ingredients in each botanical remedy, their therapeutic uses and actions would one day lead to today’s U.S. Pharmacopeia and National Formulary.

The patent and the sales pitch

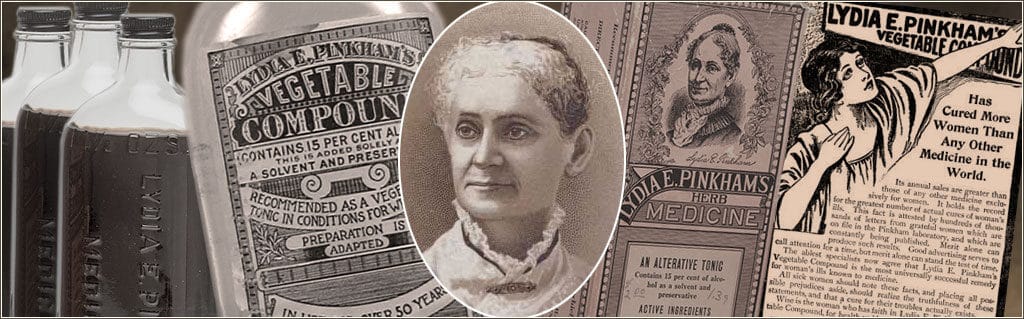

By 1876, demand for Pinkham’s herbal medicine had grown to the point that she shifted her manufactory from kitchen to basement, where her children bottled and packaged her remedy for sale as Isaac folded instructional pamphlets and leaflets. That same year, she founded the Lydia E. Pinkham Medicine Company to market her medicine and patented her remedy, ensuring the Pinkham family would control its formula for the next 50 years.

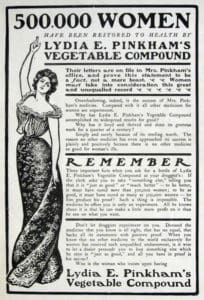

Advertisements for Lydia E. Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound ran in newspapers and popular magazines nationwide. One of the first women to write her own ad copy, today she is considered the Grandmother of Modern Advertising. Her company was also the first to use a woman’s face on its label in a brilliant marketing strategy — here was the compassionate, grandmotherly image of a woman who understood the discomforts of both menstruation and menopause. Ads even suggested her tonic could lower the risk of miscarriage, with consumer testimonials touting, “There’s a baby in every bottle,” which promptly became a product tagline.

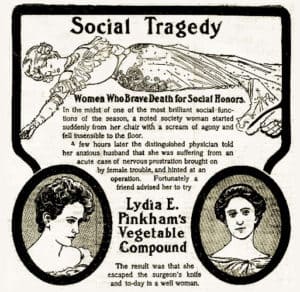

“Pain and suffering ads”

Pinkham also became expert in producing “pain and suffering ads” that would be right at home in publications like today’s National Enquirer. Each ad had a sensational angle — like the clergyman killed by a wife plagued by female complaints. The take-away from the ads was that tragedies like these could have been prevented if only the poor woman had taken Lydia E. Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound.

Seeing her compound as an alternative to the day’s standard medical treatment for women’s reproductive ills, Pinkham also encouraged and carried on a robust correspondence with her audience. Her “Pinkham Pamphlets” answered women’s questions and provided commonsense medical advice about menstruation and menopause.

Pinkham’s Department of Advice even guaranteed women that no men would ever read their letters, offering them an outlet for questions and concerns that might be too embarrassing or uncomfortable. Lydia E. Pinkham was, in her own way, informing and educating her female audience about their bodies and reproductive processes almost 100 years before the Boston Women’s Health Collaborative published its revolutionary Our Bodies, Ourselves in 1969.

From kitchen sink to multinational conglomerate

In May of 1883, Lydia Estes Pinkham died of a stroke at age 64 in the town where she was born — Lynn, Massachusetts. By then, her company was annually grossing $300,000 (or a sum equivalent to $7 million in 2017 dollars) .

Sales of her tonic peaked at $3 million in 1925 (about $41 million in 2017 dollars). But it went into slow decline in the face of a perfect storm of family arguments over its operation, the downturn of the Great Depression, and federal regulations like the Food and Drug Act that promoted truth in advertising.

In the late 1960s, the Lydia E. Pinkham Medicine Company was sold to Cooper Laboratories in California. Today, pills and liquid medicines based on Lydia E. Pinkham’s original recipe — without the alcohol — are available in pharmacies and online.

The Pinkham home was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2012. Today it is a designated site on the Salem Women’s Heritage Trail.

Misogyny then and now

Lydia E. Pinkham’s likeness appeared on her product labels; in advertisements; on lithographs and trade cards; and on souvenir plates and gift items — today all highly-prized medical collectibles.

But then, as now, when a woman’s face goes public, men are quick to voice their opinions. This letter, from a male critic in the 19th century, might be right at home on Facebook or Instagram today:

“Madam, Is it is necessary that you should parade your portrait in every country paper in the United States can’t you in mercy to the nation have a new one taken once in a while? Do your hair a little differently say — have a different turn to your head & look solemn. Anything to get rid of that cast iron smile! You ought to feel solemn any way that your face pervades the mind of the nation like a nightmare.”

~ ~ ~

The Original Lydia E. Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound Recipe

Unicorn root (Aletris farinosa L.) 8 oz

Life root (Senecio aureus L.) 6 oz.

Black cohosh (Cimicifuga racemosa (L.) Nutt.) 6 oz.

Pleurisy root (Asclepias tuberosa L.) 6 oz.

Fenugreek seed (Trigonella foenum-graecum L.) 12 oz.

Alcohol (18-19%) to make 100 pints

In Lydia E. Pinkham’s era, medical malpractice was rife, and phony, oft times dangerous to deadly concoctions tagged medicinal abounded. However, it must be said that Lydia’s Vegetable Compound, although containing 18-19% alcohol, was prepared with proportional preciseness and conscientious, insofar

as herbs proven to have some beneficiary affects pertaining to menstrual cramps

and related issues.

Though being a male, if I were a women

in the late 1800’s, merely being able to write a letter to Lydia as receiving her advised response, would be the equivalent of writing to the famous ‘Dear Abby’ column of more modern times.

Of course the famous compound’s advertisements were imaginatively stretched to medical limits in garnering sales. Yet, in many ways advertising has always been sprinkled with some form of utopian sunshine. 😉