When Crowns: Portraits of Black Women in Church Hats, by Michael Cunningham and Craig Marberry was published in 2000, it honored a tradition deeply rooted in African American culture. One that poet Maya Angelou simply called, in her foreword to that book, THE HAT. And for Mildred Blount, THE HAT was always about more than just headwear.

Hats would be a way for her to make her mark on the world in her own way, with dignity and elegance, one hat at a time. And she succeeded — in her day, she was trumpeted as “famous,” “internationally known” and “a leader in her field.”

Blount took her first steps toward a career as a hat maker in New York City in the 1920s. Orphaned at age two, she grew up knowing she had to work hard to provide for herself. She earned her high school diploma by taking evening classes after working full days as an errand girl at Madame Clair’s Dress & Hat Shop. It was there she discovered her love of, and talent for, millinery.

It didn’t take long for others to notice that talent. At 17, and without a lick of formal training, she was commissioned to make bridesmaids’ headpieces for the society wedding of Madam C. J. Walker’s granddaughter. Walker, the first Black female self-made millionaire, adhered to a policy of race patronage. As Lester Walton, the New York World’s only Black columnist reported, all the outfits worn by the bride, matron of honor, bridesmaids and flower girl were designed and made by Black designers. No fewer than 9,000 invitations went out. The New York Times, covering the wedding in a 1923 article, specifically described “coronets of braided silver cloth designed and made by Miss Mildred Blount.”

Interned at Famed Millinery Salon

In the 1930s, Blount applied for a job at the famous John-Frederics millinery salon (later known as Mr. John). One of New York City’s most fashion-forward establishments, it was considered the royalty of American hatters. After all, John-Frederics designed for some of the world’s most notable women. So as Ebony Magazine reported in a 1946 story, “it took courage for [Blount] to ring the bell in answer to their ad for a learner. … No Negro had ever applied before. Yes, she assured them, she had talent. All she asked for was a chance. P.S. — She got the job.”

Blount continued to hone her skills at The Cooper Union School of Art. A unique institution, it was free for the working classes, welcomed students of both sexes, and had no color bar. Plus, history, theory and criticism in the visual arts was an essential part of their curriculum — a perfect fit for Blount, who loved researching hat history, often pulling from the past for inspiration.

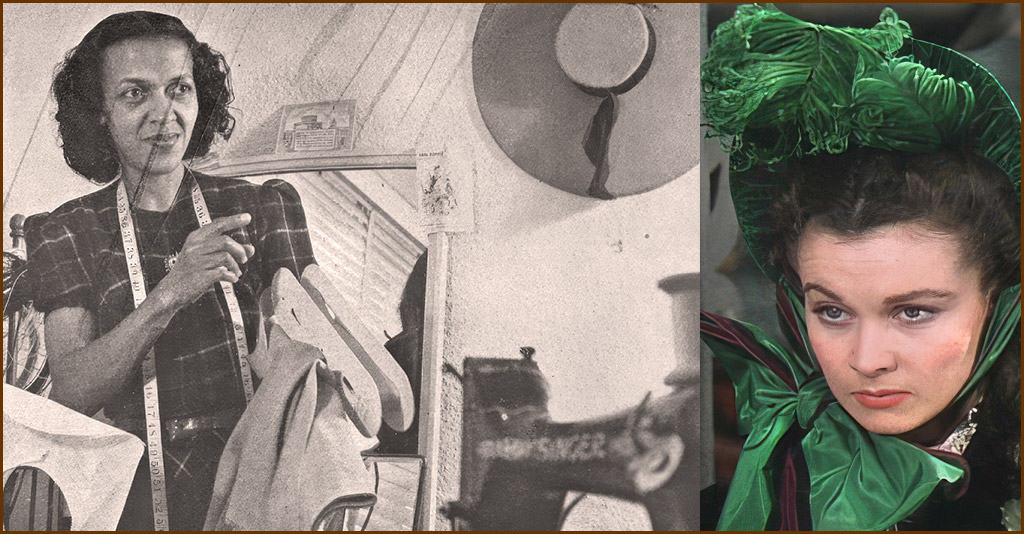

Her big break came when she was asked to do something small … as in miniature hats. Asked to create a collection of tiny hats for the 1939 New York World’s Fair, Blount created 87 miniature period hats that examined changing styles from the 17th through the 19th centuries. Her exhibit was extremely popular, attracting the attention of Mrs. David Selznick. Selznick was the producer, screenwriter, and film studio executive who produced “Gone with the Wind” and “Rebecca,” earning him two Oscars for his work. In 1939, he tapped John-Frederics to create the hats for “Gone with the Wind.”

Documents from Selznick’s archives reveal he adamantly refused to grant screen credit to John-Frederics who, despite making several cross-country train trips to Los Angeles, couldn’t complete his work on Scarlett’s hats. He agreed the remainder would be made at his New York studio — where it’s quite likely Blount had a hand in choosing materials and creating hats for the film’s “Honeymoon” sequences. As anyone who has ever seen the film will tell you, she carried out her task spectacularly. Yet Blount received neither film credit nor any public recognition for her work.

Denied Credit for Hollywood Hats

Mildred Blount stayed with John-Frederics for 13 years, steadily gaining experience while creating hats for some of the biggest stars and socialites of the day. Though she was anonymous when the credits for “Gone with the Wind” rolled, she didn’t stay that way for long. Blount was promoted to Senior Hat Designer at Frederics and sent to Los Angeles to head up his Beverly Hills salon. It was there she had the opportunity to design for and work with actress Joan Crawford as well as renowned dancer, choreographer, author, anthropologist and social activist Katherine Dunham.

She was also commissioned to create the wedding cap, sunburst starched-tulle ruffle, and veil for the 1941 wedding of society heiress Gloria Vanderbilt. Famously refusing to work with anyone refused to treat her as an equal, Ebony Magazine, covering the Vanderbilt wedding, described Blount as “an honored guest at many society weddings [who] has always refused the mock humility of the back-door entrance.” A year later, one of Blount’s wide-brimmed, sassy summer “pancake” hats made the August 1942 cover of Ladies Home Journal, with its circulation of over a million readers.

Still determined to make her own name in the world of millinery, Blount resigned from John-Frederics in 1943 after winning a Rosenwald Fellowship. Its grant of $1,800 for professional development allowed her to open her own Beverly Hills shop in 1945, serving private clients while building her reputation as “milliner of the stars” with celebrities like Marlene Dietrich, Ginger Rogers, Mary Pickford, Rosalind Russell, and classical singer/contralto Marian Anderson.

She also developed custom fabrics and colors, along with innovative stiffening and dyeing techniques that turned linen into shimmering straw-like creations. Some of her hats, sold with matching gloves and scarves, even had detachable and reversible brims. She once remarked, “my desire to do this work is first of all to acquaint all who see it with the hidden possibilities of women.”

Judy Garland and Fred Astaire

All this while still working — uncredited — for Hollywood’s motion picture industry, including having designed hats for Judy Garland in the 1948 film “Easter Parade” starring Garland and Fred Astaire. Then, in 1954, Jet reported in its “New York Beat” column that “Mildred Blount, the Los Angeles designer, will get screen credits in Columbia’s “Joseph and His Brethren. She created the Egyptian headdresses worn by the actors.” Unfortunately, the film was shelved when director Frank Capra left the project after Columbia had spent roughly $1 million on the Biblical drama.

But a year later, in 1955, Mildred Blount was officially inducted into the Motion Picture Costumers’ Union, becoming the first African American to join the AFL affiliate. Her membership meant she could finally create costumes for Hollywood films under her own label. It also provided her a platform from which she could advocate and fight for the inclusion of Black artists in the film industry.

Blount Hats in Museum Collections

Mildred Blount reportedly died in Los Angeles in 1974. It’s said she continued to work right up until that time. Today her hats and headpieces can be seen in the collections of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) and the California African American Museum (CAAM). But her considerable legacy lives on.

In 2019, Ruth E. Carter won an Academy Award for costume design on the 2018 global smash hit “Black Panther.” Two years later, she became the first Black and only the second costume designer ever (the legendary Edith Head being the first) to receive a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. And in recognition of the shoulders on which she stands, Carter recently started the Mildred Blount Scholarship Fund, honoring “the Black woman who did the millinery work in Gone with the Wind,” and who was the first African American member of the Motion Pictures Costumers Union.

What an incredibly talented woman. She is an inspiration to young and old. I am delighted to learn about her in my senior years. I know she was orphaned at a young age and I want to know of her personal life. Did she have extended family, children… a love life?

Thank you for this article.